The Nude Tsunami

The just fight against sexual misbehavior, mainly performed by powerful men against women, didn’t stop at art, costing the traditional motif to be banished by association

Michael Pearce / ���ϲ�����

28 Sep, 2022

When earthquakes crack beneath the ocean, the breached seabed and the collapse of tectonic plates pass completely unnoticed by sea captains and sailors floating directly above the underwater cataclysm. Their serene ships glide over the temblor’s epicenter, oblivious to the massive movements deep beneath their keels. But the gargantuan shifts of earth’s sliding geology thrust incredible forces through the water, and as the displaced ocean swells away from the fault toward the rising continents, giant waves gradually climb to drown the land. Almost a quarter of million souls were lost when the violence of the hundred feet high Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 smashed into coastal towns, swept ships miles inland, and sucked floating houses out to sea.

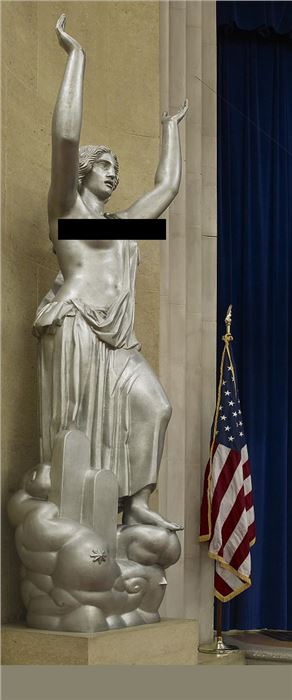

Spirit of Justice

In July of 1986, Attorney General Edwin Meese received his copy of the report of his Commission on Pornography in the Great Hall of the Justice Department. Unaccustomed to adulation, he was bemused by the sudden genuflection of delighted photojournalists, who threw themselves to the floor to capture images of the moment. Of course, the photographers had no desire to offer their service to him as liege lord – they were framing the perfect shot of the smiling legislator receiving the report while he stood in front of the bare-breasted statue of a semi-naked woman called The Spirit of Justice, which had decorated the room since 1933. The pictures caused laughter in the lofts and studios of American artists, who like mariners sailing over the underwater earthquake, had no idea that this was an early tremor, a warning of the full flush of the cancel-culture tsunami that was to begin in 1991. The Meese moment perfectly captured the tangling of fine art into legislation against sexism in the workplace. Except for a few outsider bohemian feminists, who had already started wearing gorilla masks and denounced museums for failing to show work by women in 1985, artists paid no attention.

Titian, Venus of Urbino

1991 was the year of the silent quake that was the epicenter for the tidal wave that would remove nudes from public galleries and begin an era of reaction against erotic images of the body. The first rumbles of the coming temblor that would raise up a tidal wave of social change had been felt as legislation was belatedly put in place against sexual harassment in March, when a Title IX lawsuit known as Robinson v. Jacksonville Shipyards was fought and won by a female welder against her employers who had tolerated male workers’ inappropriate displays of erotic pinups and graffiti in her workspace despite her complaints. After this suit, if nude or sexually provocative imagery had nothing to do with the work of employees, they could no longer be placed anywhere on any jobsite where workers might be confronted with them.

At the end of 1991, Anita Hill accused Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, and her complaint brought the routine workplace abuse of women into international news. These were major seismic cracks in the patriarchal seabed preventing the protection of women’s rights in the workplace.

Lucian Freud, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping

Bobbing about above the fault, artists still paid no attention, reasoning that their elitist art was immune from the vulgar issues of working-class girlie mags. But the folding crust creates a fault, a fault becomes a collapse, a collapse pushes the ocean’s mass toward the coast, and when the wave breaks, cities fall. Paintings and sculptures were soon caught up as targets in the anti-porn movement. To activists, the only things separating soft-porn centerfolds from many nude sculptures or nude paintings were technique and medium. Their subjects were otherwise indistinguishable, and consequently exhibiting paintings and sculptures of nudes could be construed as creating a hostile workplace by employees who objected to being compared to the naked flesh seen in such imagery, and argued that it metaphorically subjected them to the objectifying stares of colleagues. The nude retreated to private and domestic spaces and to museums and galleries where they were inseparable from the history of art.

A strange allegiance formed between radical feminists and conservative Christians. Feminists fulminated about eroticism and insisted that female nudes were offensive because of the exploitative male gaze. Religious conservatives complained righteously that representations of nudity were always sinful, inspiring deadly lust. The cancelling wave built in strength and the US government supported it. In September, Senator Jesse Helms put forward an amendment to a bill funding the National Endowment for the Arts that forbade the endowment from funding materials “that depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual or excretory activities or organs.” Congress passed the bill. Helms said, “From burning the American flag to desecrating one another's bodies, the depravity of these artists knows no bounds.” The legislation had an immediate and lethal effect upon art galleries and museums that received NEA grants, who now found themselves vulnerable to losing major funding for displaying any objects depicting the naked human body that might be construed as obscene.

Public figures tumbled in the tidal wave of opprobrium against sexual exploitation committed by the powerful. In 1998, Paula Jones sued President Bill Clinton for sexual harassment, and although her case was dismissed, Clinton was soon charged with having an inappropriate sexual relationship with Monica Lewinski, which resulted in his impeachment and subsequent acquittal. Angered by the hypocritical effort to impeach Clinton, pornographer Larry Flynt offered a million-dollar reward to anyone coming forward with information about the sexual misbehavior of Republican politicians. Soon, the extra-marital affairs of Bob Barr, Dan Burton, Helen Chenoweth-Hage, Newt Gingrich, Henry Hyde, Steven C. LaTourette, and Bob Livingston were revealed.

