Making The Met: The 150th-Anniversary Exhibition and the Serendipitous Saint Rosalia

The postponed retrospective of the largest museum in the United States finally opened and leads the visitor through ten galleries, each dedicated to a different era of its history. One painting became especially relevant with recent developments

Maya Garabedian / 黑料不打烊

Sep 02, 2020

The postponed retrospective of the largest museum in the United States finally opened and leads the visitor through ten galleries, each dedicated to a different era of its history. One painting became especially relevant with recent developments.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Paintings Galleries photograph, mother and children in front of Emanuel Leutze’s George Washington Crossing the Delaware, taken July 10, 1905. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the wake of a global health crisis, since February museums were forced to close their doors for the sake of everyone’s safety. This meant that one of the most important exhibitions of the year was unable to launch at its scheduled time, but is now finally open to the public. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was originally set to hold their 150th-anniversary exhibition, Making The Met from March 30 until August 2. After months of uncertainty, the exhibition has now opened and is running through January 3, 2021, and one painting in particular will seem even more miraculous in its new context.

Making The Met has over 250 works of art, from world-renowned favorites to delicate artifacts, spanning the period in its entirety. Beyond the works themselves, the exhibition’s layout is incredibly unique, organized around the transformational moments in the museum’s personal history, and its positioning in the context of world history. Guided by the evolution of the museum’s collection, buildings, ambitions, and inspirations over the years, the ten chronological sections are centered around “The Street,” a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse into the museum’s past via archival photographs, animated history, and stories of community outreach.

Antonio Rossellio, Madonna and Child with Angels, ca. 1455-60, marble with gilt details on halo and dress. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The first gallery, “The Founding Decades,” allows visitors to travel through time to where it all began in 1870, back when The Met was founded simply as a concept — no art, no building, and no professional staff. It houses early acquisitions like antiques excavated from Cyprus, Toltec reliefs, Japanese armor, and of course, European oil paintings. “Art for All,” the second gallery, is a reminder of The Met’s attempt to reach an audience beyond the traditional elites, like designers, craftspeople, and students in the early 20th century. The Met began to expand their definition of high art by including more ephemeral and utilitarian objects during this time, making musical instruments, textiles, and prints and drawings the three highlighted collections in “Art for All.” During this same era, however, the museum began to aspire to the model of collections like that of European royalty and aristocracy. “Princely Aspirations” features objects prized for their one-of-a-kind beauty, given to the museum by tycoons of the Gilded Age.

Paul Revere Jr., Teapot, 1796, silver with wooden handle. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Since 1906, The Met has sponsored excavations, beginning in Egypt and extending throughout the Middle East, collecting objects from ancient civilizations. The fourth gallery, “Collecting through Excavation” concentrates on the findings from the 1920s and 1930s, a time when a policy of partage allowed the museum to keep a portion of the archaeological findings. The centerpiece is a statue of Hatshepsut, one of the most successful female rulers of ancient Egypt. Switching from global to national history, the subsequent gallery, “Creating a National Narrative,” focuses on the years leading up to the opening of the American Wing in 1924, creating a visual definition of what it meant to be American during the height of European immigration. The following gallery, “Visions of Collecting,” melds global and national perspectives, highlights some 2,000 objects given to the museum in 1929, introducing new diversity of American, European, Asian, and Islamic Art into the museum.

Artist unknown, Seated Statue of Hatshepsut, ca. 1479-1458 B.C., indurated limestone and paint. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

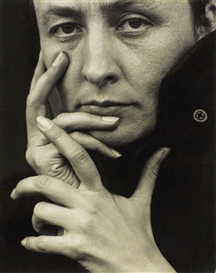

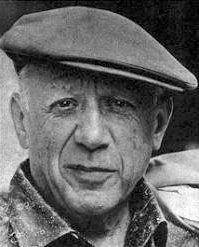

Continuing to put a spotlight on how formative the 1920s and 1930s were for The Met, the gallery, “Reckoning with Modernism,” is a product of the museum embarking on a new program at the time, prioritizing contemporary art and design. It features the tremendous gifts that helped shape The Met’s modern collections, featuring works by Pablo Picasso, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann — their emphases on individuality starkly contrasting the following gallery, “Fragmented Histories,” which focuses on the impact of World War II. Heaviness is replaced with buoyant vibrancy in the remaining two galleries. “The Centennial” is a nod to The Met’s centennial exhibition in 1970, where the museum celebrated its past, present, and future, vowing to make a greater commitment to non-Western and contemporary art. This time, there are installations of Islamic Art, the arts of Africa, Oceania, the Americas, Asian Art, and 20th century art. The exhibition culminates in “Broadening Perspectives,” displaying acquisitions from the last three decades, aligning with their mission of expanding the global reach of the collection and even including categories of art that previous generations have overlooked.

Georgia O’Keeffe, From the Faraway Nearby, 1937, oil painting on canvas. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Perhaps the most fascinating in the context of today’s society, is one of The Met’s first purchases in “The Founding Decades.” In an ironic coincidence, given the fact most of the world has been in some form of quarantine over the last months, one of the most beautiful pieces in Making The Met is Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-stricken of Palermo, was painted by Anthony van Dyck while he was in quarantine. In 1624, 25-year-old Anthony van Dyck traveled from his hometown of Antwerp, Belgium, to Palermo, Sicily, after he was commissioned by Sicily’s Spanish viceroy for a portrait. As the plague struck Palermo, the viceroy declared a state of emergency, forcing everyone into quarantine. Within weeks, the viceroy van Dyck had painted, the only person he knew on the island, was killed from the disease. The city’s gate closed, and the port was shut down, leaving van Dyck no choice but to bear witness to the divine intervention that ensued.

Anthony van Dyck, Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-stricken of Palermo, 1624, oil painting on canvas. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

One day, a local man had a vision of a woman, who he believed to be Saint Rosalia (the Italian translation of the name Rosalie), and claimed she had instructed him to search for her remains. The man, with a group of Franciscan friars, began digging in the grotto on Monte Pellegrino where she was said to have spent the end of her life. Her bones were discovered alongside a transcription she wrote into the cave’s wall, and her remains were paraded through the streets. Miraculously, the plague ended shortly thereafter. Saint Rosalia was credited with ending the people’s suffering, and from then on, was regarded as the patron saint of Palermo. Van Dyck took a half-finished self-portrait he had been painting and completely started over, depicting instead, the miraculous Saint Rosalia floating over the town, parting the dark haze to ascend into the sky. In light of recent events, residents of Palermo have begun praying to Saint Rosalia to protect them once again.

The 150th-anniversary exhibition, Making The Met, is a must-see, with ten beautiful chronologically-ordered galleries and a once-in-a-lifetime glimpse at the museum’s inner workings, both past and present. After the long wait, Making The Met has finally opened its doors, and Saint Rosalia is there to greet you.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page