Kenro Izu - Bhutan: Sacred Within

Kenro Izu, who grew up in Japan but has lived in New York since the early 1970s, is widely known both for his accomplishments as a photographer and for the organisation he established, Friends Without a Border, which provides health care for the children of Cambodia and supports the Angkor Children’s Hospital. Friends Without a Border grew out of Izu’s concern for the children he encountered while photographing the Angkor temples...

Heather Snider / Eyemazing

01 Dec, 2008

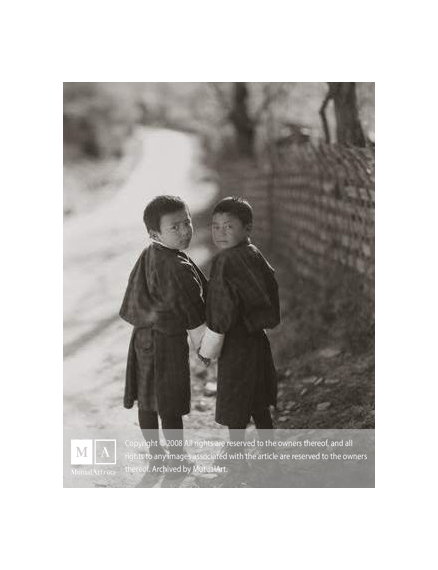

Kenro Izu, who grew up in Japan but has lived in New York since the early 1970s, is widely known both for his accomplishments as a photographer and for the organisation he established, Friends Without a Border, which provides health care for the children of Cambodia and supports the Angkor Children’s Hospital. Friends Without a Border grew out of Izu’s concern for the children he encountered while photographing the Angkor temples. It was his compassion for the people who live in and among such sacred places that also attracted Izu to Bhutan, where citizens enjoy a uniquely sheltered, simple quality of life. From 2002 to 2007 Izu made five trips to Bhutan to photograph what eventually became an entire book of images, Bhutan: sacred within (Nazraeli Press, 2007). More than in any of his previous series, Izu photographed the people whose rituals, traditions, and lifestyle embody the spirituality of their sacred sites.

Izu’s approach to photography is purely documentary and he has stated that he is more interested in capturing what he sees than creating an image. This literal approach to the medium is echoed in his choice of materials: his platinum palladium contact prints possess an uncanny clarity. He brings the viewer into a shared intimacy with the Bhutanese people and their environment, providing a moment of repose just long enough to take in a breath of peaceful otherness and to contemplate a different kind of existence.

His project in Bhutan now completed, Kenro Izu shared some of his experience in the country and of the people living within its fold.

Heather Snider: What were the circumstances of your first trip to Bhutan? Did you know you wanted to photograph there before you went?

Kenro Izu: For a long time I had been interested in Bhutan’s measurement of national success known as “Gross National Happiness.” When I was travelling in Tibet from 1999 to 2002, fellow travellers told me about the well-preserved sacred places in Bhutan and the simple and pure life of the Bhutanese who practice a form of Tibetan Buddhism. As my friends described it, “the whole country is sacred.”

During my first two trips to Bhutan I travelled through the country in search of sacred places and monuments. I was prepared and fully equipped to photograph any subject that resonated with my heart. I trekked through the mountains to remote monasteries and drove to eastern cities to photograph those places considered sacred. I was impressed with the people whom I encountered and travelled with, by their selflessness and their strong beliefs. I was inspired to visit again and again.

HS: You have also travelled and photographed in neighbouring Tibet. How would you compare Tibet and Bhutan?

KI: In Tibet most of the man-made sacred places were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and some that you do see are actually reconstructed, whereas in Bhutan they are well preserved, having been taken care of by the people with pride over the centuries. In Tibet, over the three years that I visited, I could see that the people’s attitude towards material things had grown quite a bit. My Tibetan assistants were discussing plans to open a gelato shop in Lhasa; these are the same people who were previously meditating and discussing a free Tibet. In contrast, the people I know in Bhutan are now discussing democracy, which has just begun in the country, and questioning how they can maintain “Gross National Happiness.” They too are talking of opening restaurants or tour service businesses. The big difference between the two countries is that one is under the governance of China while the other is independent and free. The difference in the quality of “happiness” seems apparent there.

HS: Your book opens with a portrait of Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the King of Bhutan who, along with his father, has become widely known for his benevolent policies. How did you have the opportunity to photograph him? How would you describe him? KI: To be clear, “Gross National Happiness” was the pronouncement made in 1980 by his father, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. Jigme Khesar was Crown Prince in November of 2007, when I got permission, and when I returned to photograph him in February of 2008 he had been crowned King. An artist-scholar I met in Bhutan who liked my photographs introduced me to him. The King is young, charming, very social, and best of all, a good amateur photographer. He appreciated my photographs in the books I sent prior to my visit. He was enthusiastic about film photography, which he thinks possesses something that can’t be found in digital photography. Obviously I was impressed by his insight. After our photo-shoot he invited me to his palace for tea another day and wanted to talk more about photography. He showed me some of his own photographs and asked my opinion about them and about equipment, technique, etcetera. We had a casual and nice time together.

HS: In Bhutan you photographed people more than you have done in your previous series. What were the reasons for this shift?

KI: During my second trip, I started to feel that an important element of the sacred places was missing. Meeting many Bhutanese people, high Lamas, novice monks, farmers, children, caretakers of temples, nuns, and even officials, I realised they were the ones sustaining, and handing down through generations, the sacred places of this country. I realised that without including the people, my photographs of the sacred places would not be complete. Without the people who pray, practice, maintain, and believe, the places I photographed were merely shells of true spirit.

HS: How did you form the connections with people that allowed you to photograph them?

KI: Some were by introduction of friends I have there and some I just met at various locations and asked for permission. Others I learned of by their reputation of importance in the culture and religion. I would explain my project to them in order to obtain permission. I brought one of my books as a sample of my work. Later I brought sample photographs of Bhutanese portraits I had made.

HS: Buddhism is a fundamental part of everyday life in Bhutan. How much did you learn or know about the Tsechu festivals and other Buddhist rituals?

KI: Not much beyond knowledge from a guidebook. Wherever I travel, instead of studying the culture, I try to absorb and accept it as it is. To photograph I need to sense with my heart more than understand with my mind.

HS: What is your religious background? Were your own beliefs affected by your experience in Bhutan?

KI: I am Buddhist in broad terms. I don’t practice but I believe in Buddhism not so much as a religion but as knowledge of living peacefully.

HS: How prevalent is photography in Bhutan? Do many people have their own cameras?

KI: I don’t think they do. Maybe that is one of reasons why the people I photographed were so natural, besides the fact of their lack of self-consciousness about appearance.

HS: How did the Bhutanese people respond to the photographs of the ceremonies and masks? Do you feel that the photographs might have changed their perception of their ceremonies in any way?

KI: I have not had a chance to show my ceremonial photos to the people who posed for me. I showed my book to several people and they all said they had never seen photographs of themselves, including ceremonial ones, in the way I photographed. The director of National Museum in Paro wanted to have an exhibition there to provide an opportunity for the rural people to see sacred sites that the average Bhutanese may not be able to visit, and to show the city people the regional festivals that they may never see. My sample photographs, which I took to Bhutan, attracted many people who wanted to be photographed. I don’t know the real reason, but it may be because of the formal style of my portraiture.

HS: You also photographed the landscape extensively. Is the country truly as undeveloped as it appears in these photographs?

KI: It is more undeveloped than my photographs even show. If you look at a map, you see the country is mostly in the Himalaya Mountains. There is so little flat land that there is only one airport. There is only one road, often a one-lane road, from west to east, connecting the only airport, in Paro, to the capital city, Thimphu, and to the city in the far east of the country. In other directions there were a few dirt roads and mostly paths, only passable by foot and mule. I travelled with 4-wheel drive and did many treks with porters and mules to reach the monasteries, sacred lakes, mountains, etcetera.

HS: Can you discuss your process in the field? You photograph in several large formats, why did you choose the 14 x 20 inch negatives for this project?

KI: For the last 25 years I have almost exclusively used the 14 x 20, with the exception of one trip to Mexico with an 8 x 10 inch camera. I like to have the largest negative possible in order to contact print my platinum palladium prints. I prefer not to enlarge the negative and the 14 x 20 inch size is large enough yet portable enough to carry through the mountains, jungle or desert.

HS: Some of the sites you photographed are always enveloped in clouds. How would you describe the effects of this, on both the landscape and the people who are literally living in the clouds?

KI: They are true scenes that occur every morning there. I try to maintain my position as an observer and document as precisely as possible the scene as I see it. I try not to make the scene overly emotional through photographic technique. I also try not to express any particular message.

HS: Can you tell us your thoughts behind the title for this series, sacred within?

KI: After more than 20 years of travelling to and photographing sacred places, I realised the essence of sacredness lies within the people’s hearts; those who believe, preserve, and pass on the sacred places to the next generation. Without those people, sacred places are no different from any ordinary mountain, lake, or building.

HS: Is your work in Bhutan completed or will you go back? How do you know when a project such as this is finished?

KI: I might return. But I know my work is over in Bhutan unless I find something more to interest me there. I feel I reached the height of my excitement. If I continue, I may just be adding more places and people but not necessarily raising the level of my inspiration. I am excited to move onto the next place to find the “sacred within” people of different culture and thoughts, in search of my own passage. As Buddhism teaches, nothing is permanent and everything is frail.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS