The Art Gallery's Being Mean to Me

I`m not much of a film critic. But when I was invited to last night`s premiere of a new HBO documentary, I accepted because the subject of the film

Edward Winkleman / Edward Winkleman

Jun 18, 2008

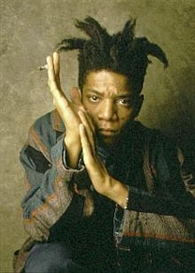

The Art of Failure: Chuck Connelly Not for Sale is the unusual story of the rise and fall of a major talent, along with Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat, from the 1980s art world. Though he was extremely talented with a profitable collection of work, Chuck Connelly ended up alienating every collector and gallery owner he worked with. This 63-minute documentary follows the life of this brilliant yet enigmatic painter, who had great success as a young artist but who now sees his career fading. Driven by desperation, and left by his wife during the course of this documentary, Connelly hires an actor to pose as a young, upcoming artist to sell Chuck`s work to galleries and art dealers. The film provides an intimate and often troubling character study of Connelly, a working-class guy from Pittsburgh who holds "traditional" beliefs that art is, above all, about personal expression and craftsmanship. These notions have proven to be less-than-fashionable in today`s elite art world, the inner workings of which are also glimpsed in the film. Shot over six years, this dramatic and entertaining documentary explores a painter`s passion for his work, despite being his own worst enemy.

Describing The Art of Failure: Chuck Connelly Not for Sale, director Jeff Stimmel notes, "This is a simple story of a working-class outsider who is fighting ageism, elitism, and cronyism - in this case within the art world." In the film, Connelly vocally rails against what he sees as profit-hungry tactics of dealers and gallery owners, who buy paintings in bulk to get the greatest return on their investment. With over 3,000 paintings in storage, Connelly could be paid a large sum to clear out his studio and sell his entire collection of artwork. Though this would make him rich, Connelly would never agree to sell in bulk because each individual painting would be priced "dirt cheap."

Interestingly, in 1989 Martin Scorsese was looking for an artist who could be a model for his film, New York Stories: Life Lessons. Several art dealers recommended Connelly. Subsequently, the "wild man artist" played by Nick Nolte was based on Chuck, and all of the artwork shown in the film was Connelly`s.

A number of insiders in the art world are interviewed in the film, including the venerable gallery owner Annina Nosei, who launched both Chuck`s career and those of Basquiat and Schnabel; the successful 1980s artist Mark Kostabi, who is the very opposite of Chuck; Walter Robinson, editor of ArtNet, who provides astute insights into Connelly`s art; Matt Garfield, Chuck`s patron, and others.

I actually enjoyed the film. There were plenty of comical moments and food for thought about careers in the art world. But I don`t think I can object enough to how this description frames the film for the viewer. I`m gonna try though:

Where to begin? I guess with the positive stuff. Of all the art world insiders interviewed, the one who stood head-and-shoulders above the rest in terms of not confirming some caricature (truly, his description of Connelly`s work was lovely) was Walter Robinson. Just about everyone else--perhaps through editing, perhaps through the questions they were asked, or perhaps through their own doing--was portrayed as a one-dimensional character.

Yes, that`s the positive stuff. My lingering impressions of what the director did (more what he missed) go down hill a bit from there.

Let`s start with this nonsense: "This is a simple story of a working-class outsider who is fighting ageism, elitism, and cronyism - in this case within the art world." "Working-class outsider"? Really? You mean like Warhol? Or de Kooning? or a thousand other starry-eyed youngsters who come to New York from working-class backgrounds across the country and the world and yet manage to learn how not to be their own worst enemy? The notion that the gallery system is oppressively classist is hogwash. I come from a working-class background, as do most of my friends who own galleries (granted, most of my friends who own galleries began in Williamsburg, but...) as do many of the artists I work with.

The film provides an intimate and often troubling character study of Connelly, a working-class guy from Pittsburgh who holds "traditional" beliefs that art is, above all, about personal expression and craftsmanship. These notions have proven to be less-than-fashionable in today`s elite art world, the inner workings of which are also glimpsed in the film.

I actually wish the director had lived up to this last claim. The "glimpse" of the inner workings of the art world is so thin as to be virtually translucent, revealing a bias behind it about how unfair the art world is that could have been easily put aside in the interest of objectivity.

For example, everyone I spoke to after the film was still confused about exactly why the galleries that worked with Connelly stopped working with him. The gallerists interviewed never got a chance to explain that. There`s the implication that once Page Six got a hold of Connelly`s quote about the Scorsese film (Chuck was quoted, although he was involved in the film, as saying "It sure wasn`t Raging Bull") that his career was instantly over, but no further explanation of why or how that comment ended his career. What "inner workings" exactly were at play there? Most dealers I know could spin such press into buckets of sales. Or would at least try. Why didn`t that happen here? We never find out.

I should note that I think Connelly is a very talented painter. Several times I gasped at works shown in the film. But this notion: "that art is, above all, about personal expression and craftsmanship" and $2 will get you a subway ride out to Flushing. In other words, why, if that`s all art is about, wouldn`t thousands of other artists out there deserve the same success Connelly feels was robbed from him? There are thousands of talented artists who will tell you that personal expression and craftsmanship are central to their work. Does the world have the means to celebrate them all? To make them all rich? Is that, "above all" what the world needs from its artists?

There`s a good deal of self-pity in the film. Connelly complains at one point "They tell you to be a rebel and then they tell you to kiss ass," without any sense at all that whoever "they" are, they have no role in telling you to be a "rebel." If you truly are a "rebel" you`ll refuse to kiss ass no matter who urges you to do so, which would seem to be what Connelly feels he`s doing. Which, admittedly, is admirable. But moments later he says "The art gallery`s being mean to me." (I think he was mocking some other artist, but the idea lingers that he too has been abused by the galleries.)

And here`s where I think both Connelly and Stimmel miss the point. Chuck insists on playing by his own rules. That`s great. But he goes one step further and more or less expects playing by his own rules to handsomely reward him. He admits he spent all the money he made in the 80s, just spent it up, and he wants more to keep coming in while he continues to party ferociously, offend people, screw those trying to help him, etc., etc.

I have repeatedly supported the notion that if artists are not happy with the terms of the system they have every right to change those terms. Implied in that opinion, though, is that the work of changing the terms falls to them. Not to the rest of the world. It`s no one else`s responsibility to change the system to meet your personal needs or preferences. There`s hard work involved in moving the world. If you`re not willing to do that work, then live with or work with the way it is. Sitting around bitching that it`s not designed to celebrate just you is sophomoric.

I will still highly recommend you check out this film. Again, the comical moments are priceless and the interviews offer plenty of valuable lessons. I do wish HBO wasn`t marketing it the way they are, though. Appealing to the public`s biases about how elitist the art world is is a cheap route toward attention, IMO.