The Art of Propaganda: Revolution, Napoleon, Colossus

European artists transformed revolution and political power into mythic images of divinity and fear

Michael Pearce / 黑料不打烊

27 Oct, 2025

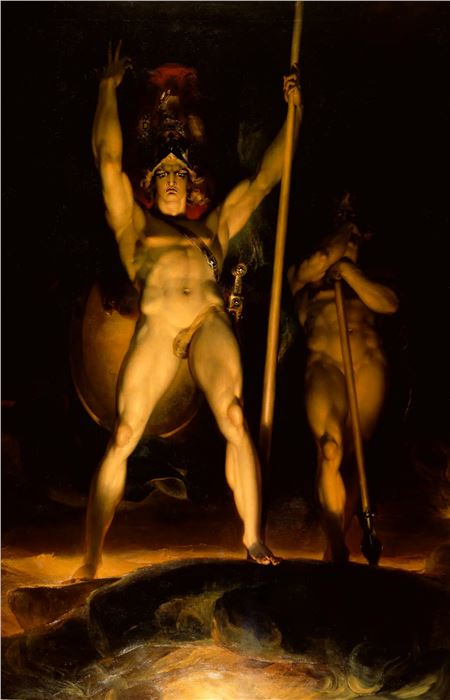

As a scandalous image of shameless masculine power and sensual strength, Thomas Lawrence’s spectacular painting Satan Summoning his Legions seemed to be a subversive advertisement for the libertine flowers that had become the harvest of the Enlightenment, showing the fallen angel in a pose of pride, concealed beneath modest chiffon. But Satan’s features were clearly those of a Gallic man, with the long nose and sensual mouth of a Southern European, not the earthy physiognomy of a plain-faced Anglo-Saxon. To class-obsessed British traditionalists at the turn of 1800, the painting was a spectacular metaphor for the shining evil of the dark lord of the revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte, who was the enemy of God.

Thomas Lawrence, Satan summoning his Legions, Oil on canvas, 4318 mm x 2743 mm, 1796-1797

Revolutionary Propaganda

Casting revolution as the righteous victory of citizens over tyranny, Jacques-Louis David had recommended using heroic Hercules as a symbol of republican France, and his powerful figure had quickly become accepted across Europe as an emblem of the king-slaying people. David founded his proposal on the revolutionary and poetic imagery of Erasmus Darwin, who wrote this invocation of the giant in his The Botanic Garden of 1791:

Long had the Giant-form on GALLIA’S plains

Inglorious slept, unconscious of his chains;

Round his large limbs were wound a thousand strings

By the weak hands of Confessors and Kings;

O’er his closed eyes a triple veil was bound,

And steely rivets lock’d him to the ground;

While stern Bastile with iron cage inthralls

His folded limbs, and hems in marble walls.

Touch’d by the patriot-flame, he rent amazed

The flimsy bonds, and round and round him gazed;

Starts up from earth, above the admiring throng

Lifts his Colossal form, and towers along;

High o’er his foes his hundred arms He rears,

Plowshares his swords, and pruning hooks his spears;

Calls to the Good and Brave with voice, that rolls

Like Heaven’s own thunder round the echoing poles;

Gives to the winds his banner broad unfurl’d,

And gathers in its shade the living world!

The colossus was representative of the collective power of the people. Artists took David’s recommendation to heart. The anonymous creator of Le Peuple Mangeur de Rois, (The King-Eating People) in the Revue de Paris in 1793, shows the colossal Hercules with club in hand dangling a king over the consuming fire that would annihilate the monarchy and aristocracy. The bearded giant wears a Phrygian liberty cap and stands before three tricolor banners.

