Vernacular Photography: The Art of the Found

The line between amateur photography and vernacular photography is often a blurred one, and sometimes only defined by the discernible eye of a self appointed curator. The art of the found image is celebrated this month at two galleries on either coast, both New York’s ZieherSmith and Cohen Gallery in Los Angeles. Two private collections of photographs, one owned by vernacular curator David Winter and the other by gallery owner Stephen Cohen, are displayed respectively, and not only turn an eye onto vernacular photography as a genre of fine art, but also with the art of juxtaposition and the intention of curating as an art form.

Lori Zimmer / ���ϲ�����

31 Jul, 2013

The line between amateur photography and vernacular photography is often a blurred one, and sometimes only defined by the discernible eye of a self appointed curator. The art of the found image is celebrated this month at two galleries on either coast, both New York’s ZieherSmith and Cohen Gallery in Los Angeles. Two private collections of photographs, one owned by vernacular curator David Winter and the other by gallery owner Stephen Cohen, are displayed respectively, and not only turn an eye onto vernacular photography as a genre of fine art, but also with the art of juxtaposition and the intention of curating as an art form. Through the intentional groupings of these photographs, a creative dialogue is constructed, with Winter and Cohen finding art in the everyday snapshot, and assigning meaning through the relationship of one photograph to those that surround it.

Vernacular photography has its roots in the colloquial. With the rise of photography and the wide-spread availability of cameras, a generation of amateur photographers was born. These hobbyists used their instruments not to create allegorical or surrealistic photographs, but instead to document the day-to-day of domestic life, which in turn has enticed a cast of modern day collectors who have found beauty in these candid photos of the past. The irony of the journey is that these vacation photos, military and school portraits, photo booth images and family photos have traveled the same path that photography as a genre did; starting in the technical/documentary realm and then recontextualized into a fine art setting.

Vernacular photography has roots in art history whether it is intentional or not, and perhaps collectors like Winter and Cohen are attracted to the genre because of these loose associations. Like art brut or outsider art, the photographs can have a certain refreshing feeling that comes from the innocence of being captured by untrained photographers, who look at the world without being tainted by the lessons of photography school. Then there is the correlation with certain Dadaist exercises in making art, by finding beauty in the accidental, relying on chance (here the amateur’s decisive moment) to create true art.

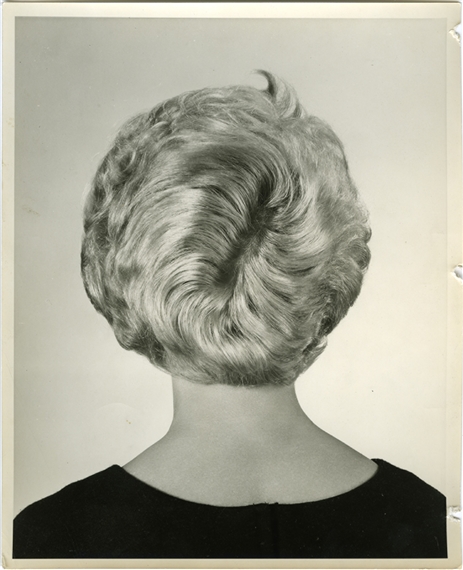

David Winter’s collection at ZieherSmith reaches beyond the usual inclusion of snapshots, postcards and mug shots and pushes into the oddly commercial, including photographs of hair salon examples which show portraits of the backs of women’s heads, photographs of candy for retro candy salesmen, and imagery intended for catalogs of furniture and machinery. His collection also delves into the slightly gruesome, with a series of medical specimens, interspersed with Polaroids of television actresses. Hung in grids, the collection reads as a series of well organized collages, with each snapshot interrelating to the next by sheer and intentional proximity.

David Winter’s collection at ZieherSmith reaches beyond the usual inclusion of snapshots, postcards and mug shots and pushes into the oddly commercial, including photographs of hair salon examples which show portraits of the backs of women’s heads, photographs of candy for retro candy salesmen, and imagery intended for catalogs of furniture and machinery. His collection also delves into the slightly gruesome, with a series of medical specimens, interspersed with Polaroids of television actresses. Hung in grids, the collection reads as a series of well organized collages, with each snapshot interrelating to the next by sheer and intentional proximity.Cohen’s collection also coincidentally includes the same hair salon imagery that Winter’s does, which illustrates the two curators’ similar allure to vernacular photography as a genre, collection and obsession. Cohen’s collection compares vintage amateur porn to Muybridge-like nudes, advertising to portrait candids, and a slew of simply odd photographs with no context – two masked men sitting in a living room, a woman pouring milk in bed, and a photograph of a chic 1920s style woman talking to a man dressed in tribal wear, many with captions written in ink on the photograph’s surface by an unknown author. It is these “odd” photographs that constitute vernacular photography at its best, the original context long forgotten, leaving an image rife with curiosity and enhanced with the kitschiness of fashion styles of days gone by.

Although sometimes derived from the untrained photographer, vernacular photography held influence on celebrated photographers beginning with Walker Evans, and continuing with iconic photographers like Nan Goldin, Sally Mann, Robert Frank and William Eggleston. This influence raises the question of whether a trained or known photographer can create vernacular photography, or if they are incapable simply from their ingrained knowledge of aperture settings and compositional design.

This is what perhaps draws collectors of vernacular photography to amass such collections. Aside from the thrill of the hunt of finding the odd photographic treasure in a thrift store or flea market, there is a feeling of absolute purity in the accidental. The collector can then become the artist and curator, using the photographs themselves as a medium. The collector/curator’s intention and creativity transform each photograph into an element of purpose, placing dialogue and cohesion on an otherwise box of odd photographs. David Winter and Stephen Cohen go beyond simply being collectors, instead flexing their own creative muscles by asking the viewer to look further into the element of day-to-day life by drawing relationships between the imagery that constitutes it.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS