A Mind Made of Silk

Many living beings interact with the world in complicated ways, with little reliance on their

brains. A big cerebellum or central nervous system doesn’t always equate to being the best

performer when it comes to nonhuman lifeforms. Spiders use their webs as silky extensions

of their minds, places to not only catch bugs but to solve problems and store memories. And

in reverse, the state of a spider’s nervous system has been proved to intensely affect its webbuilding capacities: dosed by scientists in the 1940s arachnids on amphetamines, LSD, and

caffeine spun of woozy, strung-out webs.

Octopuses are famously smart yet their neurons are mostly found in their arms, independent of

a main processing unit; their physical makeup of tentacles and thousands of suckers being far

too complex for central coordination. Some creatures offload what us humans see as part of the

mental apparatus and processes to outside of their neural system entirely: take grasshoppers

who have ears on their knees which

pre-parse information of where the nearest mate is screaming from. Take it a step further to the

hypothesis that certain information in a being’s genes is expressed outside, in the world, like

the case of birds nests as objects encoded into their genome, their expression varying from

species to species.

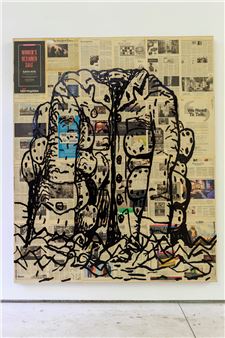

If cognitive tasks escape the above brains and sprawl into bodies—and in some cases into

the environment—what about us? Could it be conceivable that our ways of thinking and ways

of seeing extend beyond our corporeal limits to incorporate nonbiological components? Cave

drawings, hard drives, tapestries, buildings, coffee tables, paintings, the constructed world, the

natural world, the whole world. Where does the mind end and the world begin? No less than

a sea change perspective is required to even begin to see the invisible threads that sew this

neural tapestry together.

Recommended for you

Many living beings interact with the world in complicated ways, with little reliance on their

brains. A big cerebellum or central nervous system doesn’t always equate to being the best

performer when it comes to nonhuman lifeforms. Spiders use their webs as silky extensions

of their minds, places to not only catch bugs but to solve problems and store memories. And

in reverse, the state of a spider’s nervous system has been proved to intensely affect its webbuilding capacities: dosed by scientists in the 1940s arachnids on amphetamines, LSD, and

caffeine spun of woozy, strung-out webs.

Octopuses are famously smart yet their neurons are mostly found in their arms, independent of

a main processing unit; their physical makeup of tentacles and thousands of suckers being far

too complex for central coordination. Some creatures offload what us humans see as part of the

mental apparatus and processes to outside of their neural system entirely: take grasshoppers

who have ears on their knees which

pre-parse information of where the nearest mate is screaming from. Take it a step further to the

hypothesis that certain information in a being’s genes is expressed outside, in the world, like

the case of birds nests as objects encoded into their genome, their expression varying from

species to species.

If cognitive tasks escape the above brains and sprawl into bodies—and in some cases into

the environment—what about us? Could it be conceivable that our ways of thinking and ways

of seeing extend beyond our corporeal limits to incorporate nonbiological components? Cave

drawings, hard drives, tapestries, buildings, coffee tables, paintings, the constructed world, the

natural world, the whole world. Where does the mind end and the world begin? No less than

a sea change perspective is required to even begin to see the invisible threads that sew this

neural tapestry together.

Contact details

ARTISTS

ARTISTS