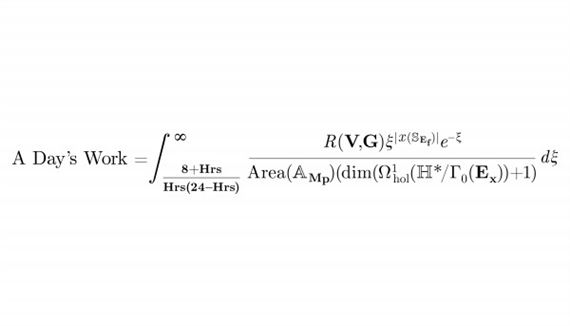

A Day's Work

SKK Soest, The Stiftung Konzeptuelle Kunst is delighted to present A DayŌĆÖs Work selected by British artist Susan Morris. This exhibition brings together a group of 21 international artists who address issues around temporality, subjectivity, labour and art.

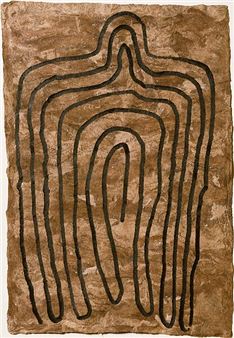

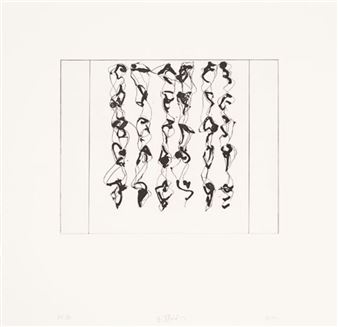

Some of the artists in the exhibition are concerned with the rationalization of time and natural phenomena; others investigate the alienating effects of new technologies on workersŌĆÖ lives while others still engage in a more private, personal struggle with the capricious nature of the materials they have chosen to work with.

Often these overlap, such as in the work of KP Brehmer which, as Margaret Iversen argues in her catalogue essay Diagramming the Day, takes the form of a struggle between the effort to systematically record things, such as the changing colour of the sky over 24 hours, and the unruly nature of the watery paints he uses for the task that leak out of the very system he has created to contain them. Similarly, Mike Meir├®ŌĆÖs crushed newspaper reconfigures the grid-like ŌĆśjournalŌĆÖ as chaotic splotch.

In Renaissance frescos, the giornatae refers to the area an artist could paint in a single day. A measurement of human labour is thus embedded in artwork dating from the 14th and 15th century, its calculation based on how much physical energy a painter may have set against the material properties of the paint itself, such as the time it took to dry.

In everyday usage, the phrase ŌĆśa dayŌĆÖs workŌĆÖ might be an expression of satisfaction, signalling the end of a task. However, it could also be the amount of paid labour you need in order to survive.

Recommended for you

SKK Soest, The Stiftung Konzeptuelle Kunst is delighted to present A DayŌĆÖs Work selected by British artist Susan Morris. This exhibition brings together a group of 21 international artists who address issues around temporality, subjectivity, labour and art.

Some of the artists in the exhibition are concerned with the rationalization of time and natural phenomena; others investigate the alienating effects of new technologies on workersŌĆÖ lives while others still engage in a more private, personal struggle with the capricious nature of the materials they have chosen to work with.

Often these overlap, such as in the work of KP Brehmer which, as Margaret Iversen argues in her catalogue essay Diagramming the Day, takes the form of a struggle between the effort to systematically record things, such as the changing colour of the sky over 24 hours, and the unruly nature of the watery paints he uses for the task that leak out of the very system he has created to contain them. Similarly, Mike Meir├®ŌĆÖs crushed newspaper reconfigures the grid-like ŌĆśjournalŌĆÖ as chaotic splotch.

In Renaissance frescos, the giornatae refers to the area an artist could paint in a single day. A measurement of human labour is thus embedded in artwork dating from the 14th and 15th century, its calculation based on how much physical energy a painter may have set against the material properties of the paint itself, such as the time it took to dry.

In everyday usage, the phrase ŌĆśa dayŌĆÖs workŌĆÖ might be an expression of satisfaction, signalling the end of a task. However, it could also be the amount of paid labour you need in order to survive.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS