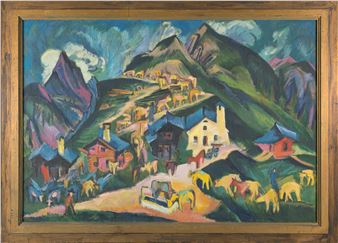

Otto Muellers Landscape

For centuries, Arcadia was a place of yearning, a place of which one dreamed in order to escape the social mores of court life or city life. In play and in poetry, the nobleman imagined himself as a shepherd living in frugal simplicity, in tune with nature, encountering others on an equal footing and able to love unfettered by social constraints. In this life he would be at leisure to produce love poetry, which actually finds expression in real life as pastoral poetry. The pastoral thus eliminates the difference between poetry and truth, play and reality, the unity between people and nature is re-established, and thus also the oneness and harmony of the cosmos. But as this can only ever happen for a short moment, and in play and poetry, an elegiac tone creeps into this poetry, a melancholic mood permeated by an awareness of its transitory nature. In painting, pastoral Arcadia is present in the airy lightness of Watteau’s Fêtes galantes rather than in Poussin’s heavy Classicism.

As long as the aristocratic conditions existed, the pastoral found expression in play and poetry and was repeated in infinite variations. Finally, however, Rousseau introduced some seriousness and called for people to retreat from society in order to be able to realize their own inner nature in the nature around them. Against the background of the pastoral, he demanded natural conditions not only in recreation and in art, but also in real life. In the French Revolution, he was thus seen as a pioneer in the liberation from the reigning social conditions.

In the world of art, first John Constable and then the artists of the Barbizon school left the confines of the studio and went out into nature in order to portray it for its own sake, free of academic requirements, free of narratives from the Bible, myth or history, capturing it just as they experienced it first-hand. Since the surrounding landscape could change at a moment’s notice depending on the weather and light conditions, a certain rapidity was required in transferring the natural world to the canvas. Each artist had to find their own way of achieving this and be aware of how the picture emerged. Nineteenth century landscape painting thus evolved from nature outdoors, via the artist’s own nature, to the nature of painting itself, and in this way represents a major step in the development of the artist and of art towards autonomy and self-determination, free of external constraints.

Otto Mueller prefers the soft, flowing tones of lithography to achieve a lyrical tone in his works, rather than the hard scratching on a metal plate involved in etching, which was Nolde’s preferred technique, or gouging out shapes in hard wood to form a woodcut, Kirchner’s, Heckel’s and Schmidt-Rottluff’s most frequently employed technique.

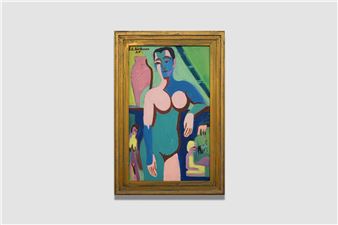

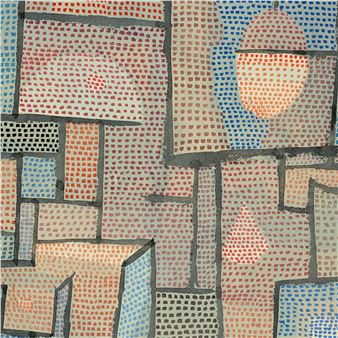

Mueller’s striving for harmony can be seen not only in his subjects and the materials he uses, but also in the structures he chooses. Many of his pictures are based on a triangle, or two triangles joining to form a diamond. These shapes can be found in a crouching figure, the propped-up leg of a recumbent body, a bent arm, an inclined head, or the outline of a chin, chest or head. Constellations of figures form the same triangular shape as dunes, grassy mounds and mountains, or run parallel to branches, which traverse the picture diagonally, like leaves and ferns. Bent bodies seem to be fitted into an imaginary diamond pattern, a grid form that actually appears on the walls in the background of some of his self-portraits.

Recommended for you

For centuries, Arcadia was a place of yearning, a place of which one dreamed in order to escape the social mores of court life or city life. In play and in poetry, the nobleman imagined himself as a shepherd living in frugal simplicity, in tune with nature, encountering others on an equal footing and able to love unfettered by social constraints. In this life he would be at leisure to produce love poetry, which actually finds expression in real life as pastoral poetry. The pastoral thus eliminates the difference between poetry and truth, play and reality, the unity between people and nature is re-established, and thus also the oneness and harmony of the cosmos. But as this can only ever happen for a short moment, and in play and poetry, an elegiac tone creeps into this poetry, a melancholic mood permeated by an awareness of its transitory nature. In painting, pastoral Arcadia is present in the airy lightness of Watteau’s Fêtes galantes rather than in Poussin’s heavy Classicism.

As long as the aristocratic conditions existed, the pastoral found expression in play and poetry and was repeated in infinite variations. Finally, however, Rousseau introduced some seriousness and called for people to retreat from society in order to be able to realize their own inner nature in the nature around them. Against the background of the pastoral, he demanded natural conditions not only in recreation and in art, but also in real life. In the French Revolution, he was thus seen as a pioneer in the liberation from the reigning social conditions.

In the world of art, first John Constable and then the artists of the Barbizon school left the confines of the studio and went out into nature in order to portray it for its own sake, free of academic requirements, free of narratives from the Bible, myth or history, capturing it just as they experienced it first-hand. Since the surrounding landscape could change at a moment’s notice depending on the weather and light conditions, a certain rapidity was required in transferring the natural world to the canvas. Each artist had to find their own way of achieving this and be aware of how the picture emerged. Nineteenth century landscape painting thus evolved from nature outdoors, via the artist’s own nature, to the nature of painting itself, and in this way represents a major step in the development of the artist and of art towards autonomy and self-determination, free of external constraints.

Otto Mueller prefers the soft, flowing tones of lithography to achieve a lyrical tone in his works, rather than the hard scratching on a metal plate involved in etching, which was Nolde’s preferred technique, or gouging out shapes in hard wood to form a woodcut, Kirchner’s, Heckel’s and Schmidt-Rottluff’s most frequently employed technique.

Mueller’s striving for harmony can be seen not only in his subjects and the materials he uses, but also in the structures he chooses. Many of his pictures are based on a triangle, or two triangles joining to form a diamond. These shapes can be found in a crouching figure, the propped-up leg of a recumbent body, a bent arm, an inclined head, or the outline of a chin, chest or head. Constellations of figures form the same triangular shape as dunes, grassy mounds and mountains, or run parallel to branches, which traverse the picture diagonally, like leaves and ferns. Bent bodies seem to be fitted into an imaginary diamond pattern, a grid form that actually appears on the walls in the background of some of his self-portraits.

ARTISTS

ARTISTS