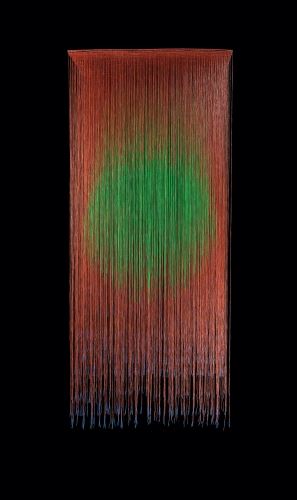

Through The Eye of The Needle

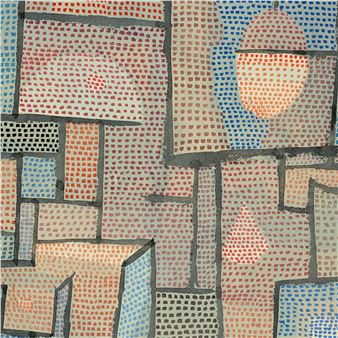

The Poet and Through the Eye of the Needle explore contemporary artists engaged with the texture and materiality of fiber as a primary medium. At present, we are witnessing a moment where the history of modern art is being rewritten and course-corrected to include artists whose chosen media has heretofore left them out of the larger discourse around modern and contemporary practice. In many cases, these artists have been predominately women who in some cases have been accused of engaging in ÔÇ£womenÔÇÖs work,ÔÇØ a derogatory and oftentimes punitive designation meant to relegate their work into an inescapable, gender-biased category. Rather than shying away from these categories, a new generation of art historians and curators have leaned into these histories to better understand the contributions of women artists and their work, which in fact has both elevated and complicated our understanding of modern art and abstraction over the last century.

Our understanding around ideas about abstraction, spirituality and magic, for example, have recently be- gun to shift as we learn of the contributions of artists such as Hilma af Klimt, Agnes Pelton and Emma Kunz. Each in their own way they sought to give light to the mystical sources and inspirations that gave ÔÇ£formÔÇØ to otherwise intangible concepts ÔÇô ideas not found in nature but that live in the imagination. Interests in non-western religions and theosophy led many of these artists to seek knowledge from leading figures such as the Russian e╠ümigre╠ü Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy1 , and Annie Besant, author of the influential book Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation (1901), that sought to visualize thoughts, experiences, emotions and music. Simultaneous to these formal explorations were investigations into materials and craft that were first instigated by the legendary figure Annie Albers who was forced to work in the weaving studio at the Bauhaus because it was the only area open to women. Later she would say, ÔÇ£In my case it was threads that caught me, really against my will. To work with threads seemed sissy to me. I wanted something to be conquered. But circumstances held me to threads and they won me over.ÔÇØ2 Gunta Sto╠êlzl (5 March 1897 ÔÇô 22 April 1983), the head of the Bauhaus weaving workshop where Albers studied, emphasized the singular nature of the woven form, at once a platform for the investigation of form, color, texture and material specific to weaving and an opportunity for the woven object to lay claim to itself as a modernist medium.

Recommended for you

The Poet and Through the Eye of the Needle explore contemporary artists engaged with the texture and materiality of fiber as a primary medium. At present, we are witnessing a moment where the history of modern art is being rewritten and course-corrected to include artists whose chosen media has heretofore left them out of the larger discourse around modern and contemporary practice. In many cases, these artists have been predominately women who in some cases have been accused of engaging in ÔÇ£womenÔÇÖs work,ÔÇØ a derogatory and oftentimes punitive designation meant to relegate their work into an inescapable, gender-biased category. Rather than shying away from these categories, a new generation of art historians and curators have leaned into these histories to better understand the contributions of women artists and their work, which in fact has both elevated and complicated our understanding of modern art and abstraction over the last century.

Our understanding around ideas about abstraction, spirituality and magic, for example, have recently be- gun to shift as we learn of the contributions of artists such as Hilma af Klimt, Agnes Pelton and Emma Kunz. Each in their own way they sought to give light to the mystical sources and inspirations that gave ÔÇ£formÔÇØ to otherwise intangible concepts ÔÇô ideas not found in nature but that live in the imagination. Interests in non-western religions and theosophy led many of these artists to seek knowledge from leading figures such as the Russian e╠ümigre╠ü Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy1 , and Annie Besant, author of the influential book Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation (1901), that sought to visualize thoughts, experiences, emotions and music. Simultaneous to these formal explorations were investigations into materials and craft that were first instigated by the legendary figure Annie Albers who was forced to work in the weaving studio at the Bauhaus because it was the only area open to women. Later she would say, ÔÇ£In my case it was threads that caught me, really against my will. To work with threads seemed sissy to me. I wanted something to be conquered. But circumstances held me to threads and they won me over.ÔÇØ2 Gunta Sto╠êlzl (5 March 1897 ÔÇô 22 April 1983), the head of the Bauhaus weaving workshop where Albers studied, emphasized the singular nature of the woven form, at once a platform for the investigation of form, color, texture and material specific to weaving and an opportunity for the woven object to lay claim to itself as a modernist medium.

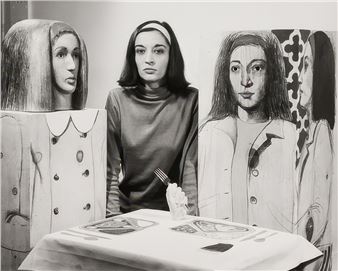

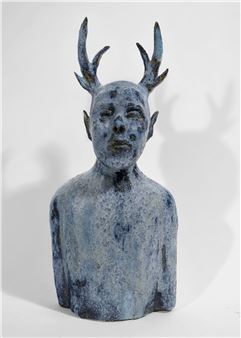

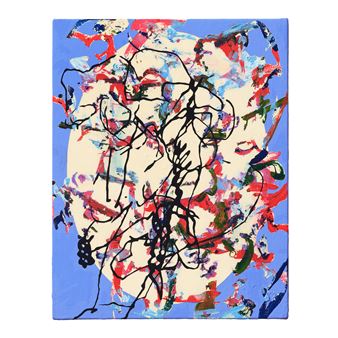

ARTISTS

ARTISTS