JEAN CROTTI Inhabiting Abstraction

In April 1916, Jean Crotti (1878 ŌĆō 1958) was in an exhibition at the Montross Gallery, New York

John Yau / The Brooklyn Rail

01 Apr, 2011

FRANCIS M. NAUMANN FINE ART | MARCH 18 ŌĆō MAY 13, 2011

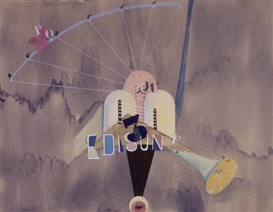

In April 1916, Jean Crotti (1878 ŌĆō 1958) was in an exhibition at the Montross Gallery, New York, along with Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, and Jean Metzinger. The newspaper dubbed them ŌĆ£The Four Musketeers.ŌĆØ According to Francis Naumann, who organized the exhibition and wrote two essays for its highly informative catalog, ŌĆ£Crotti got into a heated exchange with Gleizes, who thought that the titles Crotti had given to several paintings were too provocative.ŌĆØ Given that a gouache from the Montross exhibition has the word Dieu (God) written on it, it is likely that Gleizes, although a devout Catholic, didnŌĆÖt believe an expression of faith was suitable material for modern art. GleizesŌĆÖs sense of avant-garde correctness prevailed, of course, leaving Crotti and his workŌĆöfor a variety of reasonsŌĆönearly out of sight for almost a century.

Four years earlier, in 1912, Gleizes and Metzinger collaborated on a theoretical essay about Cubism, which, as their painting makes clear, they didnŌĆÖt understand. Despite being conventional artists and failed Cubists, their work is often included in exhibitions devoted to the early years of Cubism. Duchamp, who later became CrottiŌĆÖs brother-in-law, is forever linked with Dada and many a succ├®s de scandale including ŌĆ£Nude Descending a StaircaseŌĆØ (1912) and the ŌĆ£readymade,ŌĆØ a term he coined in 1915 to describe his use of found art. Although Crotti was associated with the Dada movement (1915ŌĆō1920), he seems to have never done anything scandalous or nihilistic. He and his wife, Suzanne Duchamp, started the short-lived movement Tabu Dada (1921ŌĆō22), an optimistic offshoot of Dada. Whereas the other three gained attention and notoriety in their lifetime, Crotti seems to have been barely noticed from the beginning.

In 1952, responding to a letter Crotti had written him regarding his almost complete obscurity, Duchamp made a number of observations worth citing:

Artists throughout the ages are like Monte Carlo gamblers and the blind lottery pulls some of them through and ruins others. To my mind, neither the winners nor the losers are worth bothering about. ItŌĆÖs a good business deal for the winner and a bad one for the loser. I do not believe in painting per se. A painting is made not by the artist but by those who look at it and grant it their favors. There is no outward sign explaining why a Fra Angelico and a Leonardo are equally ŌĆ£recognized.ŌĆØ It all takes place at the level of our old friend luck.

Duchamp goes on to say:

[Y]ou are certainly the victim of the ŌĆś├ēcole de Paris,ŌĆÖ a joke thatŌĆÖs lasted 60 years (the students awarding themselves prizes, in cash). In my view, the only salvation is in a kind of esotericism, yet, for 60 years, we have been watching a public exhibition of our balls and multiple erections.

Near the end of the letter, Duchamp states that CrottiŌĆÖs ŌĆ£originality is suicidal as it distances you from a ŌĆśclienteleŌĆÖ used to ŌĆścopies of copiers,ŌĆÖ often referred to as ŌĆśtradition.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

By DuchampŌĆÖs standard, Crotti should have received at least some attention for his ŌĆ£esotericism.ŌĆØ Clearly, ŌĆ£[o]ld friend luckŌĆØ felt otherwise. The primary reason his work has been repeatedly overlooked is because he never developed a signature style, which, in fact, he resisted doing. Crotti shares this with Serge Charchoune (1888ŌĆō1975), who was friends with Man Ray and Duchamp in Paris and associated with the Dadaists until 1925, when he broke away from the group. Art historians and others in the categorizing business have never found a suitable pigeonhole for either Crotti or Charchoune. And yet this is the very reason why I think it is an opportune moment to look at CrottiŌĆÖs work. It seems to me that the artists who learned from various avant-garde developments, but never assimilated into them, are the ones younger artists can learn from today, just as Peter Acheson, Chris Martin, Andrew Masullo, Norbert Schwontowski, and others learned from Forrest Bess (1911ŌĆō1977) in the 1980s.

The exhibition begins with a modestly scaled abstract painting, ŌĆ£Paysage Synth├®tiqueŌĆØ dated 1911, making it contemporary with Wassily KandinskyŌĆÖs first abstract paintings (1911ŌĆō1914). Important examples from every significant phase and development in the realm of abstraction that Crotti explored are included in the show, from the paintings he did in the early 1920s inspired by the kaleidescope, to the cosmic abstractions from the Tabu period, to his last, inspired paintings from the 1950s. Like other early abstractionists, Crotti was preoccupied with the infinite, which he equated with God. When addressing this preoccupation in text, he chose to write about himself in the third person: ŌĆ£[He] seemed to be an instrument of God, given the responsibility of transmitting messages to man.ŌĆØ

One isnŌĆÖt sure what message Crotti believed he was trying to deliver. To add to the confusion, his oeuvre is rife with one-of-a-kind works. One gem is ŌĆ£Parterre de reveŌĆØ (1920), in which he framed his painting palette and then signed it. It is a readymade that could pass for a 1950s Abstract Expressionist painting done by an unknown but intriguing artist. Like Bess, Crotti believed that he was a conduit. His strongest, most affecting paintings deal with the theme of the birth (and implied death) of planets and other celestial orbs. In ŌĆ£NocturneŌĆØ (1922), which was made during CrottiŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Tabu DadaŌĆØ period, the artist depicts three large, overlapping spheres, which have been cropped by the paintingŌĆÖs actual edges. They are red, medium brown, and dark brown. Smaller black circles and a white circle combined with black and green sections activate the monochromatic planets. ItŌĆÖs as if we are looking at unknown planets from a spaceship.

The birth and death of the universe was one of CrottiŌĆÖs recurring preoccupations, which helps explain his interest in kaleidoscopes, their shattering and reconfiguring of planes of light. His use of spirals, which began around 1920, preceded DuchampŌĆÖs rotoreliefs, as well

as anticipated the discovery of black holes in the universe. Done near the end of his life, ŌĆ£D├®sagr├®gationŌĆØ (1955) consists of three spiraling circles, both emerging from and disintegrating into paint. While he never pursued a style, his belief that art was ŌĆ£the subconscious act of translating the feeling of the InfiniteŌĆØ led him into a domain all his own.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS