Armin Boehm

In Brain Manipulation Conference we find ourselves in front of a sort of summit of the Earth’s most powerful men. At first sight it looks like they are having a perfectly normal dinner together. But on the table, instead of plates, there are holes through which one looks directly at human brains. A minaret, a warplane, and a Jewish star stand out in the background: elements that clearly refer to the conflict in the Middle East. The figure under the table has to all appearance a human aspect, but on the inside, instead of organs, it is made up of mechanical parts. Nearby, two animals are being cut in half by a saw.

The grotesquely distorted two-side faces allude, even without too much accuracy in the portraits, to Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad.

The structure of Boehm’s painting is stylistically oriented towards the Expressionism of the 1920s, combined with fabric collages typical of Arte Povera. There are also quite unmistaken and intentional references to The Pillars of Society, a painting where George Grosz depicted, with a satirical criticism, the Weimar Republic.

Grosz’ vision hid the first signs of the impending political and military disaster. In much the same way, Boehm’s work alludes to the threatening political conflicts of our time.

Nevertheless, Boehm is not a political painter in the strictest sense. Instead, his dreamlike and surreal compositions are the result of visions and fears that are not only common but also personal. Indeed Boehm will sometimes re-elaborate his dreams in a painting. In his artist approach, the human body, usually depicted in its vulnerability, plays a central role. In Brain Manipulation Conference one sees powerful men represented while they are physically manipulating brains, a glaring metaphor for media bias, for the spread of ‚Äėfake news‚Äô and for the consequent, collective ‚Äėbrainwashing‚Äô.

Armin Boehm's art can be seen as part of the modernist tradition, with its skeptical criticism towards positivist and technological utopias. One of the central motifs of this dark modernism is the tormented body, dismembered and destroyed, the ‚Äėbody in pieces‚Äô, which the art historian Linda Nochlin has analyzed as a ‚Äėmetaphor of modernity‚Äô. It is a modernism that eschews the traditional route of abstraction and, instead of repressing the literary and narrative aspects, intentionally showcases them.

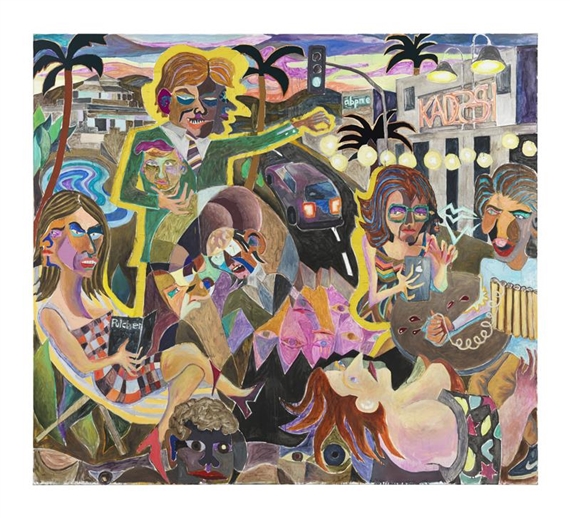

A "different" modernity is also that of gay-lesbian communities, which Armin Boehm celebrates in his Queer Orgy. Among the bystanders, one can recognize the faces of Leigh Bowery, Freddie Mercury, Klaus Nomi, Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith while the DJ behind the mixer is Michel Foucault. But behind the euphoria of the party lurk illness and death, for many of the celebrities in this painting died of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

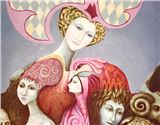

In the healing paintings, often autobiographical, the pessimistic mood is replaced by a new positive and naive attitude. The pastel, soft colors and the playful ornamentation are supposed to engage with Joseph Beuys‚Äô theory of ‚Äč‚Äč‚Äėhealing through art‚Äô. The same human body, often double-faced, that was so terribly afflicted or deformed in previous Boehm‚Äôs works, here seems to have even magical powers.

The double-face motif is not only recurring, but is also the central metaphor of the works on display in the exhibition. Thus while on one hand the surface of the images is often brittle and rough, emphasizing the physical and tangible quality as well as the materiality of the color itself, on the other, the choice of using intense and varied shades functions as a sharp break with the darker palette that characterizes Armin Boehm’s previous works.

Recommended for you

In Brain Manipulation Conference we find ourselves in front of a sort of summit of the Earth’s most powerful men. At first sight it looks like they are having a perfectly normal dinner together. But on the table, instead of plates, there are holes through which one looks directly at human brains. A minaret, a warplane, and a Jewish star stand out in the background: elements that clearly refer to the conflict in the Middle East. The figure under the table has to all appearance a human aspect, but on the inside, instead of organs, it is made up of mechanical parts. Nearby, two animals are being cut in half by a saw.

The grotesquely distorted two-side faces allude, even without too much accuracy in the portraits, to Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad.

The structure of Boehm’s painting is stylistically oriented towards the Expressionism of the 1920s, combined with fabric collages typical of Arte Povera. There are also quite unmistaken and intentional references to The Pillars of Society, a painting where George Grosz depicted, with a satirical criticism, the Weimar Republic.

Grosz’ vision hid the first signs of the impending political and military disaster. In much the same way, Boehm’s work alludes to the threatening political conflicts of our time.

Nevertheless, Boehm is not a political painter in the strictest sense. Instead, his dreamlike and surreal compositions are the result of visions and fears that are not only common but also personal. Indeed Boehm will sometimes re-elaborate his dreams in a painting. In his artist approach, the human body, usually depicted in its vulnerability, plays a central role. In Brain Manipulation Conference one sees powerful men represented while they are physically manipulating brains, a glaring metaphor for media bias, for the spread of ‚Äėfake news‚Äô and for the consequent, collective ‚Äėbrainwashing‚Äô.

Armin Boehm's art can be seen as part of the modernist tradition, with its skeptical criticism towards positivist and technological utopias. One of the central motifs of this dark modernism is the tormented body, dismembered and destroyed, the ‚Äėbody in pieces‚Äô, which the art historian Linda Nochlin has analyzed as a ‚Äėmetaphor of modernity‚Äô. It is a modernism that eschews the traditional route of abstraction and, instead of repressing the literary and narrative aspects, intentionally showcases them.

A "different" modernity is also that of gay-lesbian communities, which Armin Boehm celebrates in his Queer Orgy. Among the bystanders, one can recognize the faces of Leigh Bowery, Freddie Mercury, Klaus Nomi, Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith while the DJ behind the mixer is Michel Foucault. But behind the euphoria of the party lurk illness and death, for many of the celebrities in this painting died of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the healing paintings, often autobiographical, the pessimistic mood is replaced by a new positive and naive attitude. The pastel, soft colors and the playful ornamentation are supposed to engage with Joseph Beuys‚Äô theory of ‚Äč‚Äč‚Äėhealing through art‚Äô. The same human body, often double-faced, that was so terribly afflicted or deformed in previous Boehm‚Äôs works, here seems to have even magical powers.

The double-face motif is not only recurring, but is also the central metaphor of the works on display in the exhibition. Thus while on one hand the surface of the images is often brittle and rough, emphasizing the physical and tangible quality as well as the materiality of the color itself, on the other, the choice of using intense and varied shades functions as a sharp break with the darker palette that characterizes Armin Boehm’s previous works.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS