Love, Rebirth, and the Magic of Dolores Chiappone

The story of Dolores Chiappone’s turbulent life, who turned suffering into art through self-made magic

Michael Pearce / ���ϲ�����

29 Oct, 2025

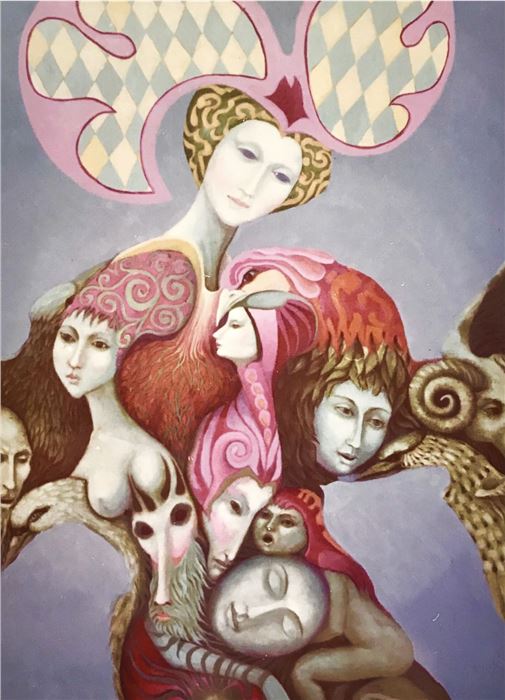

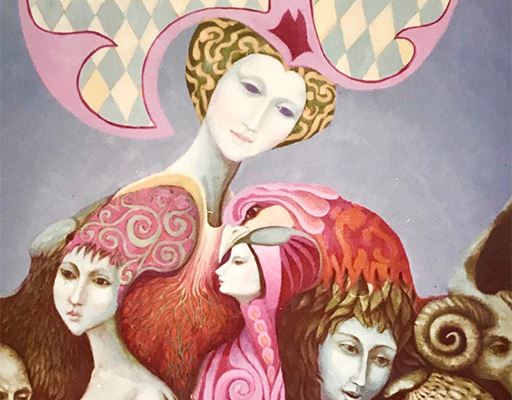

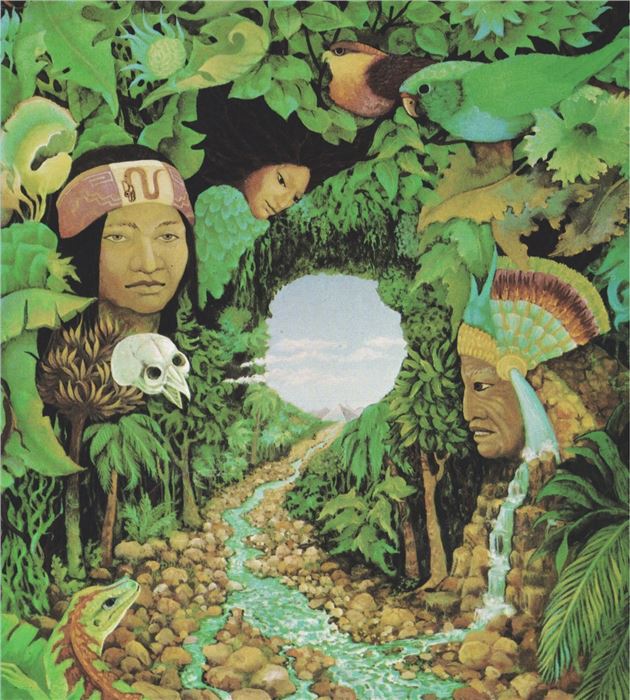

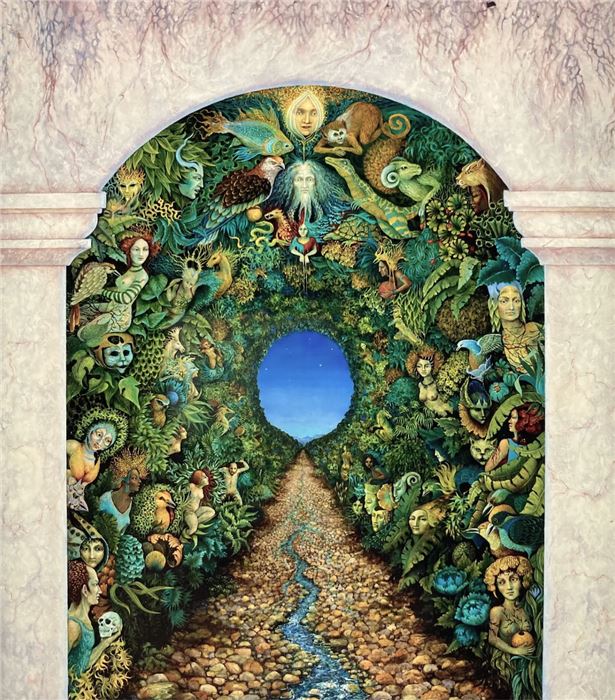

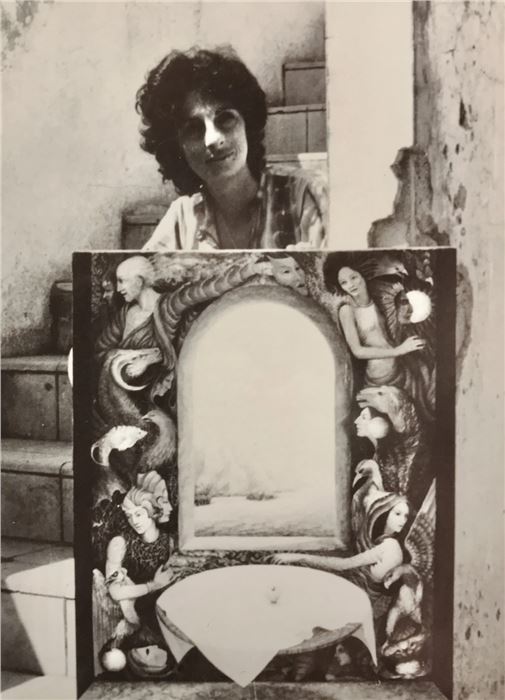

Dolores Chiappone in Mexico c. 1968 with her painting Party in the Walls

It is not fashionable in this cruel time to speak of love, or sensuality, or fragility regarding paintings. It is, in fact, the mark of a fool to write about art that fills the heart, that makes the viewer feel the harmony of their own inner voice mingling with the melody of the image’s song, or to attempt to sense the language and lyric of the artist’s soul. This account is a love story set in the sense and pleasure of Dolores Chiappone’s fragile but fierce magic and her fertile palace of memory and manifestation. Her paintings match the extraordinary stories she told of her century of experiences – rich and vivid, mysterious, with a hint of threat and abundant love for the vibrant life she saw thriving in everything. They are the visual equivalent of the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, wondrous paintings of a place where life and death are equally luxurious and tragic, and chromatic experiences occur in a kaleidoscopic flood of imagery, richly delivered, and subtly composed.

Many of them are her magical projections into the future, envisioning beautiful manifestations of her hopes and desires. She often painted herself into them, fearlessly opening herself to the world as a survivor of some of its most unkind cruelties, and as an intrepid explorer of some of its inner mysteries, alone and with her animal companions, a menagerie of familiars, the jungle friends spilling from tumbling foliage and the long depth of her dreamscapes.

Dolores Chiappone, Tied to the Bed (1932), oil on canvas, 30 x 24”, 2023

Childhood Abuse

Her father was from a family of Sicilian barbers and he longed to be a made man of the mafiosi clans migrating into roaring New York in the 1920s. In an interview I recorded with her two months before her death June 19, 2025, Chiappone recalled a nightmarish childhood of abuse and neglect – her drunken father, violent and terrifying, often threatening her. She explained, “…he would attack me, and kick me, and punch me, and he beat me with the razor strap…” She remembered him playing the part of a gangster and deliberately intimidating friends she had invited to dinner. If her father wreaked reckless beatings