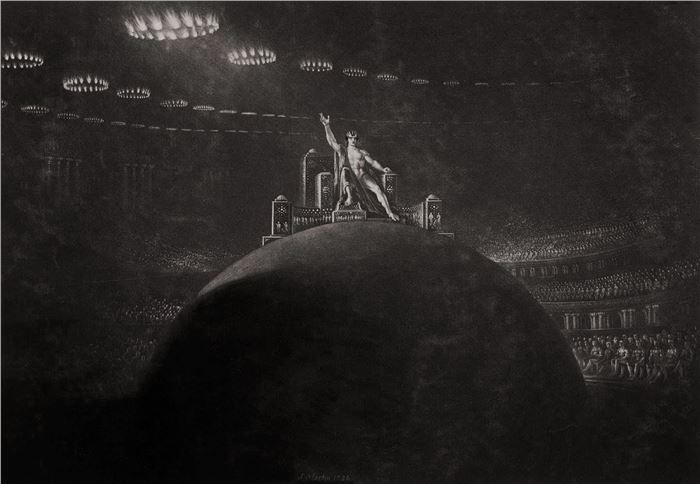

The Cult of the Supreme Being

At David’s direction, Hercules played a central role in Robespierre’s celebration of The Cult of the Supreme Being on June 8, 1794 as the official religion of the revolution in a great festival on the Champ de Mars, and throughout France. The spectacle was especially lavish in Paris, where David was put in charge of mounting an event worthy of the capital. After the script was written, his first focus was on creating an appropriate setting, and he designed and built an artificial mountain, creating the fantastic landscape of utopia in the Champs-Élysées, and arranging for performances and music to be staged upon it and around it on platforms decorated with plants, flowers, and burning braziers. Mirrors reflected light upon the performers. The symbolism was ancient. The sacred mountain was the holy place, where Moses was given the stone-cut letters of the law by God. The mountain was the divine symbol of the heavenly city. The mountain was where Christ ascended to heaven to sit at the right hand. It symbolized the primordial paradise of religious icons, once represented by Jesus and Mary, who were now replaced by Robespierre and his Jacobin Montagnard party as providers of access to utopia. Now David capped the mountain with Hercules, the colossus of the people.

, Muse虂e Carnavalet.Jpeg)

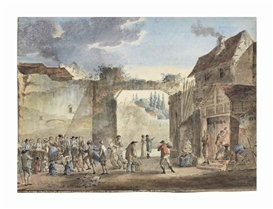

We know what David’s mis-en-scène looked like because many artists drew and painted the spectacle. Thomas Naudet painted the Parisian event in watercolor, and Pierre-Antoine Demachy in oils, and in the capital and across France, dozens of artists created line drawings of local performances, which were promptly printed and sold as souvenirs. The ceremonies began with fire consuming a statue representing atheism. A cart bore the allegorical figure of Summer as a monumental sculpture seated among sheaves of wheat, a cornucopia of produce, and the tools of the farm. She was sheltered by the gentle shade of a garlanded acacia, the immortal tree of the freemasons, and held aloft a liberty cap and a French national flag.

A crowd of thousands gathered to watch the processions and performances, under the flapping striped banners and tricolor flags of the revolution. A spearman wearing the long trousers of the sans-culottes and a Phrygian liberty cap led six draped oxen to the mountain dragging a triumphal carriage bearing the sculpture of the harvest goddess. All this was watched over by a sculpture of colossal Hercules at the mountain’s peak raised upon a triumphal column, his club at his side, and holding a sculpture of a winged woman balanced upon a ball – she was Fortune, who had favored the sans-culottes. A band played to celebrate the heroic figure. The crest of the sacred mountain was capped by another garlanded tree, with a pole raising a third liberty cap into the heavens above the spectacle. A repeated symbol, the liberty cap was a tall hat with the peak bent forward, known as the symbol of liberty, and an essential part of the uniform of the Paris proletariat of the “little men” who gave Robespierre’s party its power. Demachy’s painting shows the triumphant Hercules on his column towering over the huge crowd witnessing the display.

Lawrence’s Satan was a parody of David’s promotion of Hercules as colossus of the people. Lawrence showed the huge painting in May 1797 at the Royal Academy Annual Exhibition in London as Napoleon wrought devastating victories over Austria and Venice, and his soldiers landed briefly on the shores of Wales in a failed but terrifying attempt at an invasion of Britain in support of an unsuccessful Irish republican uprising against British rule. Swathed in fear, Satan was huge, towering over the other paintings of the show. A reviewer for the Times said it made “…the surrounding portraits look like the resemblance of so many Lilliputians." The gigantic evil of Napoleon’s paradoxical revolutionary imperialism was explicit.

The allegory of Lawrence’s painting caught the monstrous spirit of the unstable age of insurrection, as the demonic forces of the French military threatened the fragile ethical and social order of the new republic, bought by so much blood – but the shocking picture also reflected the occult and Gothic mood for evil, and the black magic that could summon demons. The French revolution had also been an insurgency against the entrenched power of the church, birthing secret fraternities and the roots of theosophy, currents first manifested in blooded Robespierre’s Cult of the Supreme Being.

Against this frenetic background of occultism, regicide, deicide, war, and the guillotine, Lawrence’s French Satan caused a gossipy sensation and inspired anger, even among the ignorant. Having no wit to help him, the critic Anthony Pasquin missed the demonic propaganda message, but enjoyed hating the picture anyway, telling off “callow” Lawrence with harsh enthusiasm for daring to create a history painting while lacking the anatomical training to pull off such a feat, and writing with a porridge of metaphor more ludicrous than the extravagance of the picture itself. “This picture is a melange,” he said,

made up of the worst parts of the divine Bonarotti, and the extravagant Goltzius: the figure of Satan is colossal and very ill drawn; the body is so disproportioned to the extremities, that it appears all legs and arms, and might, at a distance, be mistaken for a sign of the spread eagle. The colouring has as little analogy to truth as the contour, for it is so ordered that it conveys an idea of a mad German sugar baker, dancing naked in a conflagration of his own treacle! But the liberties taken with his Infernal Majesty, are so numerous, so various, and so insulting, that we are amazed the ecclesiastic orders do not interfere in the behalf of an old friend.

