Robert Colescott

Blum & Poe is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Robert Colescott (b. 1925, Oakland, CA; d. 2009, Tucson, AZ). This exhibition represents the first significant overview of ColescottŌĆÖs work in Los Angeles, and the most comprehensive selection of paintings and drawings to be on view in California in over twenty years.

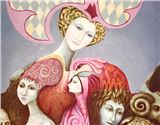

Over a nearly six-decade career, Robert Colescott established himself as a singular voice in American painting. With his distinctive style of figuration, Colescott laid bare issues of systemic racism and the omission of black subjects within the genre of history paintingŌĆöoffering up a disturbing yet poignant critique of male chauvinism, sexual misconduct, and interracial relationships. The exhibition at Blum & Poe is organized thematically, with individual galleries dedicated to many of these subjects that permeated ColescottŌĆÖs work for much of his life. A forthcoming catalogue with new scholarly essays will follow this exhibition.

Works on view foregrounding ColescottŌĆÖs interest in politics and current affairs include Kitchen Assassination (1971), a chaotic composition depicting the 1968 shooting of Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel, and its corresponding painting, Assassin Down (1968-69), illustrating the shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald. These works, along with more historical representations of war and strife, such as El Mahdi (1968-69) and Poncho Villa (1968-69), illustrate ColescottŌĆÖs attraction not only to his own American story, but also to the stories and histories of other cultures. Of particular note, El Mahdi was painted after ColescottŌĆÖs time as the first professor of painting at the American University in Cairo, Egypt in 1966-67. This experience proved to be formative for the artist, as he stated, ŌĆ£Egypt submerged me in my non-European identity.ŌĆØ This exposure to myriad cultures and art forms would later aid Colescott in forming his own uniquely ŌĆ£AmericanŌĆØ style of painting and storytelling. ColescottŌĆÖs aesthetic maintained elements of Pop art and formally conjured both the Chicago Imagists and the Bay Area Figurative painters (art historical movements which coincided with his own artistic maturation period). His work has defined itself largely through its bracingly satirical sensibility and biographical nature.

Beginning in the 1970s, while holding various teaching positions in the Bay Area and Pacific Northwest, Colescott focused his attention repeatedly on the subject of sexŌĆöspecifically interracial relations and the perceived power dynamic between men and women of that time. These issuesŌĆöwhich would hold a place of prominence in ColescottŌĆÖs work for decadesŌĆöviewed now forty years later, have proven to be tremendously topical and relevant in this moment of national reckoning. In ColescottŌĆÖs satirical fashion, paintings such as Fears: the Big Bad Wolf (1983) and Peeping Tom: He Was Drawn to the Lighted Window like a Moth to a Flame (1973), take a self-aware view of the male gaze and through parody address such dark stereotypes as the perceived danger of black men to white women, and sexual misconduct in the workplace.

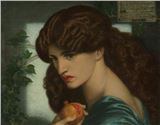

By fearlessly appropriating masterworks from art history and offering a revisionist narrative with black men and women in positions of prominence, Colescott subverted centuries of preconceived tradition in Western culture. On view are key works from ColescottŌĆÖs ŌĆ£BathersŌĆØ series (1984-85), which place black protagonists into the foreground of classical turn of the century paintings by Renoir and C├®zanne, immediately shifting oneŌĆÖs understanding of perceived beauty, power, and historical accuracy in the canon of Western painting. For much of the 1970s, ŌĆś80s and into the ŌĆś90s, Colescott would offer this reassessment of art history in such iconic works as George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975). Here, Colescott upends Emanuel LeutzeŌĆÖs famous 1851 portrait of George Washington, recasting the expedition with a black Carver at the helm of the boat in WashingtonŌĆÖs stead.

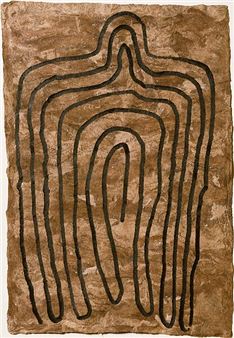

ColescottŌĆÖs late work, executed while living and teaching in Arizona, shows an artist still focused on depicting historical painting through his own lens, yet with a looser and more gestural compositional style. One work on view, W.M.D.: Remembering Sardanapalus (2004-06), is adapted from DelacroixŌĆÖs Death of Sardanapalus (1827). As the title would suggest, here Colescott is making a commentary on the invasion of Iraq during the Bush administration tenure, hence reminding his viewer as he has done so many times before, that history always finds a way of repeating itself. As observed by the curator Daniel Cornell, ŌĆ£In this late work, the delight of unrestrained laughter which has accompanied so much of the artistŌĆÖs best work, is buttressed by his refusal to allow subject matter to dictate the constraints of his painted surfaces.ŌĆØ

Recommended for you

Blum & Poe is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Robert Colescott (b. 1925, Oakland, CA; d. 2009, Tucson, AZ). This exhibition represents the first significant overview of ColescottŌĆÖs work in Los Angeles, and the most comprehensive selection of paintings and drawings to be on view in California in over twenty years.

Over a nearly six-decade career, Robert Colescott established himself as a singular voice in American painting. With his distinctive style of figuration, Colescott laid bare issues of systemic racism and the omission of black subjects within the genre of history paintingŌĆöoffering up a disturbing yet poignant critique of male chauvinism, sexual misconduct, and interracial relationships. The exhibition at Blum & Poe is organized thematically, with individual galleries dedicated to many of these subjects that permeated ColescottŌĆÖs work for much of his life. A forthcoming catalogue with new scholarly essays will follow this exhibition.

Works on view foregrounding ColescottŌĆÖs interest in politics and current affairs include Kitchen Assassination (1971), a chaotic composition depicting the 1968 shooting of Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel, and its corresponding painting, Assassin Down (1968-69), illustrating the shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald. These works, along with more historical representations of war and strife, such as El Mahdi (1968-69) and Poncho Villa (1968-69), illustrate ColescottŌĆÖs attraction not only to his own American story, but also to the stories and histories of other cultures. Of particular note, El Mahdi was painted after ColescottŌĆÖs time as the first professor of painting at the American University in Cairo, Egypt in 1966-67. This experience proved to be formative for the artist, as he stated, ŌĆ£Egypt submerged me in my non-European identity.ŌĆØ This exposure to myriad cultures and art forms would later aid Colescott in forming his own uniquely ŌĆ£AmericanŌĆØ style of painting and storytelling. ColescottŌĆÖs aesthetic maintained elements of Pop art and formally conjured both the Chicago Imagists and the Bay Area Figurative painters (art historical movements which coincided with his own artistic maturation period). His work has defined itself largely through its bracingly satirical sensibility and biographical nature.

Beginning in the 1970s, while holding various teaching positions in the Bay Area and Pacific Northwest, Colescott focused his attention repeatedly on the subject of sexŌĆöspecifically interracial relations and the perceived power dynamic between men and women of that time. These issuesŌĆöwhich would hold a place of prominence in ColescottŌĆÖs work for decadesŌĆöviewed now forty years later, have proven to be tremendously topical and relevant in this moment of national reckoning. In ColescottŌĆÖs satirical fashion, paintings such as Fears: the Big Bad Wolf (1983) and Peeping Tom: He Was Drawn to the Lighted Window like a Moth to a Flame (1973), take a self-aware view of the male gaze and through parody address such dark stereotypes as the perceived danger of black men to white women, and sexual misconduct in the workplace.

By fearlessly appropriating masterworks from art history and offering a revisionist narrative with black men and women in positions of prominence, Colescott subverted centuries of preconceived tradition in Western culture. On view are key works from ColescottŌĆÖs ŌĆ£BathersŌĆØ series (1984-85), which place black protagonists into the foreground of classical turn of the century paintings by Renoir and C├®zanne, immediately shifting oneŌĆÖs understanding of perceived beauty, power, and historical accuracy in the canon of Western painting. For much of the 1970s, ŌĆś80s and into the ŌĆś90s, Colescott would offer this reassessment of art history in such iconic works as George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975). Here, Colescott upends Emanuel LeutzeŌĆÖs famous 1851 portrait of George Washington, recasting the expedition with a black Carver at the helm of the boat in WashingtonŌĆÖs stead.

ColescottŌĆÖs late work, executed while living and teaching in Arizona, shows an artist still focused on depicting historical painting through his own lens, yet with a looser and more gestural compositional style. One work on view, W.M.D.: Remembering Sardanapalus (2004-06), is adapted from DelacroixŌĆÖs Death of Sardanapalus (1827). As the title would suggest, here Colescott is making a commentary on the invasion of Iraq during the Bush administration tenure, hence reminding his viewer as he has done so many times before, that history always finds a way of repeating itself. As observed by the curator Daniel Cornell, ŌĆ£In this late work, the delight of unrestrained laughter which has accompanied so much of the artistŌĆÖs best work, is buttressed by his refusal to allow subject matter to dictate the constraints of his painted surfaces.ŌĆØ

Artists on show

Related articles

In a politically correct culture, itŌĆÖs liberating and unnerving to step into Robert ColescottŌĆÖs exhibition at Blum and Poe, where the late painter revels in representations of stereotypes.

In the late artistŌĆÖs paintings, on view at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, good is evil, right is wrong and no one is innocent

ARTISTS

ARTISTS