The Ashcan Artists and Their Interstitial Spaces

Ashcan School artists depicted New York鈥檚 urban transitional spaces that blurred the lines between public and private life in the early 20th century

Kristen Osborne-Bartucca / 黑料不打烊

Apr 29, 2025

John Sloan, The Hairdresser’s Window, 1907, oil on canvas, 32 x 26 in. (81.3 x 66 cm).

In John Sloan’s Hairdresser’s Window, 1907, a woman with bleached blonde hair treats the hair of her seated client, whose back is to the viewer. The hairdresser is fully immersed in her work, which speaks for itself in the same way the advertisements plastered to the walls above and below her window advertise their wares. Sloan painted this from a real scene he’d come across in his frequent perambulations in the city, hoping to find “human incidents to etch and paint.” In the painting, passersby cannot help but gawk, which is understandable given the proximity of the women to the street below. Right at the edge of the window, with the client’s hair almost hanging out of it, the women are neither fully inside nor outside, and though they are not looking at the curious, judgmental crowd below, they no doubt know that they are on display.

Sloan and the other artists of the Ashcan School, a group of painters in the early 20th century committed to exploring their urban environment and rendering its reality onto the canvas, were fascinated by the multitude of spaces the city engendered. They painted the conspicuously public places such as crowded sidewalks and dockyards and parks and ferries and the Elevated, and they painted private, interior spaces such as theatres, apartments, restaurants, and boxing rings. And they also painted the spaces that were neither wholly public nor private – the threshold spaces, the interstitial spaces. On a rooftop, in a backyard, on a fire escape, at the aperture of a window, on a stoop, people could embrace the security that came from almost being “inside,” but also derive a degree of satisfaction from the knowledge that they were being visually consumed. In her seminal 1961 work On the Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs acknowledged the need for both privacy and visuality: “A good city street neighborhood achieves a marvel of balance between its people's determination to have essential privacy and their simultaneous wishes for differing degrees of contact, enjoyment or help from the people around.”

The rooftop, the fire escape, and the backyard were places where people living in crowded tenements could spill out into the open space to stretch their legs and feel a cool breeze. They were outside, but they were circumscribed, bounded. They were connected to the building that they called home, surrounded by neighbors known and unknown, straddling the line of visibility and invisibility. The rooftop exemplified these elements, having become more and more important as waves of immigrants stretched the tenement apartments to their breaking points. In 1929 the New York Times marveled at the rooftop phenomenon, calling it “a city above the city.” Sloan was the master of the rooftop scene, painting dozens of works that showed women doing laundry, drying their hair, and gossiping.

John Sloan, Red Kimono on the Roof, 1912, oil on canvas, 61 cm × 51 cm (24 in × 20 in).

The fact that it was mostly women, whether Sloan intended it to or not, speaks to the titillation of seeing and being seen in the city. In Red Kimono on the Roof, 1912, for example, the woman is dressed in a silken scarlet robe, connoting a bohemian lifestyle newly embraceable by women in the modern urban milieu. Though there is no one else present in the image, it is not hard to extrapolate from the brightness of the garment that some of her neighbors cannot help but watch her. Everett Shinn’s The Laundress, 1903, shows us a woman doing laundry in a tenement backyard, and even though there are no others visible, the viewer’s vantage point is likely from a tenement window, meaning that we are placed in the position of the urban watcher.

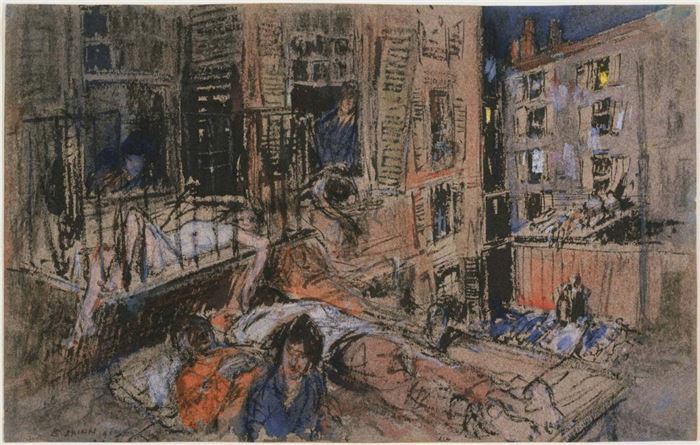

Everett Shinn’s Tenements at Hester Street, 1900, a work of ink and pastel on paper, depicts both rooftops and fire escapes. The work is a miserable, “squalid” scene (in the artist’s own words), showing ragged tenement dwellers seeking refuge from the heat out in the night air. But there is still an air of eroticism, as one young woman clad in only a white chemise is sprawled out provocatively on the fire escape. Similarly, Sloan’s Night Windows, 1910, features a scantily-clad young woman, who leans out her window, certainly cognizant of the fact that its brightness in the otherwise dark night would make her visible to her neighbors. Sloan derived this scene from one he must have seen in some variation numerous times in Greenwich Village: “a girl in dishabille at a window and a man on the roof smoking his pipe and taking in the charms while at a window below him his wife is busy hanging out the washed linen.”

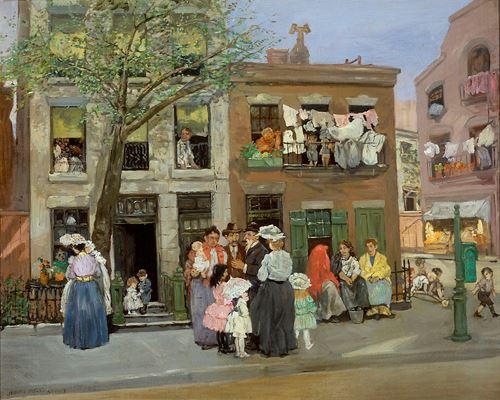

Jerome Myers, Sunday Morning, 1907, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 44 1/2 in. (95.3 x 113 cm).

Finally, the stoop was another site where city dwellers could remain tethered to the interior with its safety and familiarity, but also experience some of the sensory delights of the exterior world. Historian John G. Clark wrote in 1967 that “All of the world that needed seeing could be viewed from the stoop. It was a self-contained and self-sufficient world – a unity.” George Luks’ On the Steps, date unknown, depicts a man reading a newspaper, children gamboling, and women chatting and rocking babies, all on the steps; it shows the pragmatic need to spill out beyond the confines of the home. Jerome Myers’ scenes on the stoop also presented them as places to linger and look. In Lower New York, 1926, shows a woman with a baby standing on the top steps and a child the next building over perched in the middle, while above them the windows are filled with other residents taking in the steps and street below. Sunday Morning, 1907, features women hanging out of windows, relaxing on balconies, and conversing with each other on the stoop as children play and men pause in their walks to chat. The same elements are present in Theresa Ferber Bernstein’s Saturday Morning, Upper West Side, 1946, a colorful slice-of-life scene of New Yorkers moving seamlessly in their interstitial spaces.

And one of the most famous Ashcan works, George Bellows’ Cliff Dwellers, 1913, offers the same sort of city scene, albeit a more sprawling, crowded one. Here people not only congregate on the stoop but also linger in doorways and on balconies and out of windows, another permeable barrier between public and private. Ultimately in Bellows’ piece as well as the others discussed, there is almost no distinction between interior and exterior. It is in the interstitial spaces where, as Gaston Bachelard says in his 1958 Poetics of Space, “man’s being is confronted with the world’s being.”

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page