Perhaps Pasquin’s ignorance of the parody was enough to persuade Laurence to turn to making paintings of pretty aristocrats and abandoning his ambitions to become an allegorical wit.

Napoleon as Satanic Majesty

James Gillray, Destruction of the French Collossus, 1798

The satirist James Gillray understood Lawrence’s allegory better than Pasquin and went even further in his imaginative imagery. A year after Lawrence’s painting made its dramatic debut, he created his etching Destruction of the French Colossus, a fiery spectacle of resistance to the threat of Napoleon’s revolutionary tyranny. In it, the lightning bolts flashing from the wrath of God (who was protected by the shield of mighty Britannia) dismembered the hollow body of the cadaverous revolutionary colossus as it strode across the Mediterranean from France to Egypt, which Napoleon had invaded in May 1798, one foot trampling the Bible, the crucifix, and the scales of justice on the French coast, while the other was pierced by the pyramids on the Egyptian shore where Horatio Nelson obliterated the French fleet in August. A gorgon-headed mask fell from its empty neck, losing its liberty cap as it tumbled. Its shattered arms lost their grip upon the bloody guillotine ominously labelled “Fraternité,” and a text titled “Religion de la Nature,” promoting “Injustice, Oppression, Murder, Destruction” dropped earthward, likely a reference to William Wollaston’s enlightenment classic about an ethical system independent of religion.

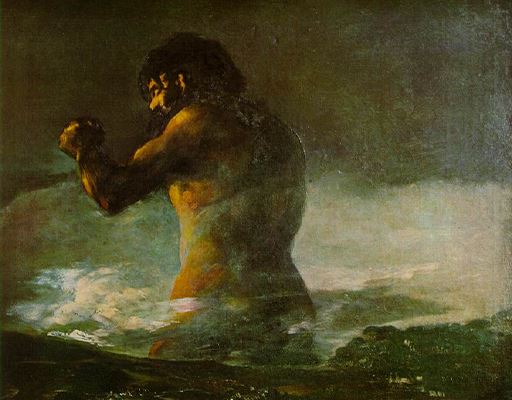

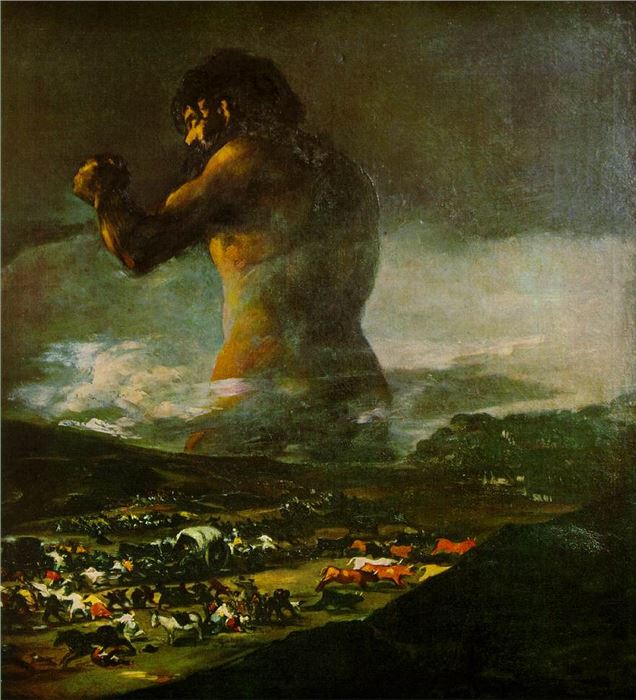

Goya’s Colossus

But the image endured. Like Lawrence, Francisco Goya painted the grotesquely muscular form of his Colossus of 1808 as a parody of Napoleon, both fearing and loathing the power of his military and ideological grip upon Europe. In 1807, French forces seized Portugal, and soon turned on their nominal Spanish allies. The colossus was turning toward a new enemy. The dark lord was coming to Madrid. By 1821, Napoleon was dead, but in 1824, apocalyptic John Martin painted Lawrence’s Satan in oratorical flow, presiding over the infernal council of hell. Now, his satanic majesty ruled the underworld, and the whispered spirit of revolution lived among the people.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS