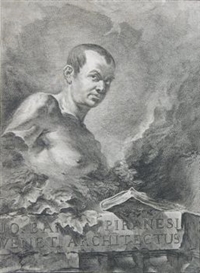

Piranesi's Infernal Prisons

Piranesi鈥檚 Imaginary Prisons depict vast, oppressive architectures of suffering, blending classical ruins with industrial horrors, evoking themes of power, control, and the sublime

Michael Pearce / 黑料不打烊

Apr 02, 2025

Giambattista Piranesi published his Carceri d'invenzione (Imaginary Prisons) in two editions, first as a series of fourteen etchings which he modified for a superior and darker second edition of sixteen prints, which was published in 1761. In the second edition the relatively simple architecture of the first was embellished with richly layered surfaces of machinery and loose encrustations of ill-defined texture, opening the imagination of viewers to visions of torture and demonic punishment.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Le Carceri d'Invenzione, plate 2 - Second Edition, 1761.

Piranesi’s sublime fantasies did not emerge from nothing – he followed a tradition of dramatic backdrop designers who rendered beautifully observed perspective drawings as the settings for operas and plays on the illusory stages of the theatre, including Antonio Galli Bibiena, who preceded Piranesi with drawings of imaginary prisons while a courtier to Charles VI, the Holy Roman Emperor, including one set in a royal palace. Bibiena served as His Majesty's First Theatrical Engineer, a position of prestige and creative potential, and designed settings for the Vienna state opera and the Dresden Opera House.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Le Carceri d'Invenzione, plate 6 - Second Edition, 1761.

But while earlier theatrical fantasies of prisons were oppressive stone buildings of gravity and weight, Piranesi fantasized cruel industrial factory dungeons built for impersonal punishment on a vast scale, where infernal machines ground flesh and torture never stopped. Vast expanses of the architecture of hellish oppression were thrust upward in monstrous arches of stone, built over the smashed ruins of ancient civilizations. Trained as an architectural illustrator, Piranesi played with perspective to create impossibly elevated chambers and arcades extending high above the viewer. And if the sublime heights of this terrifying underworld were impressive, Piranesi implied even greater depths were concealed deeper beneath the horrific excavations of his dungeons of damnation, as figures beckoned from subterranean tombs concealed beneath wrecked masonry and battered friezes. Thick shipyard cables hung from gigantic pulleys and sharp spikes embedded into immense beams threatened impalement. High on a filthy ledge, a bound prisoner wailed, tied to the height by massive chains looped from iron hoops embedded in dark vaults. A torturer hauled on a giant spindle racking the bound body of a doomed captive, threatened by another dart-wielding tormentor. De Quincey imagined Piranesi climbing in the impossible heights, lost in the eternal and impossible corridors of his opiated underworld. Hopeless victims of the infernal machines were ground beneath massive cogs and wheels, but Piranesi’s genius was for suggestion, not explicit gore, and vivid imagination did most of the work of pulling demonic suffering from the shadows, for the obscurity of gloom amplified the horror – the violence a distant performance for sensation-hungry crowds of anonymous spectators who filled catwalks far above the killing floor.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Le Carceri d'Invenzione, plate 7 - Second Edition, 1761.

The irrational spaces of the vaulted prisons offered no opportunity for escape. Staircases swooped over the eternal dungeons flying upward wrapping cylindrical towers capped by balustrades and supporting arches raised over vast voids of subterranean space – these caverns of monstrous architecture furnished with the hopeless equipment of everlasting torture. Dense layers of bridges and vaults piled over each other in receding perspective, creating unthinkable depths housing an industry of suffering, these sublime caverns concealing a factory for fear. A vast cathedral thurible hung motionless from the keystone of an immeasurable arch, the heavenly smoke of holy incense extinguished, the iron scent of blood in its place.

Piranesi combined the classical architecture of ruined Rome with the factory shipyards of the Arsenal of his native Venice where tens of thousands of artisans cranked out a ship each day from prefabricated kits of oaken frames. There, the fortified entrance to the dock was guarded by monumental lions seized from the Greeks, and sculptures frozen in the still and elegant poses of classical poise, while behind the battlements and ramparts secret factories constructed baroque weapons of explosive destruction. Piranesi reimagined the machines and architecture of mass-production concealed in underground caverns, festooned in giant chains pre-figuring the achievements of early industry and the broad hawsers of the fleet suspended from woodblock pulleys dressing the encrusted equipment of his hellish dungeons, and his prisons were visionary fantasies of the guard towers and wet walls of the Arsenal docks extended upward, bridged by the frames of strange scaffolds and bridges sunk deep beneath the earth. In Rome, he became intimate with the ruins of the eternal city, and an expert in the collapsing and decayed architecture of the empire.

.Jpeg)

Pope Benedict XIV’s efforts to modernize Rome under the guise of a revival of decorative neo-classical architecture did little to disguise the corruption of the clergy, or to challenge the pragmatic faithlessness of the Enlightenment. As the leisured nobility and the burgeoning middle class of the 18th century learned the new thought, their imaginations were opened to visions of the world stretching far beyond the conventions of the church and freed from the power of religion. Artists had begun to envision stories and actions in previously forbidden spaces – the interplanetary fantasies of Cyrano de Bergerac of 1657 opened the fantastic boundaries of scientific investigation into speculative fantasy, and although the murderously libertine excesses of the Marquis de Sade lay ahead in the 19th century, a new and indulgent approach to sensuality and decadence emerged in the eighteenth – Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon's Strayings of the Heart and Mind, and The Sofa gave voyeuristic details about the intimate adventures of men and women freed from conventional morality, and readers were intrigued by the provocative symbolism of The Indiscreet Jewels, and by the bold transgressions depicted in Jean-Charles de Latouche's Histoire de Dom Bougre, Portier des Chartreux. In Therese the Philosopher, the eponymous heroine willingly submitted to her Jesuit teacher, who conflated religious ecstasy with physical pleasure.

Piranesi’s architectural capricci seduced viewers like the clandestine readers of such transgressive stories – these ruins of the classical world, these borrowed vaults of cathedral stone, these prisons of the mind, were doorways to amoral fantasies of suffering, predictive precursors to the mass-destruction of 19th century industrial war, the death-camps of the twentieth, and the secretive prisons of the twenty-first. Piranesi seemed to bear the burden of depravity with him, conscious of the consequences of the dying religious tradition, of the consequences of abandoning the ethics of two millennia of Christian thought. There was no escape from the depths of his prisons, no hope for the condemned, fated only to suffer. No judgement was going to rescue the prisoners from their doom. They were the damned of Dante’s Inferno, enacting a theatre of torture for the guided figures of the anonymous crowds perched high above on the inexplicable catwalks and suspended bridges floating impossibly in the distant vaults. Did Virgil guide Dante through Piranesi’s prisons? Pairs of dark figures seemed to observe the machines and confer on the performances. As the sequence of the series developed, Piranesi carried his audience downward as his point of view collapsed beneath the gravity of his prisons, shifting from the vertical compositions of the tall first half to the weight of the horizontal landscapes of the second, grinding the point of view downward to a worm’s eye positioned in the slime of the dungeon’s floor. The last images were drawn with an increasingly uneven angle to the eyeline, as if he had succumbed – dragging his audience with him – into the subterranean burden of oppression. In the 16th plate, Piranesi seemed to memorialize himself on a central monumental tombstone inscribed with deeply cut Latin words reading impietati et malis artisus – an artist of impiety and evil.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

.Jpeg)