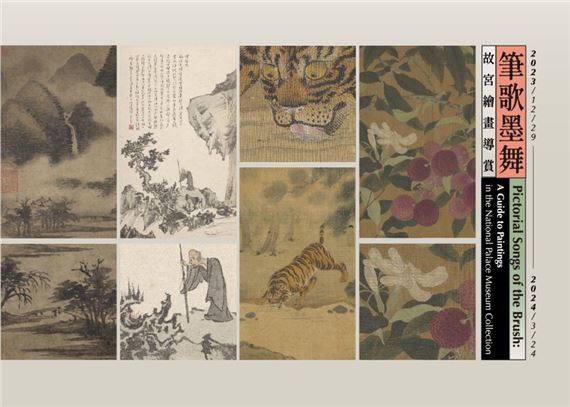

Pictorial Songs of the Brush: A Guide to Paintings in the National Palace Museum Collection (2024-I)

The history of Chinese painting can be compared to a symphony. The styles and traditions in figure, landscape, and bird-and-flower painting have formed themes that continue to blend to this day into a single piece of music. Painters through the ages have made up this "orchestra," composing and performing many movements and variations within this tradition.

It was from the Six Dynasties (220-589) to the Tang dynasty (618-907) that the foundations of figure painting were gradually established by such major artists as Gu Kaizhi and Wu Daozi. Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with variations based on geographic distinctions. For example, Jing Hao and Guan Tong depicted the drier and monumental peaks to the north while Dong Yuan and Juran represented the lush and rolling hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through Huang Quan's style, which contrasts with that of Xu Xi in the Jiangnan area.

In the Song dynasty (960-1279), landscape painters such as Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Tang created new manners based on previous traditions. The transition in compositional arrangement from grand mountains to intimate scenery also reflected in part the political, cultural, and economic shift to the south. Guided by the taste of the emperor, painters at the court academy focused on observing nature combined with "poetic sentiment" to reinforce the expression of both subject and artist. Painters were also inspired by things around them, leading even to the depiction of technical and architectural elements in the late eleventh century. The focus on poetic sentiment led to the combination of painting, poetry, and calligraphy (the "Three Perfections") in the same work (often as an album leaf or fan) by the Southern Song (1127-1279). Scholars earlier in the Northern Song (960-1126) thought that painting as an art had to go beyond just the "appearance of forms" in order to express the ideas and cultivation of the artist. This became the foundation of the movement known as literati (scholar) painting.

The goal of literati painters in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), including Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), was in part to revive the antiquity of the Tang and Northern Song as a starting point for personal expression. This variation on revivalism transformed these old "melodies" into new and personal tunes, some of which gradually developed into important traditions of their own in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As in poetry and calligraphy, the focus on personal cultivation became an integral part of expression in painting.

Recommended for you

The history of Chinese painting can be compared to a symphony. The styles and traditions in figure, landscape, and bird-and-flower painting have formed themes that continue to blend to this day into a single piece of music. Painters through the ages have made up this "orchestra," composing and performing many movements and variations within this tradition.

It was from the Six Dynasties (220-589) to the Tang dynasty (618-907) that the foundations of figure painting were gradually established by such major artists as Gu Kaizhi and Wu Daozi. Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with variations based on geographic distinctions. For example, Jing Hao and Guan Tong depicted the drier and monumental peaks to the north while Dong Yuan and Juran represented the lush and rolling hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through Huang Quan's style, which contrasts with that of Xu Xi in the Jiangnan area.

In the Song dynasty (960-1279), landscape painters such as Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Tang created new manners based on previous traditions. The transition in compositional arrangement from grand mountains to intimate scenery also reflected in part the political, cultural, and economic shift to the south. Guided by the taste of the emperor, painters at the court academy focused on observing nature combined with "poetic sentiment" to reinforce the expression of both subject and artist. Painters were also inspired by things around them, leading even to the depiction of technical and architectural elements in the late eleventh century. The focus on poetic sentiment led to the combination of painting, poetry, and calligraphy (the "Three Perfections") in the same work (often as an album leaf or fan) by the Southern Song (1127-1279). Scholars earlier in the Northern Song (960-1126) thought that painting as an art had to go beyond just the "appearance of forms" in order to express the ideas and cultivation of the artist. This became the foundation of the movement known as literati (scholar) painting.

The goal of literati painters in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), including Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), was in part to revive the antiquity of the Tang and Northern Song as a starting point for personal expression. This variation on revivalism transformed these old "melodies" into new and personal tunes, some of which gradually developed into important traditions of their own in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As in poetry and calligraphy, the focus on personal cultivation became an integral part of expression in painting.

Artists on show

Contact details

ARTISTS

ARTISTS