The Sensual Beauty of Graham Toms’ Apocalypse

Myth, AI, and apocalyptic visions in surreal biomechanical worlds that reflect violence, spirituality, and a reimagining of art history

Michael Pearce / şÚÁϲ»´ňěČ

23 Sep, 2025

The Irish artist Graham Toms is redefining the boundaries of imaginative realism, expanding the range of its aesthetic by creating coherent fantasies of a swarming population of articulated and organic creatures. Built upon postmodern illogic and Acadian myths, he gives them the depth and breadth of narrative life, imagining a terrifying world overwhelmed by these mysteriously manufactured biomechanical entities – hybrids, part machine, and part insect. Blending sophisticated robotics with biology to form cybernetic physiology, these beings’ DNA has mutated and evolved into virulent forms which morph and over-run not only the landscapes of recent and ancient human history, but also revise and redirect the history of art. These are Gen-X paintings fed by the apocalyptic spirit of cyberpunk science fiction, comics, and the synthetic torrent of violent millenarian imagery that has cascaded with the tectonic power of a tidal wave over visual culture in the last seventy years as new media flooding the sphere of imagery once occupied by pigment, pencils, and plaster.

Toms’ venue is within the meeting-place of digital generation and analogue creation, between dreams and nightmares, and his imagery is new and unfamiliar, incorporating his own cartoon logic of structure, function, and motion with solid painterly craftsmanship. Toms has discovered the artistic grail. He has a unique approach and knows exactly what he is doing with it.

He thrusts his work into the narrative of art history. His brilliant, glowing Babylon of Necropolis reimagines Breughel’s Tower of Babel frighteningly re-erected and overrun in a machine city rethought from ancient forms and incorporated into the new civilization of these alien entities, the disembodied tower dematerializing and spirit rising into the grey heavens as the machines penetrate its windows and halls. The metaphor parallels our escaping technology, which programs itself, now. We are entering the frightening future described by prescient Iain Banks, who imagined a space-faring neo-communist Culture governed by artificial intelligences entrusted with universal economy and care for self-indulgent humans. The human figures appearing among Toms’ swarms have adapted to their situation, becoming glowing transhumanist reinventions of their antecedents – they are elongated and angelic, transfigured by DNA modifications, technological enhancements, and surgical improvements. They are more human than human, but already in the underworld. Toms’ Isle of the Dead emulates the great painting by Arnold Böcklin, where the island is the calm shore of death’s refuge, but in Toms’ version, the haven is paradoxically serene behind a writhing frame of insectoid and crawling creatures tumbling over each other in the foreground, a quiet center to the storm and alienation of artificial intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence, the Fairy Folk, and the Event Horizon

Although apocalyptic themes run through many of Toms’ paintings, there is a spiritual and ethereal quality that emerges in the compositions. He said Event Horizon “…alludes to what we might be in, in terms of artificial intelligence, the technology that’s revolutionizing our world right now. But there’s also our passed animals and pets, I have those in the world because there’s the idea of transformation, so although it’s multiverse, it’s not purely a material universe, there’s also what might be beyond the veil.” Toms’ paintings share ethereal parallels to 19th-century pictures of the fairy folk, but the tricksy beings inhabiting the otherworld of Toms’ invention are more honestly malevolent than any of Luis Falero’s creations which use other dimensional reality as an excuse for erotic fantasies, or the chaos and tumble of John Fitzgerald’s excursions which always end in whimsy, or the benevolent and childish crowds of Richard Doyle’s diminutive sidhe. There is a hidden world here, but the entities of Toms’ imagination are more plausible as highly evolved beings borne of the battlefield than as frivolous entities like the frolicking fairies of the Victorians – his hidden world is as much about mind as it is about the final frontier. Toms explained, “I’d been reading Hameroff and Penrose about consciousness and how to measure that in terms of the neurological activity of the human brain – it was as much about inner space as it was about outer space, which I found interesting.”

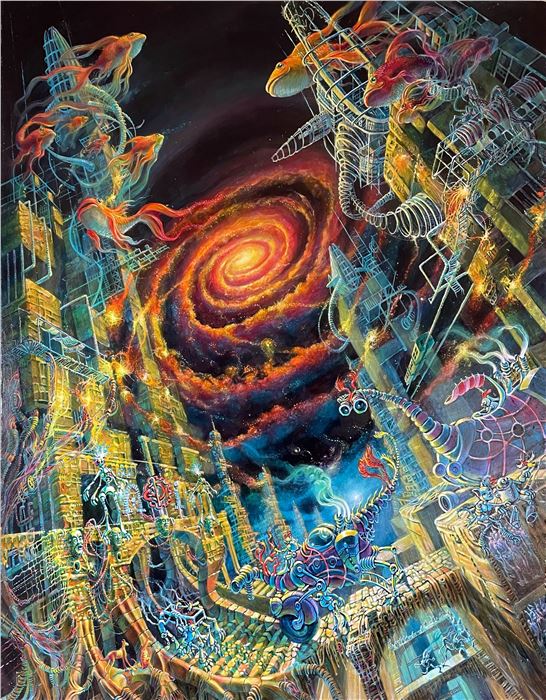

Graham Toms, Event Horizon, Acrylic on wooden panel, 60” x 66”

The organic machines are the distant descendants of AI weapons, programmed to overwhelm, and wired for self-improvement as mass-produced invasive entities driven by something resembling emergent self-awareness, a new kind of synthetic consciousness rising from computers programmed to program themselves with their original goals and intentions lost in their mysterious and artificial minds. He finds equal beauty in articulated skeletal forms as he does in koi fish and dragonflies – all abundantly tumbling over their targets, over-running and entering mankind’s machines, reimagining human history, revising living things in novel forms frighteningly resembling the original, these simulacra replacing reality with the fake.

Event Horizon is titled for the defining boundary around a black hole, setting the limit of proximity to the awesome destruction of unrestrained gravity, where even light cannot escape from the forces pulling everything to utter destruction. Beside the singularity, bizarre bots respond to the silent commands of their source code to preserve and replicate human civilization as best they can, regardless of their inevitable cosmic destiny, and there is beauty in their building.

Violence

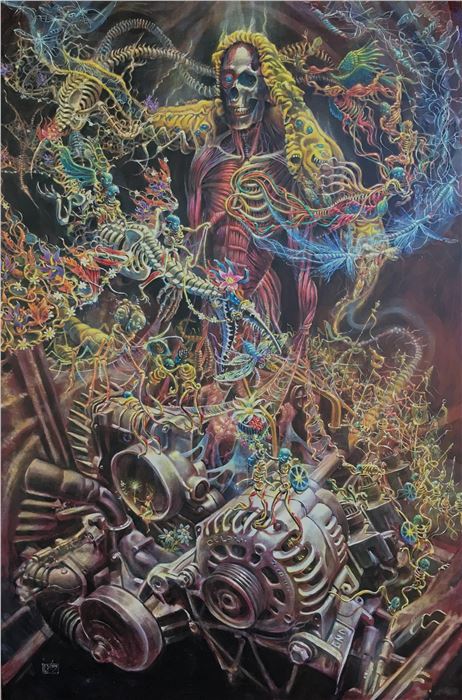

Though Toms enjoys apocalyptic imagery, his paintings are not a catalogue of gloom. Comedic robot creatures are scattered among the swarming machines. In the glowing city of light in Event Horizon machines are made cartoonish – two comical and gaping robots play with an automaton bird; a mechanical brontosaurus with bubble eyes driven by a chicken headed pilot lumbers across a stone bridge; floating four-armed robots like Sam Slade’s 2000AD Robohunter adversaries drift at the entrance to a high-towered ziggurat of masonry, microchips, and 3D printing. And though the looming figure of skeletal death spreads radiant and digitized fingers to inseminate the virus of alien and invasive intelligence into the big block power of Detroit steel in his Deity of Automobiles there is a hilarious little interlude of a blue-faced Mesopotamian robot master shaded by his servant stepping over the alternator.

Graham Toms, Deity of Automobiles, Acrylic on canvas, 60" x 40"

Toms attributes some of the recurring violence and the obsessive themes of his paintings to his youth in Northern Ireland and England. His father was a British Army soldier during the Troubles, and in his childhood and his student days Toms witnessed riots beginning, and bombings wrecking buildings. In 1972, he avoided being a victim of the twenty bombs of Bloody Friday only because his mother was late to the Oxford Street bus station, and on another occasion missed being killed by a roadside bomb by minutes, hearing soon afterward that a passer-by lost his leg in the blast. When his father moved his family to safety in England, Toms became accustomed to being a stranger in a strange land as an outsider Irish lad resented by the local people, and then, when he returned to Ireland, being an alien in his own country. He learned to swing his fists. Toms explained his attraction to violence, saying,

In some sense I relish it. It’s not that I’m pretending to be a victim of these things, either it’s part of, if you like, almost a participation. It’s probably why in my conversation with most nice people I’m always having to be guarded and careful, because I probably sound like a monster. For those closest to me it’s a little different, because then… you can feed your poison in small doses, and in that case it’s not such a shock, so yeah, you help them build up some immunity, because you can’t be constantly guarded, there has to be some “out” or I think it makes you mentally unhealthy, and so maybe the paintings are some sort of odd psychological exorcism, maybe a spiritual one too.

The violence is layered with complexity. In his carnivorous charcoal drawing of Demons Interrupting Grief, tangled dinosaurs battle for supremacy, with a beautifully modified beast dominating the foreground clad in Toms’ signature cybernetic modifications of blossoms and jeweled accretions and steered by a modified dog riding the luminous raptor. Toms’ wife Helen passed away this year, but she is at the heart of all his work, and even in the dinosaur battle of Toms’ night horrors, her spirit is there in the still calm and center of the tempest, where Toms, cast as an unmodified man, kneels at the feet of the glowing spirit of beauty, a celestial visitor from another realm bringing comfort to the downhearted, her faithful greyhounds Sonny and Drake as steadfast symbols of hope. There is peace in this storm.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS