Bloom Song

Bloom Song (épanouissement) is the change of season, the subtle shift from monochrome to colour, a shaping of poetry from history and a lucid becoming.

Three Black British artists working in different veins, take up poet Robin Coste Lewis‚Äô provocation to ‚Äėstep forth into beauty without political shame.‚Äô

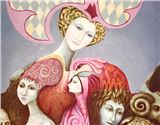

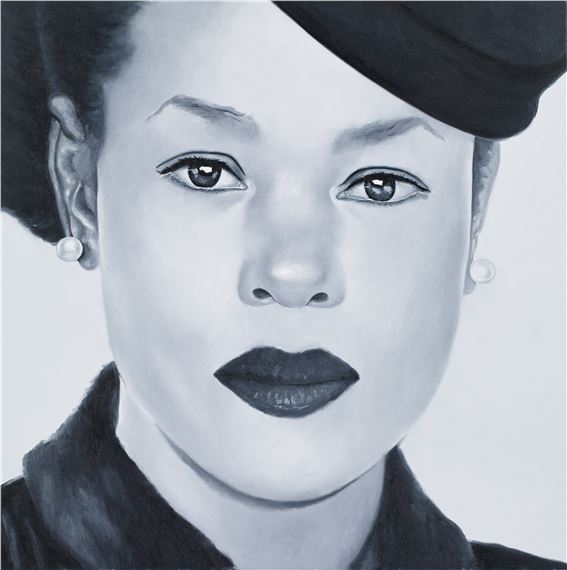

The loveliness of Des Haughton’s trees, branches snowed with bloom, disguise for a moment historical horror within. Speaking directly to these, Eugene Palmer’s portraits, executed in a graduated grisaille, subtly transform and remake the act of looking. While Amanda Holiday’s drawing of ghostly face jugs and towering sunflowers brings the conversation full circle.

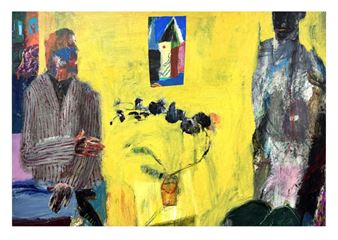

For all three artists, blackness is a given, a perfusion of subject rather than subject itself. Thus, Haughton‚Äôs desire to ‚Äėdepict history through the eyes of trees‚Äô, is both carefree in its intentionality, yet imbued with a history that once saw trees shadowed by lynchings, where branch, beam and wood became material for containment, confinement and geographic dispersal. In fact, Haughton discovered a surprising connection between botanical artists and the slave trade routes ‚Äď since British naturalists of the 1800s travelled on slave ships in order to collect specimens from West Africa and beyond. Haughton says, ‚Äėbotanical drawing is part of the DNA of slave history and some early collectors were slaves.‚Äô Haughton intentionally eschews traditional interpretation of the subject in favour of layered, foliaged and heady beauty.

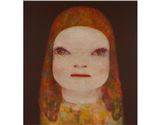

Forms of familial and ancestral memory unite the trio of artists. Over the years, Palmer has documented in paint, his extended and blended family in an array of bold portraits that interrogate and challenge the viewer. The unwavering gaze of Palmer‚Äôs immaculately rendered, mixed-race daughter in this set of four paintings, might at first suggest ‚ÄėInstagram lookism‚Äô and selfie re-mix culture. Yet it is the very act of looking (again) at Palmer‚Äôs work which uncovers ideas about categorisation, race and colourism. Minute colour gradations in the four otherwise identical portraits prompt the viewer to cycle and recycle their own notions of how blackness and beauty are portrayed. Here, Palmer‚Äôs work comes into conversation with that of other black artists notably Gavin Jantjes, an early peer, whose ‚ÄėSouth African Colouring Book‚Äô touches on similar themes. By activating a deeper viewer involvement ‚Äď to look and look again, Palmer‚Äôs work also speaks to that of US artist Amy Sherald who shifts the focus away from skin colour with her own use of grisaille.

Holiday‚Äôs large painted charcoal drawing ‚ÄėFace Jugs and Sunflowers‚Äô emerged from her research into black poetics and in particular, Robin Coste Lewis‚Äô poetic response to an 1882 photograph by J A Palmer titled ‚ÄėWilde Woman of Aiken‚Äô. Holiday became fascinated by the many forms of face jugs, reported to have been created by slaves working around Edgefield in South Carolina and perhaps used as grave markers, since some have been found along the routes of the Underground Railroad. In this drawing, one of a series that depict face jugs, Holiday‚Äôs intention is to convey a sense of a living past and deathly aliveness replete with ancestral memory. In doing so, she speaks to print works by Anselm Kiefer and also Virginia Chihota. In other drawings, Holiday places a figure from the present in communion with the past. The face jugs are containers for a history, that insists on sprouting outwards and upward, taking the form of elongated sunflowers.

Like Palmer, Holiday’s portrayals include members of her own blended and extended family - often conveying a sense of one particular moment in time. Like Haughton too, Holiday’s depiction of uncanny beauty wrestles with the pervasiveness of history’s unsettled and unsettling legacy.

Recommended for you

Bloom Song (épanouissement) is the change of season, the subtle shift from monochrome to colour, a shaping of poetry from history and a lucid becoming.

Three Black British artists working in different veins, take up poet Robin Coste Lewis‚Äô provocation to ‚Äėstep forth into beauty without political shame.‚Äô

The loveliness of Des Haughton’s trees, branches snowed with bloom, disguise for a moment historical horror within. Speaking directly to these, Eugene Palmer’s portraits, executed in a graduated grisaille, subtly transform and remake the act of looking. While Amanda Holiday’s drawing of ghostly face jugs and towering sunflowers brings the conversation full circle.

For all three artists, blackness is a given, a perfusion of subject rather than subject itself. Thus, Haughton‚Äôs desire to ‚Äėdepict history through the eyes of trees‚Äô, is both carefree in its intentionality, yet imbued with a history that once saw trees shadowed by lynchings, where branch, beam and wood became material for containment, confinement and geographic dispersal. In fact, Haughton discovered a surprising connection between botanical artists and the slave trade routes ‚Äď since British naturalists of the 1800s travelled on slave ships in order to collect specimens from West Africa and beyond. Haughton says, ‚Äėbotanical drawing is part of the DNA of slave history and some early collectors were slaves.‚Äô Haughton intentionally eschews traditional interpretation of the subject in favour of layered, foliaged and heady beauty.

Forms of familial and ancestral memory unite the trio of artists. Over the years, Palmer has documented in paint, his extended and blended family in an array of bold portraits that interrogate and challenge the viewer. The unwavering gaze of Palmer‚Äôs immaculately rendered, mixed-race daughter in this set of four paintings, might at first suggest ‚ÄėInstagram lookism‚Äô and selfie re-mix culture. Yet it is the very act of looking (again) at Palmer‚Äôs work which uncovers ideas about categorisation, race and colourism. Minute colour gradations in the four otherwise identical portraits prompt the viewer to cycle and recycle their own notions of how blackness and beauty are portrayed. Here, Palmer‚Äôs work comes into conversation with that of other black artists notably Gavin Jantjes, an early peer, whose ‚ÄėSouth African Colouring Book‚Äô touches on similar themes. By activating a deeper viewer involvement ‚Äď to look and look again, Palmer‚Äôs work also speaks to that of US artist Amy Sherald who shifts the focus away from skin colour with her own use of grisaille.

Holiday‚Äôs large painted charcoal drawing ‚ÄėFace Jugs and Sunflowers‚Äô emerged from her research into black poetics and in particular, Robin Coste Lewis‚Äô poetic response to an 1882 photograph by J A Palmer titled ‚ÄėWilde Woman of Aiken‚Äô. Holiday became fascinated by the many forms of face jugs, reported to have been created by slaves working around Edgefield in South Carolina and perhaps used as grave markers, since some have been found along the routes of the Underground Railroad. In this drawing, one of a series that depict face jugs, Holiday‚Äôs intention is to convey a sense of a living past and deathly aliveness replete with ancestral memory. In doing so, she speaks to print works by Anselm Kiefer and also Virginia Chihota. In other drawings, Holiday places a figure from the present in communion with the past. The face jugs are containers for a history, that insists on sprouting outwards and upward, taking the form of elongated sunflowers.

Like Palmer, Holiday’s portrayals include members of her own blended and extended family - often conveying a sense of one particular moment in time. Like Haughton too, Holiday’s depiction of uncanny beauty wrestles with the pervasiveness of history’s unsettled and unsettling legacy.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS