Happy 30th

Lawndale Art Center just turned 30. The arts organization that was birthed in a sprawling, derelict, old warehouse/cable factory on Lawndale Avenue

Kelly Klaasmeyer / Houston Press

Sep 17, 2009

In a recent talk at Lawndale, founder James Surls described his role as director circa 1979. "I said yes to virtually everything that came in the door," he said. "Even if I thought it was the stupidest thing, I said, well, we could probably do that. We could take risks and take chances."

That spur-of-the-moment "Hey, kids, let's put on a show!" attitude is long gone. Anyone can submit a proposal, but proposals go through the spontaneity-free, formal review-and-approval process, which weeds out the possibility of any really spectacular failures. The sense of chaos in the original mission is not totally gone, though: The open-proposal method routinely results in exhibitions in the center's four galleries that are so eclectic, it looks like the organization suffers from multiple personality disorder.

Case in point: At the moment, from top to bottom, Lawndale is showing an otherworldly plaster spider-and-neon-filled installation by Romanian-born artist Adela Andea in the third-floor Project Space; a found-object and video installation about domestic discord by husband-and-wife artists Jahjehan Bath Ives and Joe Ives in the Mezzanine Gallery; and an Adrian Piper-inspired installation by Nathaniel Donnett with pointed human-behavior surveys and the artist's drawings in the downstairs gallery. A new "gallery" is also operating now. Snack Projects, a miniature exhibition space organized by artists Michael Guidry and Robert Ruello, hangs on the wall in Lawndale's entry. Bill Davenport's "Give One, Take One" is currently on view, a project in which people are invited to take and leave objects/art in the space. When I was there, a circular saw blade wrapped in orange tape was leaning against the back wall.

This grab-bag approach is unique in the state of Texas, and possibly the U.S. Lawndale isn't known for showing any one kind of art. It does not have a mission to advance any curatorial agenda, beyond being a direct reflection of Houston's art community. Artists can propose solo shows of their own work, and budding curators can put together and propose group shows. Lawndale is open to it all.

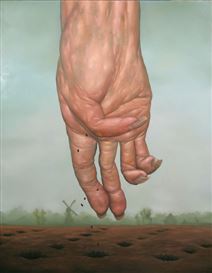

The closest Lawndale gets to curating its own shows is asking someone to put something together for a special event, such as the current "30th Anniversary Exhibition," curated by Clint Willour of the Galveston Arts Center. For the show, Willour selected work from six artists who have exhibited at Lawndale in the last five years. Seth Alverson's paintings, which are figurative but painted with a realism as unsettling as their subject matter, steal the show.

The paintings are grouped together diabolically. One depicts the bent-over butt of a woman in running shorts, each dimple of cellulite on her pale legs exactly modeled. In the artist's nearby painting of an upholstered brown velveteen armchair, the soft fabric is rendered with a sheen that mimics the tufted flesh of the woman's legs. In between the chair and butt images is a canvas depicting a pair of hefty, less-than-pert breasts propped on a windowsill. There are also portraits, both of chubby girls, one seemingly painted from a class photo of a smiling Pentecostal student, the other depicting a big, surly-looking girl with her arms crossed, looking like she's just waiting to kick your ass in dodge ball. The Gerhard Richter-like smudged paint of her face is especially ominous.

The work doesn't come off as mean or sexist as it may sound. Alverson is presenting a fleshy, critical mass of awkwardness. The dialogue between the artworks is really strange, but it's incredibly powerful. There's other good work in the show, but these paintings are worth the trip on their own. Alverson is wrapping up grad school now at Virginia Commonwealth University. Lawndale gave him his first big solo show with "Thunderdome" in 2006.

Today Lawndale is a 501(c)3 nonprofit with accountability to boards, granting organizations and the IRS. It's solvent enough to put on 25 shows a year and run a residency program that provides studio space and stipends to artists. The grown-up Lawndale is no longer an edgy renegade with nothing to lose. But while it's a great accomplishment to come up from nothing and become a responsible, legitimate, bill-paying entity, a pillar of the arts community, that doesn't mean Houstonians don't wax nostalgic over Lawndale's lost youth.

That nostalgia was out in force for Surls's lecture. The Houston art community and Lawndale alums came in droves. The story of Lawndale's birth and early years is well known to many, but attendees seemed eager to hear it again from the man who started it all. The story of Lawndale is a creation myth that for many defines Houston's art community. Sitting in Lawndale's packed main gallery as Surls recounted Lawndale anecdotes was like crouching around a fire and listening to a tribal elder explain the origins of his people.

For the uninitiated, Lawndale began at the University of Houston when a fire damaged the university's art studios. The painters and sculptors had to be relocated, so the administration apologetically offered Surls, the sculpture instructor, an old warehouse on Lawndale for his students.

The Lawndale space became available at the perfect time. As Surls recalled, the arts community was upset with the Museum of Fine Arts and its director, William C. Agee, who "really had a reputation of not showing local artists." Surls said Houston needed a site for trial-and-error experimentation, "a laboratory for young artists."

There wasn't a budget for the warehouse space. "Students literally painted the floors, they painted the walls. They mopped the place, they lit the place, they did everything," said Surls. Other support came from the community and university, both wittingly and unwittingly. For one show, Lawndale needed some pedestals, so Surls sent some students over to talk to William Robinson, then-颅director of UH's Blaffer Gallery. "They came back like in 20 minutes with a pickup full of pedestals. I said, 'Man, that's great! He's really generous,'" recalled Surls. "Well, they didn't ask Bill. They just went over and got them."

Despite the lack of budget, Surls, along with his students and other Houston artists, put together exhibitions and performances pretty much by any means necessary, from the epic "Pow Wow" show with work by more than 500 artists, to the legendary, police-raided Black Flag concert that almost got Lawndale shut down. Surls moved on in 1982, burnt out after a frenetic three years (and having spent thousands on Lawndale from his own pocket). Others took up the torch, and Lawndale became a nonprofit in 1989, moving to its current space in 1992.

The Lawndale "creation myth" speaks to the Houston art community's sense of self -- raw, do-it-yourself, unbeholden. In 2009, Houston's art scene is definitely on the national and international radar, but it isn't a city that draws calculating careerists. Artists are still taking the initiative and starting their own spaces. Box 13, Skydive, Optical Project and the Johanna Gallery are several recent examples. Cheap raw warehouse space isn't available like it was 30 years ago, but artists are resourceful. Box 13 is located in an old storefront on Harrisburg, and the Johanna and Optical Project operate out of their founders' homes. Skydive is housed in cheap office space in a down-at-the heels building on Montrose. In 30 years, people will be reminiscing about these places, and maybe some of them will still be around. It's a good bet Lawndale will be.

COPYRIGHT: Copyright NT Media, LLC Sep 17, 2009. Provided by Proquest- CSA, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Only fair use as provided by the United States copyright law is permitted.

PROQUEST-CSA, LLC- MAKES NO WARRANTY REGARDING THE ACCURACY, COMPLETENESS, OR TIMELINESS OF THE LICENSED MATERIALS OR ANY WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.