Earth Day and Art: NatureвҖҷs Beauty and the Power of Environmental Art

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, art has become a tool to capture our planetвҖҷs beauty, and with an ever-growing ecological footprint has grown to be key in raising awareness of our demandsвҖҷ impact

Maya Garabedian / әЪБПІ»ҙтмИ

Apr 22, 2020

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, art has become a tool to capture our planet’s beauty, and with an ever-growing ecological footprint has grown to be key in raising awareness of our demands’ impact.

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982. Field planted in Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan. Courtesy of Agnes Denes, Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects NY, and Public Art Fund

Around the world, April 22 is recognized as Earth Day, a reminder of the importance of protecting our environment. This year marks 50 years of Earth Day’s official recognition, originally created in 1970 to raise awareness of global environmental issues, encourage activism, and bring people together through educational events and eco-friendly celebrations. The initial seeds of Earth Day, however, were planted in 1960, when river fires, oil spills, and information about the toxicity of pesticides drove scientists and environmentalists to demand political action. The state of Wisconsin led the way by organizing public teach-ins, rallying university students for picket sign protests, and inspiring people everywhere to find their voice. This eco-conscious self-expression established the Environmental Art movement we know today.

Philip James de Loutherbourg, Coalbrookdale by Night, 1801, oil painting on canvas. Courtesy of Art UK and the Science Museum, London

Even before the ‘60s and ‘70s, artists used their work as an outlet to emphasize connection with nature, express discontent with peoples’ mistreatment of the environment, and highlight the beauty of the natural world. As early as Romanticism (1780-1850), artists began celebrating the magnificence of nature and peoples’ connection to it and recognizing the ways the Industrial Revolution began to negatively affect the environment. The latter is depicted in Philip James de Loutherbourg’s Coalbrookedale by Night, where the skyline of an iron-making town is illuminated by a coal plant’s fiery smog. This concern with environmental degradation followed into Realism (1848-1900), as an unavoidable undertone in portrayals of daily life and common laborers in their true surroundings.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1906, oil painting on canvas. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

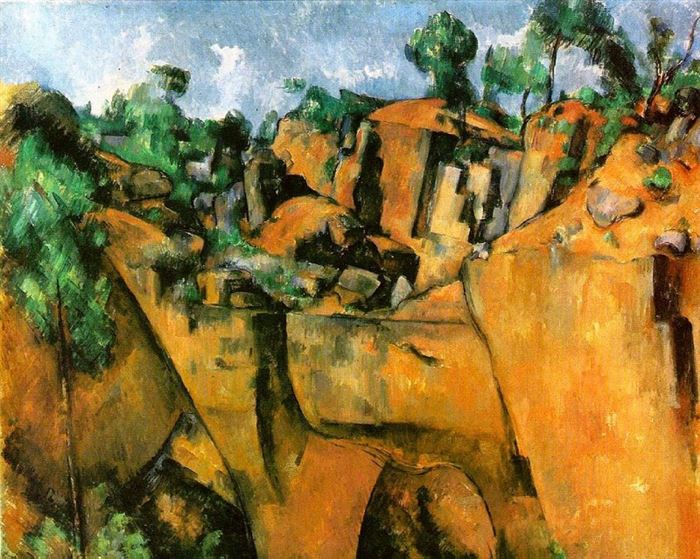

Positive depictions of the beauty of the natural world came with Impressionism (1865-1885) and continued into Post-Impressionism (1885-1910). Impressionist Claude Monet expressed perceptions of nature en plein air, straying from his predecessors’ traditional approaches to landscape paintings. His love for nature and his manipulation of light in scenery paintings shows a deeper, more emotional connection to his surroundings. In a similar style, Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne ignored the classical stylistic laws of nature painting: each aspect was now seen as an independent object within a space rather than parts of a scene. While Cézanne’s work lacked the intimacy, animation, and soothing color palette that defined Monet’s, he expressed his appreciation of nature through abstraction, flat brushstrokes, and dark lines. By reducing nature to its simplest form, shapes, his work is introspective and meditative, aiming to create “harmony parallel with nature,” emphasizing the role of a respectful observer.

Paul Cézanne, Bibemus Quarry, 1895, oil painting on canvas. Courtesy of Paul Cézanne

Art of the 20th century was highly experimental and evolutionary—the radical thinking of Realists like Gustave Courbet developed into avant-garde styles, Paul Cézanne’s flat brushwork influenced the aesthetics of Fauvism (1900-1935), and his rejection of art directly copying nature paved the way for Cubism (1907-1914). The 20th century had solidified the idea that art was a means of self-expression, a way for people to cope with the world around them, and a platform to make a statement about socio-political issues. Expressionism (1905-1920) and Surrealism (1916-1950), stemming from conflicted worldviews and discontent with political choices like World War I, furthered the idea of art as an extension of self. Amidst these larger movements, a lesser known, but equally powerful movement, Environmental Art, began taking shape.

The Environmental Art movement is broad, featuring a wide range of media, techniques, and practices, and is still in progress today. Some other movements it includes are Land Art, the process of incorporating art directly into a landscape, such as sculpting the earth itself and building structures out of natural materials, and Sustainable Art, work that reflects the four pillars of sustainability: ecology, social justice, non-violence, and grassroots democracy. Environmental Art began in the late 1960s with artists like Nils-Udo, Agnes Denes, and Robert Morris, who were interested in making work that explored the relationship between humans and nature, while also raising awareness of ecological problems and anthropogenic harm.

Nils-Udo, Waterhouse, 1982, installation of spruce trunks, birch branches, willow switches, and sod on Wadden Sea mudflats, Holland. Courtesy of L’Oeil de la Photographie

German artist Nils-Udo, one of the most prominent figures of Environmental Art, is known for taking a utopian approach to Land Art, where “every non-natural element is ruled out as impure.” Working directly in and with nature, using only materials found in each natural space, Nils-Udo has created beautiful site-specific art for the last 60 years. Robert Morris’ Environmental Art, on the other hand, was more of an aspect of his overall interdisciplinary practices. While it may seem paradoxical for a Minimalist to have such range, his work as a sculptor and performance artist led him to Process Art, or Anti-Form — the idea of embracing chance, temporality, and organic processes in art.

Robert Morris, Observatorium, 1977, two concentric earth walls, steel visors, stone wedges, and pathways forming an open polder landscape in Flevoland, Netherlands. Courtesy of Land Art Flevoland

Agnes Denes, a Hungarian-born conceptual artist who relocated to New York City, is often referred to as “the grandmother of Environmental Art”. Her interest in the human perception of nature, stewardship, and the connection between socio-political and ecological issues are very evident in her most famous piece, Wheatfield – A Confrontation. Denes, commissioned by the Public Art Fund, spent four months planting and maintaining a field of golden wheat on two acres of a rubble-strewn landfill in the middle of lower Manhattan, two blocks from Wall Street, facing the Statue of Liberty. Considering the land was worth $4.5 billion, Denes’s desire to have Wheatfield there was a symbol of food, waste, and world trade, stating that “it called attention to our misplaced priorities.” After harvesting over 1,000 pounds of healthy wheat in the summer of 1982, the grain traveled to 28 cities worldwide in “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger,” organized by the Minnesota Museum of Art.

John Sabraw, Chroma S4 Tribute, 2017, mixed media on aluminum composite panel. Courtesy of McCormick Gallery

Other artists, beyond the initial pioneers, that have contributed greatly to the movement include John Sabraw and Olafur Eliasson. Their art focuses on drawing attention to the current state of our environment. Sabraw takes toxic runoff from the Ohio River region and produces his own pigments using leftover oxidized sludge from coal mines. By using the water’s heavy metals rather than importing iron oxide to make his pigments, his work reminds viewers of our global pollution problem and suggests localized action. Similarly, Eliasson emphasizes the damaging effects humans have had on the environment. In his installation, Your waste of time, which has toured worldwide, chunks of ice that had broken off Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, were displayed in a refrigerated, solar-powered gallery space. As museumgoers made their way through the art, they were forced to confront the effects of anthropogenic global warming.

Olafur Eliasson, Your Waste of Time, 2006, ice in room with solar panels, photo by Jens Ziehe. Courtesy of Olafur Eliasson

Since the 1960s, with the inception of Earth Day and the formation of a solidified Environmental Art movement, the art world has developed from depictions of the natural world to using art as a call to action. This year’s Earth Day is especially poignant as a global pandemic has furthered our awareness of human-induced climate change. Looking at our planet through the lens of art provides a powerful method of understanding when it comes to the needs of our environment moving forward.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page