Book Review: Art, Magic, and the Surrealist Mind

André Breton's "Magic Art" explores the intersection of art and magic but lacks depth, meandering through surrealist ideas, esoterica, and historical references without clear philosophical insight

Michael Pearce / 黑料不打烊

26 Feb, 2025

Magic Art, by André Breton. Fulgar Press.

A foreword by Robert Shehu-Ansell explains Magic Art was first available in 1957, when it was printed as part of a subscription edition of a thematic series of five books summarizing art published by Le Club Français du Livre. It was a surprisingly bourgeois venue for the anarchist Breton, the dogmatic leader to an unruly and disobedient group of artists whose egalitarian sensibilities and psychological explorations squared poorly with the cautious preoccupations of conservative elements of the middle class, but by 1957, feisty Breton was already mellowing into a sexagenarian age immersed in the quieter preoccupations of poetry, publishing his hermetic meditations on Joan Miró’s Constellations, a series of gouache paintings considered his most important work. He had struggled to complete Magic Art on deadline, and hired Gérard Legrand to edit and write, based on his own notes and text – consequently the book reads as a meandering mash of Breton’s thoughts about art, anthropology, and ritual channeled through Legrand’s pen, paralleling the relationship of a medium to the spirits of another plane.

Breton’s preoccupation with the orphic arts dated to the Second Surrealist Manifesto of 1929, which demanded “the occultation of surrealism,” but the formulas of sorcery and spells were uncomfortable bedfellows with Freudian analysis and random juxtapositions of dreams. Perhaps inevitably, Magic Art could only be an interesting ramble through the anthropology of masks and ritual objects, with gnomic references to the ecliptic luminaries of ritual magic like Eliphas Levi and Aleistair Crowley, without providing particularly deep insight into either magic or surrealism. Nevertheless, the book formalized Breton’s fascination with esoterica – he was a lifelong collector of the ephemera of tribal religious practices and bought crude paintings by the Haitian vodou priest and untrained painter of Port-au-Prince, Hector Hyppolite, and his studio was filled with mysterious objects that sustained and reinforced his late orientalist preoccupations with primitivism.

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876, watercolor.

The thought of such egalitarian collectivists as the proto-communist Fourier, admired by Marx and Engels, and the vapid idealism of limo-liberal John Dewey infects the pages, which are loaded with his patronizing delusions about the superiority of the primitive mind, with his bourgeois fantasies of equity trumping quality and reducing all art to the lowest denominator, and with his preference for the aesthetics of supposedly arcadian tribesmen untainted by the sophistication of highly evolved (and obviously evil) capitalist art. Mixing this transatlantic potion of utopianism with the orderly and aristocratically hierarchal ideas of ritual magic seems a bizarre conception, but it is fitting for its time, for only in the strange melting pot of the Cold War West could such contradictions exist in confluence. It is entirely plausible that Le Club Français du Livre was funded by the CIA as part of their propaganda efforts to promulgate this soft left. Breton had rejected Stalin in 1939, as had American communists, and the post-war American government was keen to emphasize their support for a soft European left. During the war Breton had been rescued by Varian Fry’s clandestine Emergency Rescue Committee, assisted by the Museum of Modern Art’s Alfred Barr, and while in exile worked for a propaganda radio channel the Voice of America, and frequently would have crossed paths with Nelson Rockefeller, President Roosevelt’s right-hand-man, the eminence grise of the United States’ emerging cultural dominance in the West, and principal funder of MoMA, and enthusiastic collector of so-called primitive African, Oceanic, and Pre-Columbian art which he gathered together as the Museum of Primitive Art in 1957. Luxurious publications like the lavishly illustrated five volume set offered by Le Club Français du Livre were improbably fine in the context of impoverished post-war Europe, hinting at a budget padded by additional funding, perhaps distributed through transatlantic sources like Farfield, or some other international shell, notorious for financing subtle vehicles subverting the communist cause, and, a cynic might add, providing international publicity for Rockefeller’s new museum. Breton, as a notorious ex-communist apostate was an ideal to be upheld.

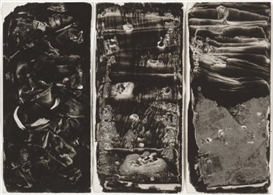

Breton founded Magic Art upon ideas originating from Novalis, the German romantic poet who coined the term “magical idealism” as a literary expression of the meeting of the imagination with nature – the arts breaking down the barriers between the formality of rational modern thought and enchanted nature. Religion offered conciliation and resignation with fate under the eye of an all-seeing God, while magic manifested will and agency under the discipline of ritual. Magic offered protest, command, and pride, while religion offered prayer and propitiation. Magic and science agreed that the universe operated on complex laws, but magicians accepted the law of correspondences dating from Pythagoras and Plato and believed they had influence over great things and events if they controlled their smaller analogues. With little commentary, a copious stream of black and white photographs of tribal masks, dolls, and sundry curiosities filled the margins of the book as Breton expanded on animism and explored the spiritual relationship between creativity and manifestation of will in ritual magic. It is a seductive book, offering an alternative to the dull conventions of bourgeois life.

Martin Schongauer, Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, c. 1470–75, engraving.

Plucked from the pages of renaissance emblem books and muddled with illustrations of demons and witches, a cryptic stream of occult and alchemical images, many apparently chosen more for their mystery and drama than for their emblematic significance, liberally illustrates the pages, too, and it is regrettable that Breton – who possessed so sharp a mind – did little to explain their meaning, although he surely knew of the quadriga. Their inclusion exploits the unfortunate and false reputation attached to emblems and alchemical symbolism as occult magical symbols. This is unfortunate, for alchemical images were often simply scientific allegories illustrating chemical experiments no more magical than mixtures of acid and alkaline and antimony, no more ritual than reactions in a retort, yet mysteries to ignorant minds who were prepared to burn alive the explorers who opened the universe to modern science, and the history of emblems is ethical and devout, neither dark, nor wicked, and although its imagery was often enigmatic, the quadriga was a delightful four-tiered system of revelatory interpretation that led through literal, allegorical, moral, and metaphysical exegesis.

Magic Art arrives under a dark and cryptic cover of gunmetal grey cloth embossed with broad black and gloss letters and the yellow emblem of an engraved hand clenched beneath a knuckled candle. Masks of paired eyes flap like moths magnetically drawn to the power of the flame, which is the icon of enlightenment. The mask is an emblem of mystery and hidden identity, so the interpreting iconographer must believe that the message of this enigmatic puzzle is that those who approach the light of God’s wisdom contained in this strange book do so under a cloak of self-concealment. Thus, using the wise interpretation offered by the quadriga, an image of a candle-bearing hand is first simply a mysterious symbol of a candle-bearing hand, but it is also necessarily a hand endowed with Christian enlightenment, and yes, perhaps it might be interpreted as magical power in certain circumstances when attached to certain stories, but more importantly it is an image of the agency of God, and it implied that we all dwell within the light of God’s revelation.

Breton attributed the source of art to magic – making a work of art was an art of belief, in faith in the uncreated thing, but his writing rambled through a survey of art history with unproductive digressions into Leonardo Da Vinci, mannerism, and wandered well into the woods of art history and used many words to say little. He returned to his subject with vague insights into Caspar David Friedrich’s injunction to “Close your physical eye, that you may first see your painting with the eye of the spirit. Then bring up into the day what you have seen in your night, so that its action may be exerted in return on other beings, from the outside in,” and claiming the magical throne for his surrealist friends, especially Guillaume Apollinaire, whose nominally magical painting The Rotting Enchanter, and writings The Moon King, and The Prague Stroller, as well as some of his poems which were explicitly about magical subjects, and Giorgio de Chirico, who flourished on the secret lives of things, and according to Breton, longed for an enchanted world experienced by initiates.

A central section of the book is laid out in grey pages as a tedious survey of the thoughts and responses to five questions Breton asked of the illuminati of French art of the mid-twentieth century about art and magic. The bulk of them can be quickly dismissed as insubstantial brushoffs, frankly, embarrassing to Breton’s stature if he imagined himself as an intellectual. It is possible that some unhappy encyclopedists with stained shirts and yellow teeth and bitten fingernails might be interested in the minutia of what Leonora Carrington, André Malraux, Georges Bataille, and a cadre of a hundred other mid-century Europeans had to say about what Monsieur J. -A. Rony’s thoughts on the end of magic might have been, but I suspect most of us will skip those pages.

In 1991, Gérard Legrand claimed the book represented, “…the free strolling of a great mind through a world familiar to him,” which was a euphemism for a book lacking philosophical clarity. Breton’s surrealist juxtapositions lacked scholarly insight either because of the rambling misfortunes of his age or his consistent failure to research adequately. Breton pointed out that there had been many books written about science and magic, but none about art and magic. Although he wanted to fill that gap, he lacked the wisdom to write it. Instead, he wrote a bad book about magic and a worse book about art.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS