Book Review: Radiohead鈥檚 Visual Legacy

The Ashmolean Museum鈥檚 catalogue features Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood鈥檚 collaborative artworks, offering insight into their 1990s origins

Michael Pearce / 黑料不打烊

26 Sep, 2025

This is What You Get, by Stanley Donwood, Thom Yorke, Lena Fritsch, Alex Farquharson, Nico Kos Earl, Benjamin Myers, Mark Radcliffe, published by the Ashmolean Museum

For three decades I have enjoyed a long and loving relationship with the rock band Radiohead’s brilliant 90s recordings OK Computer and The Bends, which were both works of purest musical genius. As an avid fan of these perfect records, I also wanted to love This is What You Get, the catalogue for the Ashmolean Museum’s exhibit of Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke’s collaborative paintings, drawings, sketches, and memorabilia of the band’s artistic impact, and opened the box delivering the review copy with some excitement. I remember admiring the cover art promoting both albums for its graphic clarity when they were released, and expected to enjoy the book, either for the nostalgic pleasure of temporarily escaping from the unpleasant present by revisiting a favorite band, or for the gratification of expanding my vague knowledge of the ciphered meanings of their enigmatic words and music.

But This is What You Get is so flimsy that it wrinkled overnight with the changing weather, becoming a slightly furrowed and curling embarrassment. Worse, the LP-sized book was too heavy for its thin covers and picking it up it felt like holding a dead fish as it bent, slid, and flopped from my fingers. First impressions matter. While very meta, clever, and sarcastic, the glib and passive-aggressive title did little to improve the limp impression the book had already made. The cover is a grim graveyard of gibbets, with gray and spectral figures haunting the corners, brightened by a fiery horizon behind silhouetted conifers. Opening the fragile book immediately creased it – cover and spine – predestining it for a grim future on the grubby shelves of a secondhand store. No. No. No.

I had read disparaging articles complaining about the Ashmolean show with some dismay, feeling defensive for the artists who were hectored for white-lining out of their respective lanes – especially singer Thom Yorke, the mellifluous shoegazer who had dared to pretend to be a painter, not a rock star, but his short preface does little to disperse such criticisms, as a flippant and dilettante confession muddling self-deprecation with self-congratulation.

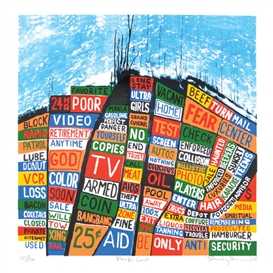

Curator Lena Fritsch provides a short introduction, then pages of unexplained imagery are spread in a stream mostly composed of forgettable collages of text and random, fuzzily degraded photos from the early days of 72dpi image file digital cameras that were used in brochures promoting the albums. As documents of the 90s they are refreshing reminders of the broken and millenarian mood of the decade, and the jewel-cased compact discs they once wrapped felt like a plastic-covered indictment of the end days, as much a celebration as they were frightening revelations of digital doom. We partied like it was 1999, then, and laughed skeptically in the jaded face of the death cults and disasters that were predictable signs of the apocalypse. The decade was decadent, and the mood was set for a season of deterioration – and artists amused us on the edge of the void with shock and offense as entertainment.

In Fritsch’s interview with Donwood and Yorke, which mostly covers their offhand use of degrading digital imagery, the reminiscing singer confesses to a fascination with videos made by a fellow Exeter student who repeatedly shot video and re-filmed it as it played it on a screen until the image became meaningless. “I was obsessed with filming the TV,” said Yorke. Their image-making was arbitrary and impulsive, the lurid mauve of the iron lung born of their ignorance of early versions of Photoshop – Donwood recalled, “we didn’t know about the difference between RGB and CMYK.” They ramble about smoking pot while they played with the program and about their self-conscious strategies to make images appear random, when they were anything but spontaneous.

This Promotional Book Was Endorsed by Tate Britain Curator Alex Farquharson

Tate Britain curator Alex Farquharson was an undergraduate with Donwood and Yorke in the English Literature and Fine Art course at Exeter University and provides historical context and a layer of art-world respectability, describing meeting them while they were students, and the pair’s first collaboration on covers for the song My Iron Lung, released as a single, and the album The Bends. They sneaked into the basement of an Oxford hospital to film a CPR mannequin, then re-photographed the grainy photo as it appeared on a television. At the time, some of the dystopian pictures were powerful images that resonated with the band’s alienated, disappointed, and angry Gen-X audience, who recognized the aesthetic lineage of punk appropriation, worn-out horror videos, and – if they were art students – anti-art.

But pitched in the fishy context of the floppy catalogue, which feels more like an expanded glossy magazine than a book, Donwood and Yorke’s imagery looks faded and inconsequential, as dated and toothless as Dada. Essays by Farquharson and James Putnam attempt to give them historical credibility, and Putnam pitches in with a detailed narrative about the history of album cover art, but the connections are thin and only emphasize their work’s fragile provenance, comparing their impulsive gestures with Storm Thorgerson’s brilliant photographic surrealism, or Roger Dean’s lyrical wonders. Donwood and Yorke scanned blobs of wax and turned the Photoshop controls up to 11.

What Does Cindy Sherman Mean in 2025?

Farquharson compares Donwood and Yorke’s The Bends album cover to Cindy Sherman’s untitled image of two mannequins kissing. What does Cindy Sherman mean in 2025? Everything in art has turned yellow since 9/11, since Donbas, since the murder of Charlie Kirk. Donwood and Yorke imitated Barbara Kruger by printing giant posters of the band’s lyrics and abstruse statements, deliberately mocking multi-millionaire John Lennon’s “War is Over” billboards with their superficial and ironic “Phew, for a minute there I lost myself.” Acting out arting, they scribbled doodles. They copied graffiti. They played Monopoly.

There are charming exceptions to the superficiality of most of the art. Donwood’s linocuts for Yorke’s solo album The Eraser are nice, but shallow, and certainly not canonically great art. His paintings for King of Limbs are pleasant modernist landscapes, but they feel a bit too much like hotel-room art framed behind wobbling plexiglass and screwed to a wall. The collaborative A Light for Attracting Attention and A Wall of Eyes is a gentle, if derivative, mashup of superficial decorative elements of Gustave Klimt and David Hockney in abstract mood.

Donwood and Yorke’s art reflected the meaningless felt by their generation, but that meaninglessness has not aged well. Yorke looks like he is frozen in time, a white haired sixty-year-old dressed in the fashions of a teenager worried about street-credibility, and his notebooks appear to be adolescent journals filled with a patchwork of scribbled lyrics documenting the desperate preoccupations of the era punctuated by amateurish drawings and clipped imagery, slogans snatched from advertising and self-help. Pages of text arranged in Instagram squares bow to the commercial needs of marketing and emphasize the full integration of their art into Guy Debord’s spectacle – flimsily masked by the false front of cynicism and irony bluntly embodied in the explicit slogan “You are a target market.”

I wanted to like this book, but this is what you get.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS