Raising Rossetti’s Ghosts

The Pre-Raphaelite artist turned grief into beauty, haunted by the ghost of Elizabeth Siddal

Michael Pearce / ���ϲ�����

28 Oct, 2025

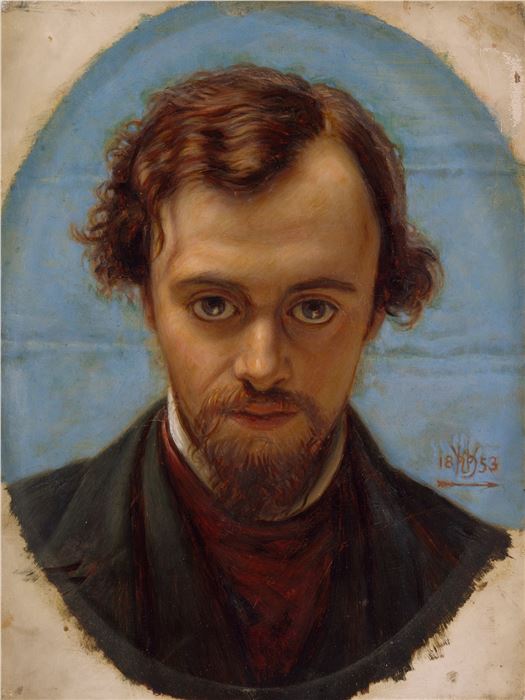

The walls of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s parlor were filled with mirrors of all sizes; the dining room decorated with black lacquered panels of Mandarin birds, animals, flowers, and fruit delicately worked in gold; cobalt tiles from the Netherlands; and portraits of Rossetti’s mother and sister. He was an enthusiastic collector of old oak furniture, Chinese blue and white vases, Persian tiles, and bric-a-brac he bought at auctions. As a liminal highlight of this cabinet of curiosities, a collection of his own paintings were mementos of living and dead women, hung together as a gathered assembly of his “stunners”. Two years after his death in 1882, his sister Christina published a poem she had written in 1856 casting an un-named artist almost as a vampire consuming his model, portraying her as a beautiful ideal, not as she really was, but as she lived in the artist’s imagination. She was clearly writing about her melancholy brother, imagining him as an aesthetic mourner preying on the beauty and memory of his dead wife.

William Holman Hunt, Portrait of Dante Gabriel Rossetti at 22 years of Age, 1853, Oil on panel 30.2cm x 22.9cm

In the Art-Room

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

Rossetti lived a revenant’s life on the threshold of the underworld. Jeanette Marshall kept a diary which spoke of the weight and impact of his wife Elizabeth Siddal’s opiated demise. As the daughter of Rossetti’s doctor, John Marshall, she was privy to some dark secrets. She claimed Siddal’s death was a suicide, but went further, asserting her spirit had returned from the dark grave to haunt her errant husband. Of Rossetti, Marshall wrote, “No doubt he had a wretched life since his wife’s death from poison she took herself! They had only been married 2 years, & she found herself superseded, & took laudanum. No doubt his grief was remorse, & for 2 years he saw her ghost every night! Serve him right too!” This gossipy account may be the fancy of a credulous girl, but Rossetti’s brother William reported that in November 1870 one of Rossetti’s servants, a sensible young woman, saw the specter of a woman haunting the top of the stairs of Rossetti’s Tudor House in Cheyne Walk. According to William, his brother Gabriel never saw a ghost, but he had become accustomed to the presence of Siddal’s shade in the house, conjured by other means.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Jane Morris (The Blue Silk Dress), 1868, Oil on canvas, 39.9" x 35.5"

After Siddal died, he secreted a long tress of her shining sienna hair in a drawer, revealing the treasure to Hall Caine decades after her death. Now, transmitted by Fanny Cornforth acting as medium in many séances, her ghost became his regular visitor. William Bell Scott told Alice Boyd, “…he really quite believes now in the communications of spirits. It seems Gabriel’s wife is constantly appearing (that is, rapping out things) at the séances at Cheyne walk! William affirms that the things so communicated are such as only she could know. No reasoning, seems to have the least effect with these absurd people.” At one of the séances the ghost of Siddall told the assembly she was always present at Cheyne Walk. Rossetti longed for her, casting his lost Lizzie as an absent but obsessive figure in his melancholy poem The House of Life: Without Her, writing,

What of her glass without her? The blank gray

There where the pool is blind of the moon’s face.

Her dress without her? The tossed empty space

Of cloud-rack whence the moon has passed away.

Her paths without her? Day’s appointed sway

Usurped by desolate night. Her pillowed place

Without her? Tears, ah me! For love’s good grace,

And cold forgetfulness of night or day.

What of the heart without her? Nay, poor heart,

Of thee what word remains ere speech be still?

A wayfarer by barren ways and chill,

Steep ways and weary, without her thou art,

Where the long cloud, the long wood’s counterpart,

Sheds doubled darkness up the labouring hill.

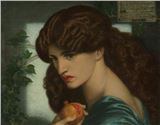

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, 1871–1872, Oil on canvas, 34 7/16" × 27 1/4"

A year after her death, and surrounded by spiritualist friends, and animals, and ghosts in his new riverside home, Rossetti painted Siddal wrapped in a mane of her rich red hair cast as Beata Beatrix with her eyes closed and face enraptured in a state of drugged ecstasy while a red bird fetched a white opium poppy to her. Sometimes, this bright and vermilion bird is strangely described as a dove of peace, but of course it is a phoenix, symbol of rebirth and regeneration, suggesting Siddal’s afterlife as a posthumous muse cast in the increasingly feverish and addicted theater of Rossetti’s sedated imagination – a Eurydice to his role as mourning Orpheus. His brother William said the painting was a portrait of “Beatrice in a Death-trance." The painting was reserved for the collection of William and Georgina Cowper-Temple, spiritualist friends of Mary Howitt, but while Rossetti worked on it, it hung unfinished for two years, iconic as an image of Lizzie’s long liminality, in the same room where séances were held in Tudor House to summon her spirit back to her beloved, led by Rossetti’s mistress Fanny Cornforth as medium.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Orpheus and Eurydice, 1875, Graphite on paper, 23.8" x 20.1"

Rossetti literally followed his beloved into the underworld like Orpheus longing for his Euridice, but the terrible goal of his real journey into Hades was an attempt to retrieve lost poetry, not his lost wife. After Siddal died, tragic Rossetti had tucked a notebook of his poems between her cheek and her glowing red hair as she lay in her coffin, and whispered to her silenced ears, “…the words it contained were written to her and for her, and she must take them with her for they could not remain when she had gone.” It was a romantic gesture of his grief, but a few years later he regretted it, for by then his papers were in disarray, and Siddal’s book contained the only copies of his verses. His opportunistic friend Charles Howell realized there was money in the collection and persuaded Rossetti to have her secretly exhumed so he could retrieve it for publication. Hall Caine remembered "…one night, seven and a half years after the burial, a fire was built by the side of the grave, and then the coffin was raised and opened. The body is described as perfect upon coming to light.” Like an incorruptible medieval saint destined to be venerated, or the revenants of the vampire craze, Siddal was reassuringly reported to be more beautiful than ever. The poetry was returned from darkness to light, brought loose from the grip of the grave with a strand of Siddal’s hair, said to have continued growing in her coffin. But these reassuring accounts of post-mortem perfection were benevolent exaggerations destined to become part of the fantastic mythology of the Pre-Raphaelites. Afterwards, repeating kind reports of his dead wife’s undecayed loveliness, Rossetti wrote to his brother William, describing the revolting condition of the book. “All in the coffin was found quite perfect,” he said,

but the book, though not in any way destroyed, is soaked through and through and had to be still further saturated with disinfectants. It is now in the hands of the medical man who was associated with Howell in the disinterment, and who is carefully drying it leaf by leaf. There seems reason to fear that some minor portion is obliterated, but I must hope this may not prove to be the most important part. I shall not I believe be able to see it for at least a week yet.

When he did receive the disinfected book, he found some sections destroyed entirely, and a great rotten hole penetrating all the leaves of his poem Jenny, but undeterred, he soon published a reconstructed and re-written version which was marketed with a nimbus of rumor about the exhumation generating enough morbid notoriety to satisfy the dark hunger for sensation enjoyed by his readers.

Rossetti’s growing interest in the dead worried his friends. The sculptor Thomas Woolner – who was one of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, observed it with incredulity and concern, complaining to Pauline Trevelyan of the gloomy gatherings at Cheyne Walk in a letter of March 1858, and repeating his fears almost verbatim a week and a half later to William Bell Scott, writing,

You will be sorry to hear that Gabriel Rossetti has taken up with that foolish, but growing abomination, spiritual rapping, and declares he can make ghosts and spirits talk to him, and do all he pleases. William told me, but I felt so filled with displeasure that I made no inquiries as to particulars. It is really saddening to know how this idiotic horror is spreading in England and America…

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine, 1874, Oil on canvas, 49.3" × 24"

Sometimes Rossetti’s ghosts were explained by other phenomena. Among the menagerie of pets kept at Tudor House there was a raccoon which made its winter bed in the drawer of a bureau in the hallway. Someone had shut the hibernating creature in, and Rossetti complained of mysterious noises, scrapings, and whimpers until the raccoon was discovered, much thinner, after its winter sleep, hungry, and sniffing for food.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS

, Oil on canvas.Jpeg)