on her body, her mother’s disdain seared suffering into her mind. “My name in Spanish is, well, the name is Maria de Dolores, which is Mary of Agony, pain. My mother called me Dolores Marie, so she put the pain in front.” Dolores had no memory of either of her parents ever picking her up to hold her close, and her first recollection of being told she was loved came from her first husband, who became violent the day after he married her.

The childhood abuse contrasted sharply with her family home, which her father constructed on the lot next-door to his brother’s Rochester dwelling. Establishing a pattern, Chiappone described a fairy-tale setting, saying, “…my father built this little house that looked like a story-book house, it was a tiny house, for us, in the lot next door. It was so cute. He loved to build things and it was just like, a kind of a Victorian doll house…” The contrast between the magical appearance of physical reality and the darkness and suffering she experienced within her family life was a pattern repeated in her paintings. Approaching the end of her life, she was keenly aware of this opposition. She said her life was “…so full of little miracles I have to believe in magic, because it’s just been one tragedy and one miracle after the other, both… that duality again, both sides.”

Dolores Chiappone, The Mirage, 2025, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches

In 1942, when Chiappone was eleven years old, her family travelled from New York to Montebello, California, riding elegantly across the country in a long-hooded and ornamented 1936 Packard Eight with a covered spare on the side of the graceful, flared fenders covering the spoked wheels, bought from the proceeds of the doll house. She remembered the journey as an enchanted experience, saying, “It was so wonderful. The first plants I saw in the desert – I didn’t believe they were real. I had to get out and touch them, and the palm trees and the lemon trees, and I was just enchanted. They looked like Hollywood sets, you know, the desert did to me.”

Meeting Oscar Janiger

She bore two sons, but after seven years of marriage, the abuse she suffered drove her to hopelessness. Her husband had been seeing a U.C. Irvine psychiatrist named Oscar Janiger for his hypochondria, so after her second son was born, despairing Chiappone went to visit Dr. Janiger, too. He listened but offered no solution, so Chiappone made an appalling decision, “I had two choices, I could either commit suicide or go mad, so I decided, not being suicidal, that I would go mad, so I deliberately one day sat in a chair, folded my arms in my lap, and I left my mind.”

Dolores Chiappone, Untitled, oil on canvas, 40 x 30”, 1959

Now catatonic, Chiappone was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Janiger met with her husband and father, who were ashamed and angry. When Janiger came to see her afterward his mood was so intense it shook her from her deep withdrawal from the world. She recalled what he said,

He just spoke to me as though I were there. He spoke to me with great force, and he apologized to me. He said, “I’m so sorry,” and it caught my attention. “I had no idea what you were dealing with. There’s nothing wrong with you, Dolores,” he said, “you must get away from these people. Run!” …And so I was released from the hospital, and basically that’s what I did. I took my children, I had two babies, I had two small children, and I went to Mexico.

Magic Realism in Mexico

Submerged in the magic and mysteries of insanity, Chiappone was quickly immersed in the spirit and spell of the country, living a life of constant contrasts balanced between beauty and brutal violence, paralleling the surreal lives of Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Frida Kahlo, all of them women wanderers in Mexico, madness, and modernity. Reeling after her release from the hospital and the revelation of Janiger’s perspective, she found refuge in a cheap apartment in Mazatlán, raised high upon stilts with doors opening into empty space, sharing it with big black scuttling scorpions, and a smaller white species so venomous that victims die within minutes. The landlord shrugged and told her not to be afraid, “Only the good die young,” he said, “so you should survive just fine.”

Mazatlán was already the Sinaloan drug-dealing capital of Mexico, governed by lawless violence. Warned that unchaperoned young women were considered prey, she opened her apartment to people with criminal intentions. Once, a dubious group of four men arrived offering food and marijuana, Chiappone asked them to take her for a flight in their Piper Cub plane to see dolphins, whales, and leaping manta rays she often witnessed from the shore. She left her sons with two of the strangers and ascended above the coast. She asked if they could land on the beach, and the pilot, eager to please his passenger, put the plane down – but the sand was scattered with the dens of large land crabs and the Cub was caught by the uneven surface, flipping as it landed. Banged and battered, but otherwise uninjured, the three clambered onto the beach, watching as the waves swept away the wrecked plane. The castaways spent a sleepless night on the beach hopelessly building walls of driftwood to fend off thousands of crabs that saw them as food.

Dolores Chiappone, Fractilian Fairy, oil on canvas, 40 x 30", 1990

Truth Serum

Chiappone’s escape into the theatrical magic and madness of Mexico was short-lived, because her husband soon travelled to Mazatlán, and took away the children. Wretched and alone she returned to Los Angeles, to Janiger, the only man who had ever helped her. He injected her with sodium pentothal, an anesthetic used in psychiatric therapy with hypnosis as an effective method for helping patients relax and talk about their trauma, and by military interrogators as “truth serum.” Janiger recorded two sessions of his interviews with her as she drifted in the barbiturate haze, which Chiappone regarded as a therapeutic milestone, providing revelations that changed her forever. She realized she had not been living her own life, and singularly wanted to be a painter. Janiger put her into his experimental program for artists and writers exploring the effects of hallucinogens on creative people, and one day he dripped a few drops of Sandoz LSD into a glass of sparkling soda and handed it to her. Chiappone drank and was reborn.

Janiger felt a personal responsibility for Chiappone, who he had failed when she was under his care, and she became a member of a small community of a dozen patients exploring psychedelics. Transformed, she began painting as her vocation. She donned Beat black like her bohemian friends. In the early 1980s she painted an iconic self-portrait in fiery reds recalling by the experiences she had with Janiger. She recalled, “when I was doing LSD that whole group that I was with called me the magic bitch. So that’s what that is. That’s ‘The Magic Bitch.’”

Dolores Chiappone, The Magic Bitch, c. oil on canvas, 40 x 30”, 1985, Photo by Jesse Groves

In 1960, Chiappone decided to return to Mexico, beginning an itinerant life of moving back and forth across the border, spending six months there, then six months in the US, working illegally on her tourist visa and building a business for herself in furniture-making and decoration, painting, constantly dodging deportation. Her son David vividly remembered her visiting him and his brother in 1970, when he was twelve years old. As she emerged from the car in his grandparents’ driveway, dark, thin, and fashionably dressed in early seventies chic, she bore two canvases – her detailed The Tunnel, and Party in the Wall. David recalled,

When she was at a crossroads or if there was some conflict, she would use a painting almost as a talisman, she would write on the back of the painting what she wanted to happen, and often it happened the way she wanted. Her dream life was very sharp focused, unlike most people. She used her dreams in a similar way, or interpreted her dreams, but she described her dreams not as some outside element speaking to her through her dreams, but her speaking to herself, like her true self, your dreams are really a reflection of you, not telling the future…

Chiappone’s paintings were a palace of memories, knitting her present to her unkind past. They were her spells, binding her to her future.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS

, oil on canvas, 30 x 24”, 2023.Jpeg)