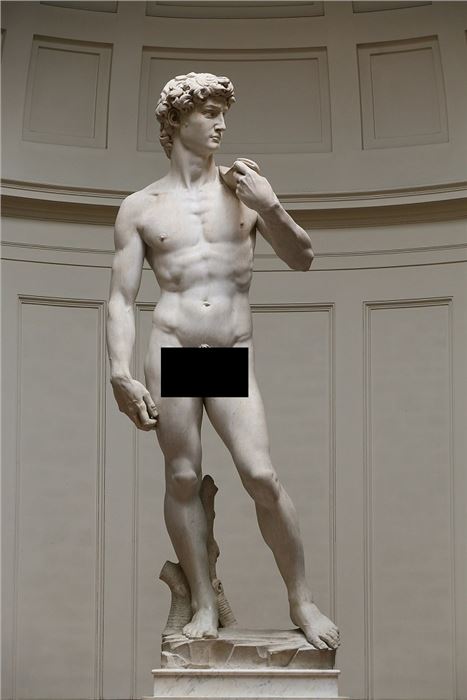

Michelangelo, David

In 2002 Attorney General John Ashcroft covered the The Spirit of Justice with blue drapery, ostensibly to provide a better photographic backdrop. Sex scandals continued in the aughties and teens. The iconic sweater-wearing dad, Hollywood sitcom comedian Bill Cosby was convicted as a repulsive serial rapist, and boner-boomer movie producer Harvey Weinstein was prosecuted as a lecherous exploiter of the women working in his films, including stars Angelina Jolie, Kate Beckinsale, and Gwyneth Paltrow. The vast wave of #metoo reckoning swept across the West. In Britain, disgusting pedophiles Gary Glitter, Jimmy Saville and a host of abusive BBC stars justly fell beneath it. Paintings of the nude were guilty by association.

In 2019 the covid lockdowns killed public art. Galleries everywhere closed, many permanently. Pictures of paintings of nudes could only find friends online. By now, the artists were paying attention. The painted nude has always stood in the awkward space where morals meet reality, and sensuality meets pornography. Pornography thrived online as people used it enthusiastically in their homes, but within the public coding and pixels of social media, activists argued that porn was always an assault on women that normalized violent attitudes toward them. Listening carefully, both Facebook and Instagram allowed anonymous complaints about image content to be made, and moderators deleted posts thought to be violations of their policies against pornography, punishing transgression by barring posters for weeks at a time. But, these moderators had only seconds to make a decision about whether or not content was distasteful, and despite Facebook’s own announcements that art was excused from their mousey censorship, many well-made realist paintings that included nudity were mistaken for erotic photography, and removed with consequential punishment, regardless of their posters’ innocence.

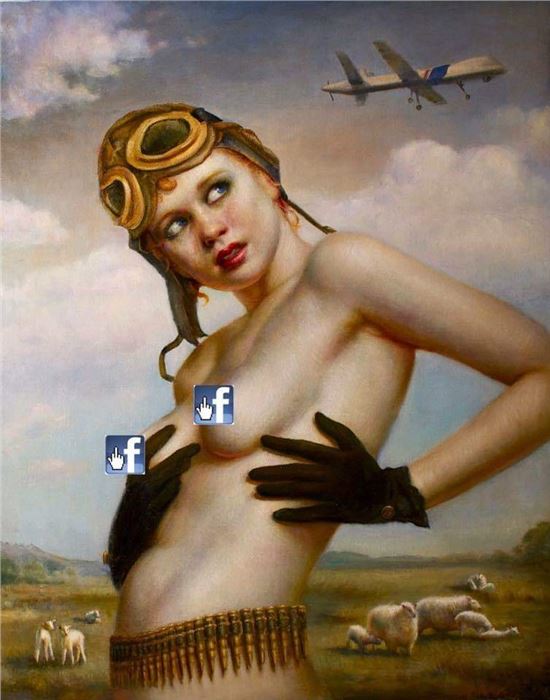

Rose Freymuth-Frazier, Uprising

Chagrined art lovers who fell afoul of these anonymous denunciations resorted to altering images of works of art with photoshopped blurring, digital pastie band-aids, and fig leaves covering all the naughty bits. Rose Freymuth-Frazier’s paintings of ironic 21st-century third-wave feminist pinups were censored by her social media platforms, so she began using cleverly altered versions of Facebook’s blue “like” thumbs-up icons to cover nipples and crotches in pictures of her paintings (she turned them into little middle-fingered salutes). But even with an attitude, self-censorship inevitably radiated an invisible aura of digital shame. Facebook allowed members of private groups to share paintings and sculptures of nude subjects, and these became digital ghettos of art appreciation, shielded from public scrutiny by agnostic walls built from binary algorithms.

Pandemic fear is winding down, and the galleries which survived the cruelties of the lockdowns are reopening. After the Spanish flu of 1918, which coincided with the end of the Great War, Western culture entered a period of licentious pleasure-seeking, as a new disillusioned generation abandoned the moral priorities of the old. Centers of libidinous decadence emerged in Europe and the Americas. Now, bolstered by a similar huge transference of wealth, and determined to please themselves after years of isolation, millennials and Gen-Z are partying hard – but there are no signs that paintings of nudes are among the priorities of their artists.

The tsunami swept nudes away.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS