Handbags of the Apocalypse

Walk through the downtown of any major world city, and you’ll see the intersection of fashion and status carried on women’s shoulders or stacked like

Alexander Boldizar / C-Arts

America hasn’t known rationing since World War II, but Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue both recently restricted purchases of the popular Yves Saint Laurent Downtown bag to three per customer. Similarly, the Louis Vuitton website limits online purchases to two of each style per customer, per calendar year.

With the American dollar weak, Europeans and Asians are flying in for deals and designers are worried about undercutting themselves, much as in 2000 and 2001 Gucci, Hermès and Vuitton shops in Paris put bag limits on Asian shoppers, leading to surreal scenes of Asian customers on the Champs-Élysées soliciting Western tourists to buy bags for them. And with American handbag sales growth slowing this year (perhaps there’s no more room in those New York closets), the handbag phenomenon has not only become world wide, it is now fuelled by growth in emergingmarket countries.

Handbags are weird, almost mystical. There are hundreds of websites devoted to bags, that treat the bags themselves as living celebrities, and they have some of the highest drooling density on the internet. On thebagforum.com, for example, there are 606 active threads devoted to Louis Vuitton bags, nearly ten thousand posts just about this one bag designer, with an average incidence of 0.837 “oh my god” or “to die for” comments per posting. The website is set up so you first introduce yourself, then “show off your bag,” then write OMG or TDF about someone else’s bag.

And it’s not just quantity. A few years ago, the Boston fashion press reported that Elizabeth Hurley had been seen club-hopping around London with a Che-embroidered Louis Vuitton bag. She may well have been under contract to be seen with that bag, but one has to ask: Che on a designer handbag? Sure, Che was an interesting guy, sure Alberto Korda’s iconic picture of him was called “the most famous photograph in the world” by the Maryland Institute of Art, but whether you love him or hate him, Che just doesn’t make sense on a Vuitton bag. Fans would point out that he was a Marxist fundamentally opposed to the fetishization of commodities. Detractors would mention that at La Cabana he executed several thousand of exactly the sort of people who’d be most likely to shell out several thousand for a handbag. Lawyers would point out that Korda was never paid for the intellectual property rights of the photograph. And even those who are neither fans, nor detractors, nor lawyers, who simply admire his picture as a countercultural symbol, must get a bit of cognitive dissonance when that symbol is on the most bourgeois of bags. No?

But instead of being slowed down by this sort of dissonance, handbag designers have used it to fight off staleness in brands available on every streetcorner. Once this was done through Hollywood stars, but as those sorts of endorsements have become too common, designers have sought out new territory. “To be perceived as cutting edge, designers must make use of a different kind of celebrity,” says Elizabeth Currid, author of The Warhol Economy: How Fashion, Art and Music Drive New York City. “They need an art star.”

Accordingly, they have sought to blend brands with artists like Eliasson, Sprouse, Wilson, Beecroft, Murakami and Richard Prince (for Vuitton), Koons and Sachs (Fendi), Hirst (Levis and shoe designer Manolo Blahnik), Tracey Emin (Longchamp) and many others. And in the jungle of all these brands, Louis Vuitton stands out as a genius of the modern world, the 500-pound gorilla of handbags, combining designs that are both timeless and edgy with a nearly prescient sense of the international flow of image and information.

Olafur Eliasson kept out of the bags themselves, designing centerpieces for Vuitton’s Christmas shop-windows, lamps shaped like an eye looking back out at the customer with a mirror in the center, with the promise to “put the consumer in the spotlight.” Somehow Eliasson seems a fitting collaboration—his work is always beautiful and always bland, the sort of artist that the wives of hedge fund managers can appreciate.

By far the most successful collaboration, for both Vuitton and the artist, was the 2003 © MURAKAMI show at the Los Angeles MOCA. In that year alone, the collaboration brought in $300 million and shook up Vuitton’s reputation just as it was becoming staid. And it turned Takashi Murakami, previously unknown beyond art circles, into a celebrity.

The MOCA show drew particular media attention because it integrated a functioning boutique into the exhibition as an “installation.” There was a store in the gallery where viewers could buy the Murakami-Vuitton bags. And they did, by the thousands, with thousands more on waiting lists.

“One of the most radical aspects of Murakami’s work is his willingness both to embrace and exploit the idea of his brand, to mingle his identity with a corporate identity and play with that,” said Paul Schimmel, MOCA’s chief curator. A less generous person might respond that there is nothing so radical about the artist’s shameless self-advertising, though for MOCA itself the step did push boundaries. As a nonprofit institution, its only benefit was massively higher ticket sales, and an opening party with Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, etc. More people will pay to get into a museum showing handbags than one showing art.

This year, the Murakami-Vuitton collaboration moved to the Brooklyn Museum, which included not only a Vuitton store, but also a surreal performance of African immigrant vendors selling “fake” Vuitton bags from blankets on the sidewalk, except here the fakes were clearly real and cost accordingly. “I always want the art to be accessible,” explained Murakami, who employs over a hundred assembly-line artists to manufacture everything from paintings to keyrings. “The money embarrasses me.” And if you believe that, I have a bridge for sale.

Murakami is sort of like an oversweet jelly doughnut. Tasty at the time, but with a sickly aftertaste. He created a buzz, sold a lot of product, but ended up reinforcing the mainstream-ness of the brand. So this year Vuitton also tried an edgier artist. Richard Prince’s “Big City After Dark” line of Vuitton bags was unveiled this spring at the Guggenheim Museum as Prince’s exhibition of paintings and photographs was wrapping up.

Prince is a far better artist than Murakami, one who’s not going to simply take the opportunity to smear himself all over Vuitton. Instead, he made bags that deliberately look like Chinese fakes. Handbags are the cash-cows of the big designers, and the distinction between real and fake is the most fundamental pillar of the fashion industry. Just last year Vuitton’s “special teams” launched over 13,000 lawsuits and 6,000 raids leading to the arrest of over a thousand counterfeiters. By attacking this distinction between real and fake, Prince actually did something interesting with a handbag.

Prince kept his soul, the Chinese counterfeiters benefit as fashionistas find that they can take the art one step further by buying a real fake bag instead of a fake fake (real) bag, and Vuitton, well, if Vuitton can use Che it can use a line of candy-colored bags nobody wants in order to keep itself ahead of the curve. (Though I don’t understand why the fashion public reacted poorly to Vuitton’s Prince line; even on a purely aesthetic level I find them to be the most appealing bags I’ve seen by any designer.) They won’t sell like Murakami and that is a break with the rules of fashion—designers are willing to make dresses nobody will buy, but their real cash comes from bags, sunglasses and perfumes—but it will revitalize the brand and make the rest of its inventory more vibrant. Even for Vuitton, the real measure of success in the Prince line will not be how many Prince bags it sells. It will be how many real fakes the Chinese counterfeiters sell.

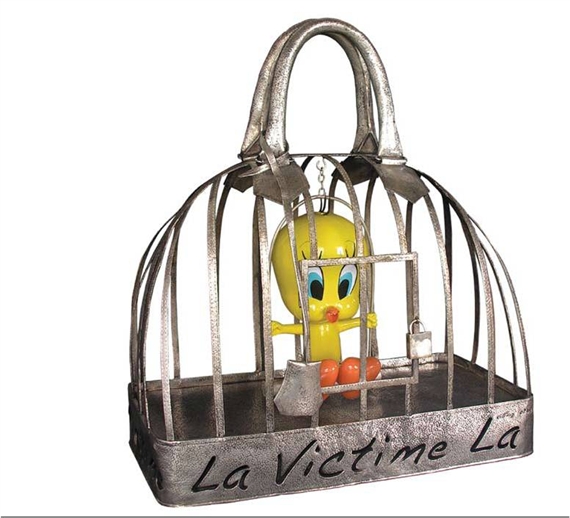

The whole point, of course, is branding. When the established Indonesian artist Astari poked fun at the LV brand by making metal handbags with the words “La Victime” or “Love Void” on them, Vuitton’s good-humored response was to purchase the bags. But when the relatively unknown Nadia Plesner used a Louis Vuittonesque purse in a piece showing a starving Darfur child, Vuitton sued. The fact that Plesner donates all proceeds to the foundation Divest for Darfur, that she didn’t use their trademark, that the work was parody, was all irrelevant for Vuitton’s lawyers, who found a jurisdiction where they could wield the simple threat of the lawsuit as a club. The details are also irrelevant for many Vuitton bag lovers. This is a typical post from thebagforum.com: “I think its an awful vision to put a third world starving child in the same photo as a luxury handbag. I hope she (the artist) loses the suit. I’d be pissed if I were Louis Vuitton as well!!! What an insult!”

But the poster is not really worried about the insult to Vuitton. She’s worried about the insult to herself. She owns a Vuitton bag, and puts her identity inside. She doesn’t want to think of herself as a shallow bourgeois (ergo, Che-themed luxury goods). But here’s the funny thing about using conspicuous consumption to mark your social status: A bag that costs between $1000 and $10,000 might signal personal wealth, but it’s also a sign that you belong to a relatively poor social group.

The term conspicuous consumption comes from Thorstein Veblen, who in 1899 argued that people buy expensive goods to prove they are prosperous. This meme has endured, but it’s only partially right. Visible luxury, it turns out, is defensive. Instead of positively proving prosperity, it’s a way to fight off the negative perception that the owner is poor.

In Conspicuous Consumption and Race, economists Kerwin Kofi Charles, Erik Hurst and Nikolai Roussanov studied why traditionally poorer ethnic groups spend a significantly higher percentage of their income on “bling” goods that advertise wealth—cars, jewellery, clothes, and, of course, handbags. They discovered that regardless of race or culture, rich people in poor peer groups spend a significantly higher percentage of their incomes on visible luxuries than equally rich people in rich groups. The ratio holds between Massachusetts and Mississippi, and between Norway and Nepal, and goes a long way to explaining why the handbag phenomenon has seen such an explosion recently in Asia.

Art travelled a similar path. The 17th century equivalent of bling was the portrait, intended for public display, in which sitters displayed their wealth and knowledge by having themselves painted surrounded by books, furniture, clothing, and even miniatures of all the paintings in their collections. But the true millionaires of today don’t spend their money conspicuously. The 8.4 million Americans whose net worth ranges between $1 million and $10 million, according to The Middle-Class Millionaire by Russ Alan Prince and Lewis Schiff, tend to buy only one visible luxury: high-performance cars. Otherwise, they spend their money on premiere health care, expensive vacations, and personal coaches for self-improvement.

Overall, the more established your wealth, the smaller the group to which you advertise it. If you really want to live like the Queen of England, don’t buy a handbag—Elizabeth’s bag, usually made by Launer London, holder of the Royal Warrant for handbags, is famous for being tiny and containing only a handkerchief, comb, lipstick and compact. Instead, buy a good bed with a $20,000 mattress. That’s real status. To die for. Oh my god. Want it bad…