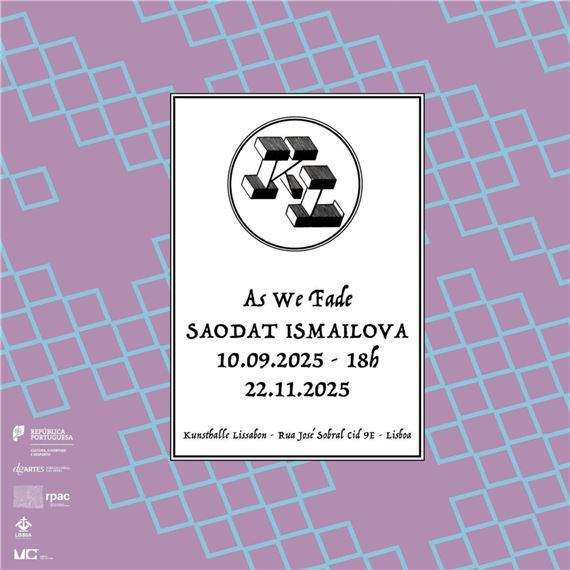

Saodat Ismailova: As We Fade

Kunsthalle Lissabon is pleased to present "As We Fade," a solo exhibition by the renowned Uzbek filmmaker and multimedia artist Saodat Ismailova. Running from September 10 to November 22, 2025, this unique exhibition unfolds as a two-channel film installation. Visitors are invited to engage directly with the complex history of Sulaiman-Too Mountain's sacred rituals, political imposition, and cultural transformation. This narrative is both captivating and thought-provoking as it brings about questions on how state power, historical ruptures, and the passing of time alter sacred sites, raising questions about what is remembered or erased, and what resists oblivion.

In the film As We Fade, Ismailova traces the layered story of Sulaiman-Too Mountain, Central Asia’s oldest pilgrimage site, named after the Arabic legend that the prophet Sulaiman rested there. Rising from the Fergana region in the city of Osh, Kyrgyzstan, the mountain has served as a focal point for spiritual life across centuries. Archeological evidence reveals that the mountain has been venerated for over a millennium, with traces of pre-Islamic worship still visible in petroglyphs and cave sanctuaries. In the Islamic period, mosques and pilgrimage routes were established, resulting in Osh being an important point along the Silk Road. During the Soviet era, efforts by the authorities to ban religious practices in Sulaiman-Too altered its sacred character. Converting the most revered cave, Rushon Onqur, into a modernist restaurant, along with a panoramic viewing deck at the summit. Afterwards, it was repurposed as a national historical and archeological museum. Despite these interventions, the mountain retained its spiritual significance, continuing to attract pilgrims and researchers alike, those drawn to the healing rituals, oral traditions, and cosmological beliefs embedded in its stone.

Without voice-over or didactic captions, Ismailova seamlessly weaves archival footage of rituals performed on the different parts of the mountain, dating back to as early as 1929, featuring construction and Soviet-era scenes alongside contemporary observational shots of the museum interior and the surrounding landscape. The 19-minute film is projected onto twenty-four suspended silk panels, which are made in Margilan, one for each frame per second, so that images and landscape observations shift and fade as viewers walk through the space. How does memory fade? Language? Stories and traumas? Here, the exhibition addresses the material representation of visual storytelling through light projection on the surface of the ancient craft of silk weaving from the Fergana valley, a valley that experienced the most complicated transformation during the years of Soviet politics in the region. Ambient sound, wind through the stone, and distant voices underscore the tension between what was intended and what endured, echoing local opinion that the transformation of a sacred site into a place of leisure could not be sustained; an act of desacralization too deep to remain unresolved.

Alongside the film, the exhibition features "The Mountain Our Bodies Emptied," a reduced-scale resin cast based on LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scans, a technology that uses laser light to create precise three-dimensional models of surfaces, of Tamchi Tomar Cave, the most active and venerated cave in the mountain. For centuries, on this site, visitors sought healing by inserting or pressing body parts into its natural hollows, believing that the depressions of the mountain could absorb pain or cure afflictions. These gestures, repeated over generations, have shaped the surface of the stone and the understanding of the place as a middle point between material and spiritual worlds. The sculpture’s translucent surface captures both the cave’s geological form and its ritual resonance. Together with the film, the sculpture extends Ismailova’s reflection on the significance ingrained in sacred sites, where physical and spiritual presence, collective memories, and cultural impositions leave their marks even as their meanings are contested.

Presented in Lisbon, a city shaped by its cycles of empire, trade, and urban renewal, As We Fade speaks to how places of worship, reunion, community, and heritage are adapted, overwritten, taken, or reclaimed over time. In this context, Ismailova’s work prompts us to consider: when a site’s original meaning is obscured, what evidence remains of its spiritual past, and how might active witnessing help recover traces of collective memory? What stays and what fades?

Kunsthalle Lissabon is pleased to present "As We Fade," a solo exhibition by the renowned Uzbek filmmaker and multimedia artist Saodat Ismailova. Running from September 10 to November 22, 2025, this unique exhibition unfolds as a two-channel film installation. Visitors are invited to engage directly with the complex history of Sulaiman-Too Mountain's sacred rituals, political imposition, and cultural transformation. This narrative is both captivating and thought-provoking as it brings about questions on how state power, historical ruptures, and the passing of time alter sacred sites, raising questions about what is remembered or erased, and what resists oblivion.

In the film As We Fade, Ismailova traces the layered story of Sulaiman-Too Mountain, Central Asia’s oldest pilgrimage site, named after the Arabic legend that the prophet Sulaiman rested there. Rising from the Fergana region in the city of Osh, Kyrgyzstan, the mountain has served as a focal point for spiritual life across centuries. Archeological evidence reveals that the mountain has been venerated for over a millennium, with traces of pre-Islamic worship still visible in petroglyphs and cave sanctuaries. In the Islamic period, mosques and pilgrimage routes were established, resulting in Osh being an important point along the Silk Road. During the Soviet era, efforts by the authorities to ban religious practices in Sulaiman-Too altered its sacred character. Converting the most revered cave, Rushon Onqur, into a modernist restaurant, along with a panoramic viewing deck at the summit. Afterwards, it was repurposed as a national historical and archeological museum. Despite these interventions, the mountain retained its spiritual significance, continuing to attract pilgrims and researchers alike, those drawn to the healing rituals, oral traditions, and cosmological beliefs embedded in its stone.

Without voice-over or didactic captions, Ismailova seamlessly weaves archival footage of rituals performed on the different parts of the mountain, dating back to as early as 1929, featuring construction and Soviet-era scenes alongside contemporary observational shots of the museum interior and the surrounding landscape. The 19-minute film is projected onto twenty-four suspended silk panels, which are made in Margilan, one for each frame per second, so that images and landscape observations shift and fade as viewers walk through the space. How does memory fade? Language? Stories and traumas? Here, the exhibition addresses the material representation of visual storytelling through light projection on the surface of the ancient craft of silk weaving from the Fergana valley, a valley that experienced the most complicated transformation during the years of Soviet politics in the region. Ambient sound, wind through the stone, and distant voices underscore the tension between what was intended and what endured, echoing local opinion that the transformation of a sacred site into a place of leisure could not be sustained; an act of desacralization too deep to remain unresolved.

Alongside the film, the exhibition features "The Mountain Our Bodies Emptied," a reduced-scale resin cast based on LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scans, a technology that uses laser light to create precise three-dimensional models of surfaces, of Tamchi Tomar Cave, the most active and venerated cave in the mountain. For centuries, on this site, visitors sought healing by inserting or pressing body parts into its natural hollows, believing that the depressions of the mountain could absorb pain or cure afflictions. These gestures, repeated over generations, have shaped the surface of the stone and the understanding of the place as a middle point between material and spiritual worlds. The sculpture’s translucent surface captures both the cave’s geological form and its ritual resonance. Together with the film, the sculpture extends Ismailova’s reflection on the significance ingrained in sacred sites, where physical and spiritual presence, collective memories, and cultural impositions leave their marks even as their meanings are contested.

Presented in Lisbon, a city shaped by its cycles of empire, trade, and urban renewal, As We Fade speaks to how places of worship, reunion, community, and heritage are adapted, overwritten, taken, or reclaimed over time. In this context, Ismailova’s work prompts us to consider: when a site’s original meaning is obscured, what evidence remains of its spiritual past, and how might active witnessing help recover traces of collective memory? What stays and what fades?

Artists on show

Contact details

ARTISTS

ARTISTS