Residents and Visitors: Twentieth-Century Photographs of Louisiana

With over one hundred examples by dozens of photographers on view, the exhibition offers not only glimpses of Louisiana and its people throughout the twentieth century—primarily in and around New Orleans—but also hints at the depth and breadth of each museum's photography collection. Yet, with an incalculable number of photographs as part of Louisiana's twentieth-century visual history, no exhibition of a hundred pictures can present itself as comprehensive. What can be put forth is a credible and honest attempt to represent many fine image makers falling within those dates, with the knowledge that some important images and photographers will still be left out.

Curators' biases (particular to this exhibition and in general, as the canon of photographic history is rethought) are also considerations in viewing Residents and Visitors. Other variables in the mix are selections based on quality and condition, and whether to present typical or unusual works by a photographer.

The premise for the exhibition, photographs made by those who live or lived in Louisiana for their professional lives and those made by men and women just passing through, might seem to portend pictures splitting along certain lines. One might wonder how those who spend relative moments of time in a place hope to make pictures as thoughtful as those photographers steeped for decades in the culture, the architecture, the humidity of Louisiana. A short answer might be that the visitors' pictures are meaningful and thoughtful in ways that suit photographers rather than an art-viewing public, or the specifics of geography. The inability to offer a neatly packaged answer is part of the question's mystery and attraction, and central to this exhibition.

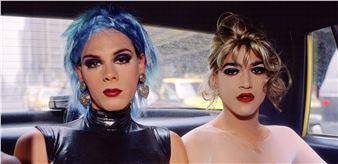

At least part of an answer may be found in how different photographers operate. In the cases of artists as different as Edward Weston and Diane Arbus (visitors), a view of the world and how to shape it through photographs gets packed along with camera equipment and a change of clothes. Upon arriving in a new place, the view is put to use on subject matter encountered by chance or purposeful search. And so Edward Weston's Belle Grove—he was taken there by locals—is as heartfelt, genuine, formally rigorous, and tonally brilliant as his western landscapes, a subject with which he had much greater personal contact and familiarity. Arbus, too, has impressed her preference for certain forms of photography (for example, the environmental portrait, often created in a non-public location) on any locale where she finds herself. It is a portable aesthetic, incorporating subjects not bound to a specific locale.

For pictures that do demand subjects specific to a place, the resident may indeed have an "edge" over the visitor, which can lead to a consideration of the chicken-and-egg variety: what comes first, the vision or the subject? Attempting to formulate an answer that fits all situations might be a fool's errand, if not a logical fallacy. Michael P. Smith's self-assigned interest in the broad musical culture of New Orleans drew him into places that visitors could scarcely know of, much less frequent. Smith's view was a long one, developed over decades where patience and research were as important as camera and film.

A. J. Meek, of Baton Rouge, has also sustained a vision of south Louisiana landscapes, people, and buildings over many years. Being comfortable in a place and having faith in the ability of a location to not only sustain, but to constantly challenge and reinvigorate an artistic outlook and sensibility, is part of the resident photographer's equipment and outlook. This is not to say that resident photographers have no world view when compared to visitors, but that the view has been shaped by different factors. Perhaps the most obvious case-in-point for that is Clarence Laughlin, who as a resident of Louisiana chose to perceive his native surroundings with the wonder of a visitor. But Laughlin's interest, explained by his writing, is the world of symbols as stand-ins for things—emotions, fantasies, nightmares—not photographable.

A third category of photographers may be considered: those having traits of both the resident and the visitor. Lee Friedlander's multiple visits to Louisiana over half a century, and his dedication to certain elements of the city's musical culture may inch him toward a hybrid photographer: the habitual visitor. Others in this exhibition fitting that general profile include Ralston Crawford, Michael A. Smith, and Allen Hess.

Perhaps more than any other visual medium, photographs have been welcomed into museum collections not only on the basis of who created them, but for the power and uniqueness of their imagery. Ernest J. Bellocq's enigmatic portraits of women in Storyville were produced by a commercial photographer whose paid work appeared sufficient to the needs of his clients, but was not artistically innovative or groundbreaking. Judged on that main body of his work, Bellocq may have never made it into the collection of an art museum, though his forthright presentation of subjects is entirely appropriate and useful in the collections of a history museum.

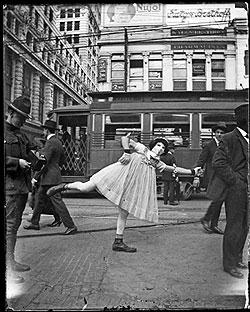

Artistic intent may not have been at the forefront of Charles Franck's dynamic photograph of the chutes and bins (Annex Bin Floor) of New Orleans's public grain elevator, or John T. Mendes's stylish and whimsical Carnival Masker, figuratively balancing on one foot between the worlds of fantasy and reality, but each image certainly holds its own as a fresh visual statement of its time, the late 1910s.

Like these two, many journeymen commercial photographers and dedicated amateurs—both residents and visitors—produce images of stunning originality, but their road to recognition beyond a small sphere of clients and admirers depends on many factors: technical skills, insightful vision, compelling subjects, hard work and, the great equalizer, luck. It is the latter trait, unquantifiable and subject to no external influences, that may well be the critical factor in unearthing photographers of excellence and insight yet unknown.

Recommended for you

With over one hundred examples by dozens of photographers on view, the exhibition offers not only glimpses of Louisiana and its people throughout the twentieth century—primarily in and around New Orleans—but also hints at the depth and breadth of each museum's photography collection. Yet, with an incalculable number of photographs as part of Louisiana's twentieth-century visual history, no exhibition of a hundred pictures can present itself as comprehensive. What can be put forth is a credible and honest attempt to represent many fine image makers falling within those dates, with the knowledge that some important images and photographers will still be left out.

Curators' biases (particular to this exhibition and in general, as the canon of photographic history is rethought) are also considerations in viewing Residents and Visitors. Other variables in the mix are selections based on quality and condition, and whether to present typical or unusual works by a photographer.

The premise for the exhibition, photographs made by those who live or lived in Louisiana for their professional lives and those made by men and women just passing through, might seem to portend pictures splitting along certain lines. One might wonder how those who spend relative moments of time in a place hope to make pictures as thoughtful as those photographers steeped for decades in the culture, the architecture, the humidity of Louisiana. A short answer might be that the visitors' pictures are meaningful and thoughtful in ways that suit photographers rather than an art-viewing public, or the specifics of geography. The inability to offer a neatly packaged answer is part of the question's mystery and attraction, and central to this exhibition.

At least part of an answer may be found in how different photographers operate. In the cases of artists as different as Edward Weston and Diane Arbus (visitors), a view of the world and how to shape it through photographs gets packed along with camera equipment and a change of clothes. Upon arriving in a new place, the view is put to use on subject matter encountered by chance or purposeful search. And so Edward Weston's Belle Grove—he was taken there by locals—is as heartfelt, genuine, formally rigorous, and tonally brilliant as his western landscapes, a subject with which he had much greater personal contact and familiarity. Arbus, too, has impressed her preference for certain forms of photography (for example, the environmental portrait, often created in a non-public location) on any locale where she finds herself. It is a portable aesthetic, incorporating subjects not bound to a specific locale.

For pictures that do demand subjects specific to a place, the resident may indeed have an "edge" over the visitor, which can lead to a consideration of the chicken-and-egg variety: what comes first, the vision or the subject? Attempting to formulate an answer that fits all situations might be a fool's errand, if not a logical fallacy. Michael P. Smith's self-assigned interest in the broad musical culture of New Orleans drew him into places that visitors could scarcely know of, much less frequent. Smith's view was a long one, developed over decades where patience and research were as important as camera and film.

A. J. Meek, of Baton Rouge, has also sustained a vision of south Louisiana landscapes, people, and buildings over many years. Being comfortable in a place and having faith in the ability of a location to not only sustain, but to constantly challenge and reinvigorate an artistic outlook and sensibility, is part of the resident photographer's equipment and outlook. This is not to say that resident photographers have no world view when compared to visitors, but that the view has been shaped by different factors. Perhaps the most obvious case-in-point for that is Clarence Laughlin, who as a resident of Louisiana chose to perceive his native surroundings with the wonder of a visitor. But Laughlin's interest, explained by his writing, is the world of symbols as stand-ins for things—emotions, fantasies, nightmares—not photographable.

A third category of photographers may be considered: those having traits of both the resident and the visitor. Lee Friedlander's multiple visits to Louisiana over half a century, and his dedication to certain elements of the city's musical culture may inch him toward a hybrid photographer: the habitual visitor. Others in this exhibition fitting that general profile include Ralston Crawford, Michael A. Smith, and Allen Hess.

Perhaps more than any other visual medium, photographs have been welcomed into museum collections not only on the basis of who created them, but for the power and uniqueness of their imagery. Ernest J. Bellocq's enigmatic portraits of women in Storyville were produced by a commercial photographer whose paid work appeared sufficient to the needs of his clients, but was not artistically innovative or groundbreaking. Judged on that main body of his work, Bellocq may have never made it into the collection of an art museum, though his forthright presentation of subjects is entirely appropriate and useful in the collections of a history museum.

Artistic intent may not have been at the forefront of Charles Franck's dynamic photograph of the chutes and bins (Annex Bin Floor) of New Orleans's public grain elevator, or John T. Mendes's stylish and whimsical Carnival Masker, figuratively balancing on one foot between the worlds of fantasy and reality, but each image certainly holds its own as a fresh visual statement of its time, the late 1910s.

Like these two, many journeymen commercial photographers and dedicated amateurs—both residents and visitors—produce images of stunning originality, but their road to recognition beyond a small sphere of clients and admirers depends on many factors: technical skills, insightful vision, compelling subjects, hard work and, the great equalizer, luck. It is the latter trait, unquantifiable and subject to no external influences, that may well be the critical factor in unearthing photographers of excellence and insight yet unknown.

Artists on show

Contact details

ARTISTS

ARTISTS