Andrés Pereira Paz: Talismania

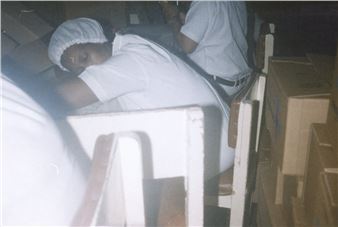

Andrés Pereira Paz seeks a form of creation that allows him to unfold the tangible and concrete dimensions of his own experience: the body of the flesh, the extended body that are our clothes and textiles, and the architectonic body that we adorn with our talismans and manias. The body appears in his pieces as its own clock, dictating the hours in which work may happen, as the muscle cramps and aches, the heavy eyes that beckon us to stop, to rest. His practice extends from drawing, from the changing landscapes around him and from a dream praxis. It is also related to a longer time, the one of the cycles that sway us: Pereira Paz is thinking of draught, the absence of rain that accompanied us in the city until well into the summer, which suddenly transformed into grandiose downpours that marked the evening, the day coming to its end to let the nightly curtain drop. He thinks of the feeling of being at the mercy of the elements, dependent on the resources that unmanageable forces decide to share with us: more time, more water, more fire, more wind.

A talisman, ever since ancient Greece and the first philosophers of Islam, is an object equal parts earthly and divine, concentrating in its materiality the ability to subvert the natural world through the manipulation of the supernatural one. The talisman protects and brings blessings to its holder, most commonly the safe return of a loved one, the safekeeping of valuables, the solution to fertility difficulties and, always, the opportune arrival of rain for a good harvest. It is this last aspect that most interests Pereira Paz. As he sees it, water scarcity is the ultimate clock: the crisis that most evidently marks the beat of our lives, of what they will look like, where they will take place, who will endure—what we will sacrifice and what will perish on the way there.

The pieces in the room are then talismans looking to secure water for its holder and owner; like ancient talismans, they know to blend in with the architecture, to be part of its plea for the protection of those who inhabit it. Pereira Paz’s textiles, like the religious images that result from the Catholic compulsion for representation, also portray, in an emotional key, the torture and desperation of plants and animals in a specific moment in time: the gargantuan fires in the Amazon that have engulfed over 10 million hectares of rainforest in the past few years, most of them intentionally, wreaking misery to install the single-crop farming of soy and African oil palm. The fires have destroyed exorbitant extensions of land in Bolivia, Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, Perú and Venezuela, and with them, the habitats and forms-of-life of countless non-human communities. In his text, In the Forest Ruins, Paulo Tavares follows a series of archaeological and anthropological discoveries that destabilize our established notions of ruin and forest. In European epistemology, the forest is always what lies outside the polis, beyond the human organization of reality, terra nullius available for expropriation and exploitation, the Amazon forest as the perfect exemplification. Today, however, we know that it is the indigenous communities who have inhabited that vast and fertile territory for centuries, that have worked to transform and maintain it in radical ways: the Amazon is a garden, sustained by the knowledge of its peoples; and its ruins, the traces left by those that came before, are evident precisely in its different sediments, its trees, palms and seeds. Tavares mentions Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro who warn us that what the Western imagination constructs as the ‘environment’, the peoples of Amazonia consider “a society of societies, an international arena, a cosmopoliteia”, in which jaguars, monkeys, tatous, capybaras, anteaters, condors, seriemas and toucans, are all citizens and representatives of their own communities, which themselves overlap and are integral to the survival and equilibrium of all the other communities around them, including humans. It is unthinkable that centuries of know-how and care, responsible for the multiplication and conservation of immense biodiversity, are all in grave danger as a result of the boundless greed of a lifestyle that has led to the destruction of 95% of wild fauna in Latin America in less than half a century. It has led to agonizing draughts and endless fires, ever-larger hurricanes and wilder storms, not to mention blood-thirsty geopolitical conflicts. It is a lifestyle that has burnt life down to its core, it has burnt through its center and now only allows us to exist in its extremes, life in the antipodes.

Recommended for you

Andrés Pereira Paz seeks a form of creation that allows him to unfold the tangible and concrete dimensions of his own experience: the body of the flesh, the extended body that are our clothes and textiles, and the architectonic body that we adorn with our talismans and manias. The body appears in his pieces as its own clock, dictating the hours in which work may happen, as the muscle cramps and aches, the heavy eyes that beckon us to stop, to rest. His practice extends from drawing, from the changing landscapes around him and from a dream praxis. It is also related to a longer time, the one of the cycles that sway us: Pereira Paz is thinking of draught, the absence of rain that accompanied us in the city until well into the summer, which suddenly transformed into grandiose downpours that marked the evening, the day coming to its end to let the nightly curtain drop. He thinks of the feeling of being at the mercy of the elements, dependent on the resources that unmanageable forces decide to share with us: more time, more water, more fire, more wind.

A talisman, ever since ancient Greece and the first philosophers of Islam, is an object equal parts earthly and divine, concentrating in its materiality the ability to subvert the natural world through the manipulation of the supernatural one. The talisman protects and brings blessings to its holder, most commonly the safe return of a loved one, the safekeeping of valuables, the solution to fertility difficulties and, always, the opportune arrival of rain for a good harvest. It is this last aspect that most interests Pereira Paz. As he sees it, water scarcity is the ultimate clock: the crisis that most evidently marks the beat of our lives, of what they will look like, where they will take place, who will endure—what we will sacrifice and what will perish on the way there.

The pieces in the room are then talismans looking to secure water for its holder and owner; like ancient talismans, they know to blend in with the architecture, to be part of its plea for the protection of those who inhabit it. Pereira Paz’s textiles, like the religious images that result from the Catholic compulsion for representation, also portray, in an emotional key, the torture and desperation of plants and animals in a specific moment in time: the gargantuan fires in the Amazon that have engulfed over 10 million hectares of rainforest in the past few years, most of them intentionally, wreaking misery to install the single-crop farming of soy and African oil palm. The fires have destroyed exorbitant extensions of land in Bolivia, Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, Perú and Venezuela, and with them, the habitats and forms-of-life of countless non-human communities. In his text, In the Forest Ruins, Paulo Tavares follows a series of archaeological and anthropological discoveries that destabilize our established notions of ruin and forest. In European epistemology, the forest is always what lies outside the polis, beyond the human organization of reality, terra nullius available for expropriation and exploitation, the Amazon forest as the perfect exemplification. Today, however, we know that it is the indigenous communities who have inhabited that vast and fertile territory for centuries, that have worked to transform and maintain it in radical ways: the Amazon is a garden, sustained by the knowledge of its peoples; and its ruins, the traces left by those that came before, are evident precisely in its different sediments, its trees, palms and seeds. Tavares mentions Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro who warn us that what the Western imagination constructs as the ‘environment’, the peoples of Amazonia consider “a society of societies, an international arena, a cosmopoliteia”, in which jaguars, monkeys, tatous, capybaras, anteaters, condors, seriemas and toucans, are all citizens and representatives of their own communities, which themselves overlap and are integral to the survival and equilibrium of all the other communities around them, including humans. It is unthinkable that centuries of know-how and care, responsible for the multiplication and conservation of immense biodiversity, are all in grave danger as a result of the boundless greed of a lifestyle that has led to the destruction of 95% of wild fauna in Latin America in less than half a century. It has led to agonizing draughts and endless fires, ever-larger hurricanes and wilder storms, not to mention blood-thirsty geopolitical conflicts. It is a lifestyle that has burnt life down to its core, it has burnt through its center and now only allows us to exist in its extremes, life in the antipodes.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS