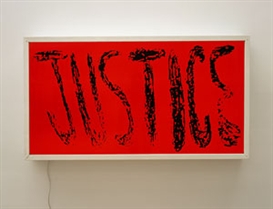

Alfredo Jaar, The Gift, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery (Johannesburg, Cape Town), Galerie Lelong (Paris, New York), Lia Rumma (Milan, Naples), kamel mennour (Paris), Galerie Thomas Schulte (Berlin).

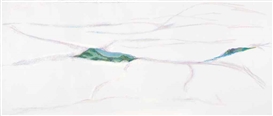

On the banks of the Rhine, lies one of the most spectacular locations in Basel, looking out towards the Old Town, beside a burial ground for Basel’s most distinguished and the quiet cloisters of the Münster cathedral — a place of quiet contemplation and spiritual seclusion. It is the perfect spot — as you quietly reflect on the course of time while gazing at the ripples of the river before you — for a moment of meditation. When you arrive at this extraordinary viewing point, below the Pflaz, you’ll find a temporary toilet. After all, where else nowadays can we truly retreat to concentrate on the internal world than the bog?

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Toilet on the River, 1996. Courtesy the artists and Sprovieri (London).

The installation--Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s The Toilet on the River (1996-2016)—is more than a metaphorical send-up, drawing its unavoidable analogy between spiritualism, nature and the processes of the physical body. As philosopher Slavoj Zizek says, a toilet can tell us a lot about the existential attitudes of a place: “In a traditional German toilet, the hole into which shit disappears after we flush is right at the front, so that shit is first laid out for us to sniff and inspect for traces of illness. In the typical French toilet, on the contrary, the hole is at the back, i.e. shit is supposed to disappear as quickly as possible. Finally, the American (Anglo-Saxon) toilet presents a synthesis, mediation between these opposites: the toilet basin is full of water, so that the shit floats in it, visible, but not to be inspected. [...] It is clear that none of these versions can be accounted for in purely utilitarian terms: each involves a certain ideological perception of how the subject should relate to excrement.” The Kabakov’s traveling toilet is one take on a theme, connecting 19 artworks that visitors to Art Basel can encounter next week, presented across the city’s historical centre, as part of Samuel Leuenberger’s Parcours. Leuenberger--director and curator of the not-for-profit SALTS in Birsfelden—has devised a ‘figurative’ stance for 2016 that is undeniably of the moment: How do humans relate to one another when their sense of purpose is shaken by the daily social, political and economic distress of the times in which we’re living? Beyond Parcours, the question proliferates among the artworks on display, while conversations on mass migration, race, and justice are also on the agenda at this year’s Salon program.

Ai Weiwei, Chandelier, 2015. Copper, crystal and light fixtures 400 x 241 x 231 cm. Courtesy of Galleria Continua, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana. Photo by: Oak Taylor-Smith.

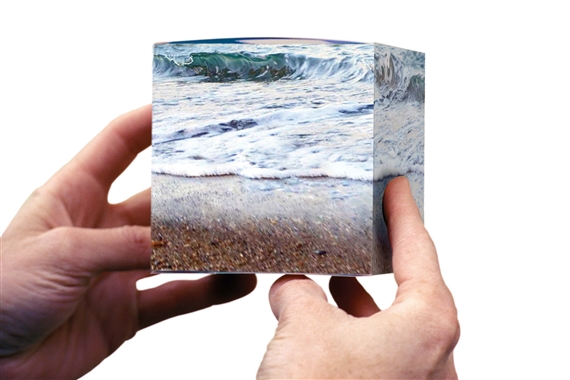

Tom Friedman, Untitled (White Bread), 2013. Styrofoam and paint 36 x 36 x 37/8 inches (91.4 x 91.4 x 9.8 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

An understanding of the things that are universally shared begins with a perspective on the local. Last June, Beijing’s Galleria Continua was the first to put up a solo exhibition by Ai Weiwei in China, shortly before the artist’s passport was returned. Weiwei’s exhibition was, the gallery said, ‘not political’. In the Galleries sector, a work from the exhibition, Chandelier (2015), inspired by the Han dynasty, will scintillate with crystals. It is indeed a subtler exploration of the tension between ancient and modern in his homeland than some of the activist artist’s other works, yet viewed in the context of Basel it’s hard to resist reading it as a comment on status, social order and the symbols of power and control. Beneath the glittering surface of Basel, imposing social order by controlling our sensory experience is further explored in the dank depths of the Birsigtunnel—a former sewage tunnel below the Grand Hotel Les Trois Rois. Part of Parcours, Chilean artist Iván Navarro—who grew up under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet--has suspended seven pairs of traffic lights from the ceiling, illuminating in green, yellow and red in turn, in a non-stop loop. Stripped out of their usual function, and installed to move like a child’s mobile, Navarro alludes to the way citizens unconsciously adhere to systems of control.

Sol Calero, Untitled (Facade 4), 2015.Acrylic, sand, canvas 200 x 290 cm. Courtesy Laura Bartlett Gallery, London.

Assimilation today is ambivalent. The ubiquitous everyday and its relationship to consciousness and perception in the urban environment is probed in a myriad of other forms at Basel this year. Riffing on these ideas with humour is American conceptual sculptor Tom Friedman, who is inspired by daily detritus, from pizzas and hamburgers to pencils and bubblegum. At the Luhring Augustine booth you will see (Untitled) White Bread (2013), a giant Styrofoam slice of bread that considers the common up close, revealing the miraculous and quasi-comic aspects of the overlooked, ever-present signifiers in western consumerist culture. Meanwhile in the Statements sector, the exoticisation of the internal architecture of the quotidian and the danger of outside narratives and unilateral identity construction are questioned by Sol Calero’s Casa de Cambio, presented by Laura Bartlett. For Calero, pan-continental identity is a pressing concern in contemporary culture, especially for artists emerging from Latin America, whose identity is still shaped according to markets and discourse that takes place predominantly in the West. Using Basel as a way to critique globalization as colonialism from the inside, Caracas-born Calero recreates a Venezuelan currency exchange. Local political and social complexities are often subsumed by the notion of a ‘Latin’ identity; Calero employs objects and items that resonate with the stereotypical idea of this identity, from wall coverings, furniture, exotic travel posters, and ceramics—as well as a monitor playing video works of other artists from the region—to challenge persistent ideas and their impact. The immersive Casa de Cambio speaks directly of the current crisis in her native country that has led to a drastic national food crisis, at a moment when the Venezuelan currency is on the brink of total collapse as economists predict imminent hyperinflation. Art does not offer a solution to the problems that we are facing, but it is a way to express the nuances we are often overlooked.

Sam Durant, Labyrinth, 2015. Courtesy Blum and Poe Gallery, Los Angeles, Sadie Coles HQ, London, and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steve Weinik for the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program.

Working with a similar method to shed light on stories that are often unheard, Sam Durant has built a 40 x 40 foot maze out of chain-linked fencing material on Münsterplatz. Durant invites visitors to wander through his Labyrinth (2015) in order to experience, fleetingly, the same feeling as the prisoners do at Graterford State Prison, near Philadelphia, who had helped develop the installation alongside Durant, together with participants in the Mural Arts’ Guild re-entry program, over the course of a year. Dealing with mass incarceration and the effect on both inmates and their families and communities on the outside, Durant’s engaging community-facing work was originally presented as part of The City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program’s Restorative Justice program, inviting the public to leave behind notes describing their experiences of incarceration in the walls of the labyrinth. In Basel, where the incarceration rate is only 84 per 100,000, the work’s meaning is significantly shifted, but the experience of immobility and the impact of psychological and physical boundaries and borders is an epidemic of our times. We cannot give in to fear of what lies beyond the walls: Acts of compassion and love, Durant reminds us, transcend them. We’re in this together.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS